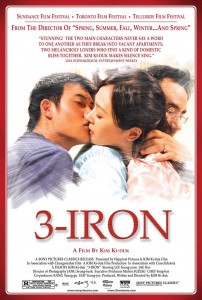

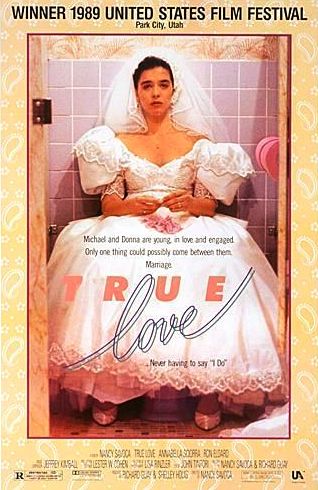

SPRING SUMMER FALL WINTER… AND SPRING

“Go and find all the animals and release them from the stones. Then I will release you too. But if any of the animals, the fish, the frog or the snake is dead… you will carry the stone in your heart for the rest of your life.” – Master to Protégé

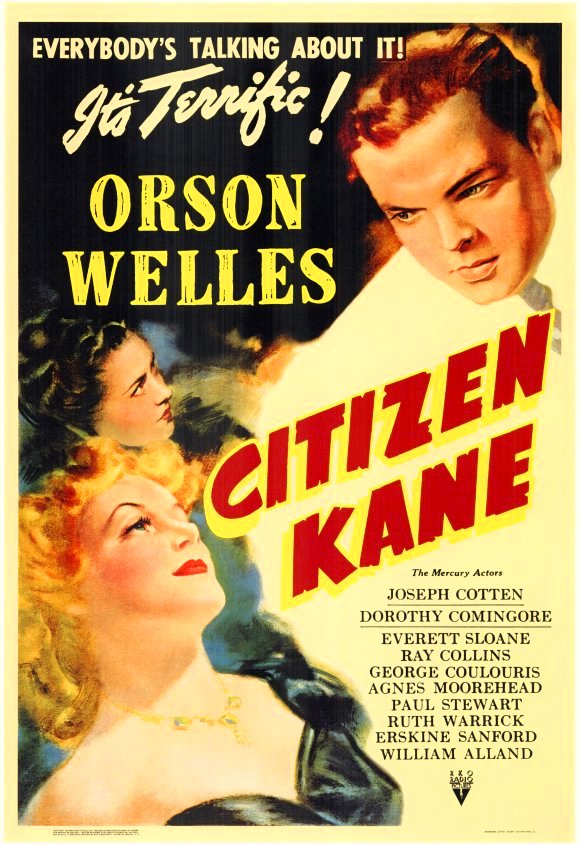

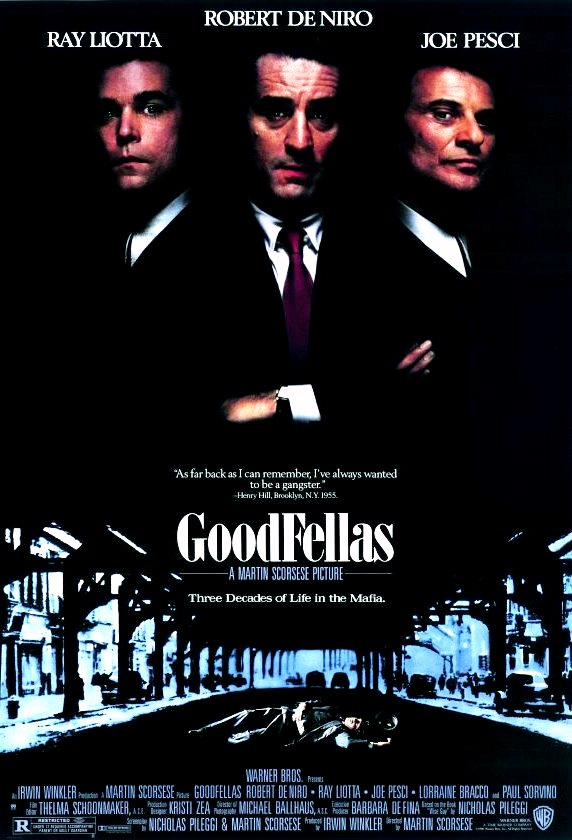

The first time I watched it, I thought, “Wow, this is beautiful. But I don’t think I can last all the way through if there isn’t a story to support it.” Months of contemplation after I saw it, Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring (2003, South Korea) became, for me, the Greatest Film Ever Made. A feat that bumps works by Stanley Kubrick, Martin Scorsese, Orson Welles and the Coen Bros. to runners-up. On my best days, it is a film I can talk about uninterrupted for hours. But only so much can be said in an essay to reach those who are unacquainted (which face it, is almost all of you readers). With those I know, I rhapsodically crave to share conversation over it. I want to discuss it with people who know more than I do, with people that know less than me, and with people who know way less. What’s it about? It’s about nothing less than spiritual birth and the renewal of the human soul.

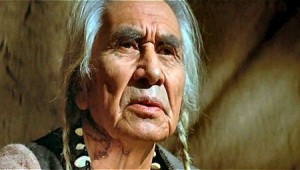

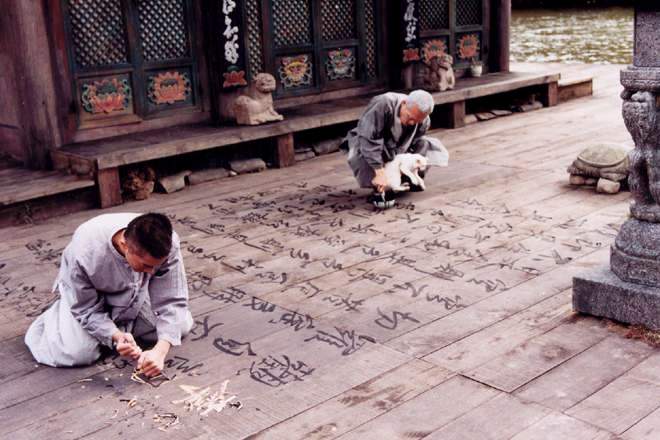

In a beautiful locale that is the epitome of solace, a Buddhist pagoda floats on a lake that is, in every direction seen, removed from civilization. The Master (Yeong-su Oh), who has chosen a life of celibacy and prayer, cares after a young boy (Jong-ho Kim) whom he raises to be a monk like him. Their whole life centers around isolation and prayer – which sounds too inhibiting to the possibilities of a human life until you begin to admire the purity of it. What astounds me, as an aside, is the performance by Yeong-su whom I don’t see as an actor but as a genuine spiritual presence.

All boys demonstrate mischief at one time or another. The boy ties a stone to a fish, a frog and a snake to watch them suffer and giggles while he’s doing it. He awakes the next morning to find a heavy rock on his back, tightly bound, that his master has calculated. Untie the animals is the command. “You will carry the stone in your heart for the rest of your life,” the Master pronounces if the animals are dead. That’s the first 15 minutes of the film.

All boys demonstrate mischief at one time or another. The boy ties a stone to a fish, a frog and a snake to watch them suffer and giggles while he’s doing it. He awakes the next morning to find a heavy rock on his back, tightly bound, that his master has calculated. Untie the animals is the command. “You will carry the stone in your heart for the rest of your life,” the Master pronounces if the animals are dead. That’s the first 15 minutes of the film.

The film leap years ahead with each passage representing a new season. In the summer, we see the boy has now become a young monk (Seo Jae-kyung). The master and monk welcome the arrival of a mother (Kim Jung-young) and her young teenage girl (Ha Yeo-jin) who is sick, although we never learn what her illness is. It could be many things, and because there is no bodily damage or sign of cancer, we can assume that this is a spiritual sickness that stems from trauma.

The young protégé and girl like each other. Celibacy is broken, and the film is not shy about sex. But observe with wonder – here’s a boy who has discovered sex naturally without the aid of pornography, the jade of social media, the influence of puerile schoolboys. I envy how sex is discovered naturally as well as absolutely. Sex for the girl feels positive as well. It is implied to be a cure for whatever she is going through.

The young protégé and girl like each other. Celibacy is broken, and the film is not shy about sex. But observe with wonder – here’s a boy who has discovered sex naturally without the aid of pornography, the jade of social media, the influence of puerile schoolboys. I envy how sex is discovered naturally as well as absolutely. Sex for the girl feels positive as well. It is implied to be a cure for whatever she is going through.

Up until now, we observe change in attitudes of a young man in reconsidering his devout life. We have observed daily rituals and then we see broken rituals, moments of the boy rebelling. We witness the faults of the young boy and then the transgressions of him later as a young man. We witness the joys of sex, the clarity of solitude, and the disconnect of those two that cause inner conflict. To explain practically: I sometimes want something else from my life, but then destiny kicks in and urges me to continue with my life’s work. I had wished to alter my identity, but destiny has already been decided.

I have sometimes acted out in fury in my lifetime as well, and have struggled to return to my calm center. The young boy deserts his master and upbringing, leaving for a decade. He returns as a grown-up (now played by Young Min-Kim) who is possessed by inconsumable rage. What does it really take for a man of anger to return to a calm center? The Fall segment of the film depicts his penance, which calls for humility as well as concentration. Accepting beatings is part of his rehabilitation.

I would find it negligent to not mention yoga for the Winter segment. This discipline is a means to restoration of the pure spiritual practices the character grew up on. New visitors come, a mother and a baby which become a new responsibility. It’s evident that the protégé has now become master because he has accepted this as his identity. He has attained likeness to his Master – whom has passed. And yet something tells us he has reincarnated into the vessel of an animal. It could feel like a throwaway shot but somehow the animal of choice seems to move with purpose, with an acute awareness. I wonder how many shots it required to achieve this.

I would find it negligent to not mention yoga for the Winter segment. This discipline is a means to restoration of the pure spiritual practices the character grew up on. New visitors come, a mother and a baby which become a new responsibility. It’s evident that the protégé has now become master because he has accepted this as his identity. He has attained likeness to his Master – whom has passed. And yet something tells us he has reincarnated into the vessel of an animal. It could feel like a throwaway shot but somehow the animal of choice seems to move with purpose, with an acute awareness. I wonder how many shots it required to achieve this.

The final “…and Spring” is the briefest segment. We have come to witness the circle of life, all in a 95 minute film. The directing is always highly conscious, relevant, and visually strong.

The filmmaker is Kim Ki-Duk who has been lucky enough to make 18 films with hardly one of them pandering to commercialism. In his twenties, he traveled to Paris to become a painter, selling art on the streets. He was not a film aficionado, he attests. But in that year of 1991 he saw three films that made him want to become a filmmaker: “Lovers on the Bridge,” “The Lover” and “The Silence of the Lambs.” When you see Ki-Duk’s films, you will notice many murals in the background which he draws himself. Also the oldest version of the character in “Spring Summer Fall Winter… and Spring” is the only time Ki-Duk has acted in himself.

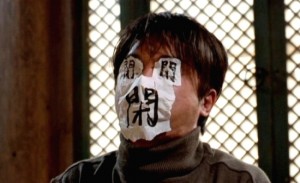

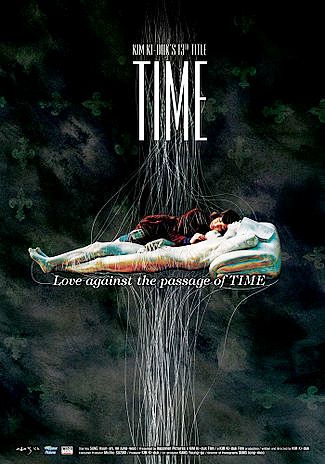

There is a lack of conventionality and formula in Ki-Duk’s films, perhaps because he did not grow up indoctrinated by formula films since he saw so few. Let me list in order my favorite films of his: “3-Iron” (2005) is a beautiful and spiritually deep love story that is also among the very best films ever made; “The Isle” (2000) is a mind-bending allegory on controlling others through sex; “The Bow” (2005) is as upsetting film I’ve seen about the lengths a man will go through to possess a young girl; “Time” (2006) is the most haunting toxic relationship movie I’ve seen – it almost cuts too close to the bone.

There is a lack of conventionality and formula in Ki-Duk’s films, perhaps because he did not grow up indoctrinated by formula films since he saw so few. Let me list in order my favorite films of his: “3-Iron” (2005) is a beautiful and spiritually deep love story that is also among the very best films ever made; “The Isle” (2000) is a mind-bending allegory on controlling others through sex; “The Bow” (2005) is as upsetting film I’ve seen about the lengths a man will go through to possess a young girl; “Time” (2006) is the most haunting toxic relationship movie I’ve seen – it almost cuts too close to the bone.

Ki-Duk’s other films are equally uncompromising. “Samaritan Girl” (2004) contains audacious material of a teen needlessly prostituting herself when she has a caring father and a decent middle class home; “Address Unknown” (2001) is one of the most despairing movies I’ve ever seen, examining Korean citizen poverty set in a region outside of a U.S. army base; “Birdcage Inn” (1998) about a family so poor they send their daughter to school by day and prostitute her at night; “The Coast Guard” (2002) is of a soldier’s guilt after the accidental killing of a local citizen, an interesting and worthy drama until the protagonist becomes a symbolic abstraction. Accumulatively, and overall, these films have changed what I’m looking for when I watch film.

Kim Ki-Duk’s euphoric film is to be carried with you in your heart and mind, day to day, for now and for the future, from birth to old age. Mesmerizing is not a word I’ve used often. I had trouble writing this essay because my eyes are glued to the screen. To get the words printed here I’d have to put it on pause even though I’ve seen it ten times already. With no sound on, it still transports me into a realm of altered states.

Kim Ki-Duk’s euphoric film is to be carried with you in your heart and mind, day to day, for now and for the future, from birth to old age. Mesmerizing is not a word I’ve used often. I had trouble writing this essay because my eyes are glued to the screen. To get the words printed here I’d have to put it on pause even though I’ve seen it ten times already. With no sound on, it still transports me into a realm of altered states.

Click here to read feature on best films of the decade article.

95 Minutes. Rated R.

Film Cousins:

“The Last Temptation of Christ” (1988); “Orlando” (1993); “Chunhyang” (2000, South Korea); “Waking Life” (2001); “3-Iron” (2005, South Korea); “The Master” (2012).

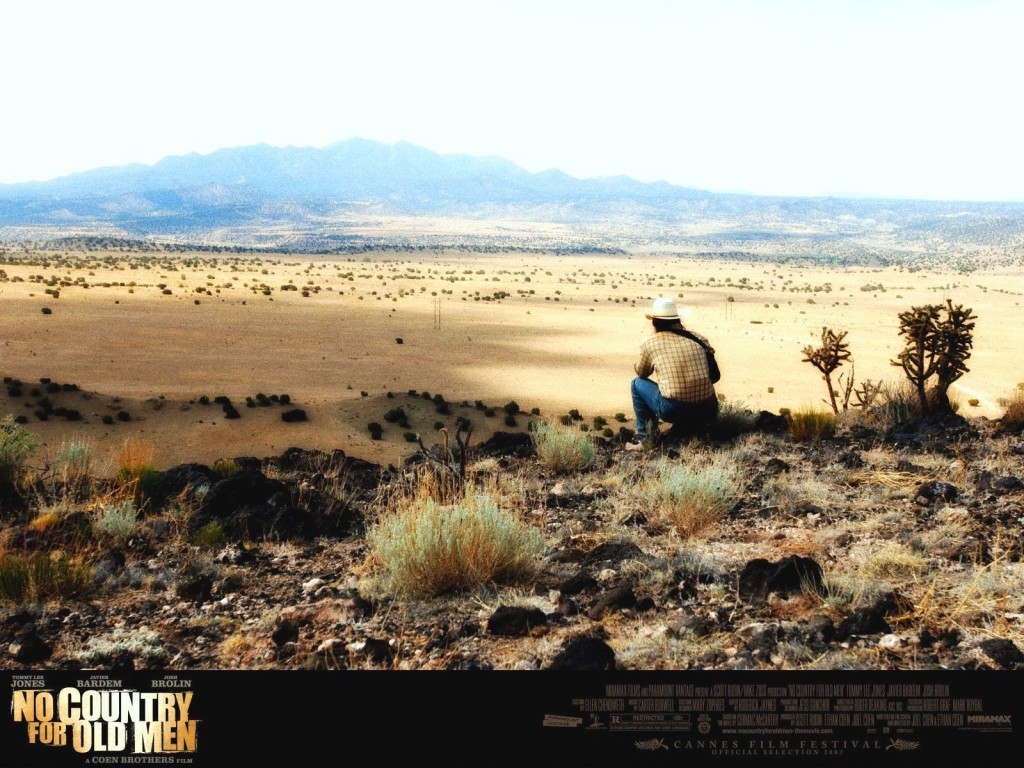

ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST

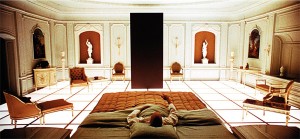

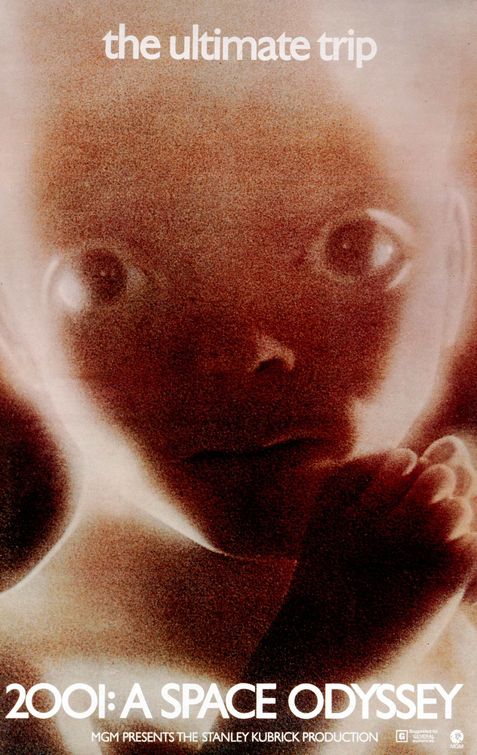

Sergio Leone often goes for pure visual storytelling without dialogue, but everything indeed is a sophisticated puzzle piece. At the time in 1969, Once Upon a Time in the West was thought of as an overblown western with a thin plot if you could believe it. Possibly thought of as thin only because the first hour sets up mood and scant circumstance instead of hurling expository plot information at us all at once; we’re clouded in mystery as to the characters’ wants but it is parceled out prudently. Patience, people, patience! The people who complained are likely the same people that complained during “2001: A Space Odyssey” that there was too much Blue Danube music and not enough explanation going on.

In the shortest summary, Henry Fonda is wickedly unparalleled in the bad guy role, Charles Bronson is the laconic hero seeking obscure revenge, and Claudia Cardinale is the beauty just trying to stake a reasonable life that’s worth living. But, let’s come now, just how infinitely superior is Once Upon a Time in the West over virtually every other western?

After decades of westerns that had characters with cliched goals and short sights on life, here came Sergio Leone’s spellbinding epic with characters who had dreams and vision.

The McBain family is slaughtered in the opening section of the film, leaving Jill (Cardinale) a widow. Turns out the McCain land is preferred real estate; a train depot is to be built for the incoming railroad. There is something of a frozen in time shot later on when the railroad baron Morton (Gabriele Ferzetti) stares at a coastal painting and hears the ocean waves. We know he wants that train depot, that land to himself, and to retire serenely on the California coast on land removed from any potential violence.

Yet Morton hires the very violent and implacable Frank (Fonda) to do some dirty work so he can scoop up land unchallenged. Meanwhile, Bandit Cheyenne (Jason Robards) has been falsely accused of the McCain family massacre and wants to clear his name.

But everybody, even if desires are held close to the chest, wants something life-changing, something consummate in their end goal. Once Upon a Time in the West is a story larger than virtually all, told on Sergio Leone’s ever-widening canvas, to the point it makes others look like child’s play. It is fully awake art that knows what’s really at stake in the world.

This had followed Sergio Leone’s own “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” which came at the time in 1969 when an entirely new rhythm was being created by Leone, with tastes of the spaghetti western and epic form and elegy and pipe dream all coalescing together, that squashed all those one-note westerns that came before. These manifold elements are all lofted by Ennio Morricone’s music, based initially on Bronson’s harmonica, and transfigured into a rapturous and sublime main theme that is enlightened and swelling and beautiful.

Only three westerns ever made, to me, are worthy of being referred to as spellbinding. If you’re asking me, this was the first spellbinding western that had come, and it paved the way for more divergent storytelling in the 1970’s.

165 Minutes. Unrated.

WESTERN / ADULT ORIENTATION / MASTERPIECE VIEWING

Film Cousins: “A Fistful of Dollars” (1964); “Duck, You Sucker!” (1971); “McCabe & Mrs. Miller” (1971); “Once Upon a Time in America” (1984).

THE BALLAD OF NARAYAMA

“I am interested in the relationship of the lower part of the human body and the lower part of the social structure on which the reality of daily Japanese life obstinately supports itself.” — director Shohei Imamura

A despairing masterpiece, but with a keenness for sociology one watches with morbid fascination. The Ballad of Narayama (1983, Japan) appears to be a roughhewn but tranquil depiction of nineteenth century life in the mountains of Japan where families adhere to duties to keep the community functioning, only for the film soon to reveal its shocking scenario: When an elder reaches the age of 70 in this oft-famine stricken village, their oldest son is to carry their parent to the top of the mountain in winter and abandon them until they die, as an appeasement to the gods, with the hope that a generous harvest returns to them in the spring.

No one vocally objects to this tradition. If there is complaint of any kind, it is done quietly and away from others. Everybody in the village knows each other’s business, so it’s in every person’s best interest to not stir up dissension. The social rules of this clan have been going on for hundreds of years, and to not be in outcast, every person is best off to stay in line.

I have just seen the movie for the second time after it has been about fifteen years the first time I saw it. I was stunned by the graphic sexual nature of the film, I could not believe I did not remember it being that way. In the film, only the first-born living sons are allowed to marry and take a wife while all secondary sons are supposed to toil and support the family. There is an astonishing sneaking around by all the younger siblings with other women in the village, all surreptitiously. To me, there seems to be a lot of sexual repression in this society – and then desires blow in spurts, and men and women run off into the woods or in the dark of night to conduct their “secret” affairs.

There is one disliked middle-aged man in the village who is known as a virgin (also known as “stinky”) and he gets to the point he will do anything for a woman. He has the means to threaten the community that he is going to ruin the food supply if he doesn’t get a woman, and so one woman has to be chosen to submit. The younger women refuse, and one of the older woman chooses to appease him. The scene has her feeling unpleasant during the act, but does it in surrender for all. A handful of the other men in the village can beg for sex as if they are begging for mercy.

The two main characters are Tatsuhei (Ken Ogata) and Orin (Sumiko Sakamoto), the son and a mother who is 69 and proud to be on the eve of submitting to ubasute, the word for dying in the mountains. Tatsuhei is a strapping built son who has lost interest in sex and lust, and is simply compelled to keep his family healthy and well. Orin is both a wise mother who we trust in large part kept this village running most of her life, and yet her devotion to old rituals suggests zealotry. Orin bashes her front teeth out deliberately so she can inform the others that she is decaying anyway and that her time is coming – as if it will soften the blow to the sons who will miss her.

In one scene, a thief and wife have been caught with a large stolen batch of potatoes that they planned to ration amongst themselves for several seasons. It’s enough to feed a village for a month. The punishment for the two is death, and the sentence is played out immediately and brutally (it’s not a way anybody would want to die). It doesn’t end there. There is discussion the next day by the decision-makers of the villagers that all blood relatives should be executed as well. That means the thief’s daughters shall be brought to termination, too. The husbands to the thief’s daughters are quick to object, but being loud in their protests will not get them anywhere.

The film’s final section is a prolonged journey to Narayama. Tatsuhei is strong enough to carry his mother up some very rugged terrain that is both gorgeous and forbidding. The abandonment site turns out to be completely out of the normal, at least out of the kind of normal you’re used to seeing. With its jumble of skeleton bones and marauding flock of black crows, it is certainly a death camp but one where each person dies solo. Tatsuhei does not want to let go of his mother and showers her with praise. He wants confirmation from her. She wants to die with dignity and for her son to return home with not sobs of regrets but with dignity. We do see in the film another son who carries a father who does not want to die with dignity. Orin, however, seems to know what it is expected of her. Tatsuhei questions the tradition, but Orin prefers him not to speak.

The film’s final section is a prolonged journey to Narayama. Tatsuhei is strong enough to carry his mother up some very rugged terrain that is both gorgeous and forbidding. The abandonment site turns out to be completely out of the normal, at least out of the kind of normal you’re used to seeing. With its jumble of skeleton bones and marauding flock of black crows, it is certainly a death camp but one where each person dies solo. Tatsuhei does not want to let go of his mother and showers her with praise. He wants confirmation from her. She wants to die with dignity and for her son to return home with not sobs of regrets but with dignity. We do see in the film another son who carries a father who does not want to die with dignity. Orin, however, seems to know what it is expected of her. Tatsuhei questions the tradition, but Orin prefers him not to speak.

You finish the film and wonder: how many more decades would go until this clan decides their draconian rituals are unnecessary?

Cannes Film Festival Palm D’Or winner in 1983. Director Shohei Imamura’s other great film is 1979’s “Vengeance is Mine,” about contemporary Japan’s most infamous serial killer.

129 Minutes. Rated NR. Japanese with English subtitles.

HISTORICAL DRAMA / ADULT ORIENTATION / MASTERPIECE

Film Cousins: “Ikiru” (1952, Japan); “The Ballad of Narayama” (1958, Japan); “Vengeance is Mine” (1979, Japan); “Silence” (2016).

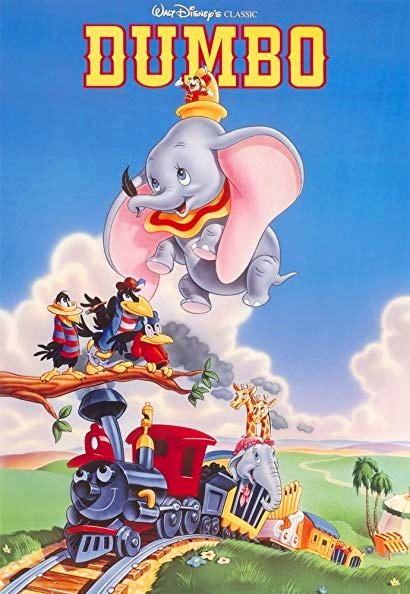

DUMBO

The 1941 Dumbo was the fourth Walt Disney film and a rush job for the studio, it is lean in the storytelling department running at a nimble 64-minutes. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was the first feature from Disney’s studio, in 1937, released to high acclaim and healthy box office. But the over-produced Fantasia and the tepid reception for Pinocchio (unlucky timing as WWII woes kept people from going to the movies that month) prompted Walt Disney to browse closer on the teaser drawings on his desk and push ahead quickly on the elephant at the circus tale in hopes to turn a fast buck, and it did turn fortuitous artistically and commercially.

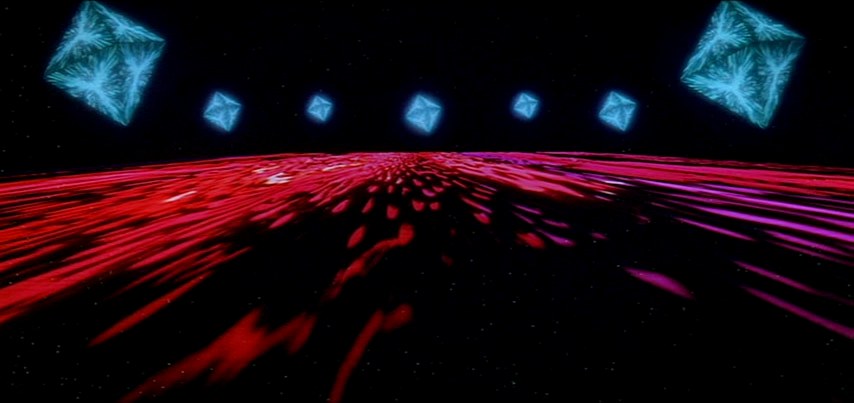

Scored to some rah-rah music and accompanied with a few sparse songs (“Look Out for Mr. Stork,” “Casey Jr.,” “Baby Mine”), it strings along starting simply with a traveling circus by train that’s right out of Watty Piper’s children’s book “The Little Engine That Could,” then the arrival of Dumbo to Mrs. Jumbo by Stork, some lack of self-confidence by the titular pachyderm whose long face and oversized ears makes for some easy pathos, some hapless circus incidents, some heartrending mother and child separation enforced by the capitalist clueless, a team-up with Timothy the Mouse and later some gabby African-American crows, and a six-minute champagne-high “Pink Elephants on Parade” sequence that is the most avante-garde animating of its kind until 1968’s “Yellow Submarine” went full experimental. Dumbo acquires a singular talent by the end to wreak revenge on his tormentors by virtue of his big ears, and as far as emotional powerhouses go, this early Disney favorite of mine just crushes it.

The 2019 remake has Tim Burton flourishes, is regrettably over-produced, diluted by too many cutaways to human characters.

64 Minutes. Rated G.

FAMILY FILM / LIFE LESSONS / WEEKEND FAMILY MOVIE AND DINNER

Film Cousins: “Pinocchio” (1940); “The Jungle Book” (1967); “Larger Than Life” (1996); “Dumbo” (2019).

THE PRIZE WINNER OF DEFIANCE, OHIO

“It wasn’t even my best one!” – Evelyn

Up until now, “The Tree of Life” and “Far From Heaven” have long been for me the two best films about 1950’s life. The Prize Winner of Defiance, Ohio (2005), a completely overlooked gem with Julianne Moore as a stay at home mother who feeds her family of ten by winning contests, needs to join the company. When I was young I was vaguely aware of a past era when people won prizes from home by supplying commercial slogans and jingles for big companies (today, you have to go on a game show). Based on a memoir, the story here is an ebullient reverie of that time.

Moore is phenomenal once again (1950’s roles suit her) as the almost always unflappable mother who can change diapers, give kids baths, cook meals and negotiate payments with the milk man – all seemingly at once. She is bogged down by her husband played by Woody Harrelson who calls her at all times “mother,” not wife. For a few moments it is a quirky sight to see him throwing a fit over a Red Sox game that he hears on the radio. Then the tone emboldens, and we gather how his temperamental six-year old rages have silted the family. Harrelson, as this denial alcoholic, gives another great underrated performance. Who enables his drinking habit, by the way? The local cops and the priest who too easily side with him on his revere for the Red Sox.

“Defiance, Ohio” is a comedy-drama of highs and lows, and it deftly blends the comedy with the harsher moments. Moore’s character Evelyn Ryan wins deep freezers, trips, cars, bird feeders, pogo sticks, supermarket sweeps and cash prizes which are necessary to pay her mortgage since the hubby drinks away his paychecks. Evelyn does this all from home, and she never leaves her home, we realize.

Several years into the story she gets an invite to travel some ninety miles to visit a “rival” contester (played by Laura Dern), who has become a pen pal, to meet her and all her friends. Conventional wisdom is that this pushy Dern character wants to meet Evelyn so she can steal all of her ideas, and that Evelyn is all too willing to go let her guard down because she’s lonely. That’s also conventional movie plotting, but the movie had another thing coming for me. Instead, it’s a snapshot of 1950’s housewives coming together in sorority.

Harrelson’s “father” is all too quick-triggered for jealousy, and he’s a far more trickier case of reproach than Dennis Quaid’s character in “Far From Heaven” or Brad Pitt in “The Tree of Life.” Evelyn Rose is quite an ordinary 1950’s archetype in a way, but she’s required in many poignant ways to save her family and keep them afloat. I was amazed by how much I enjoyed “The Prize Winner of Defiance, Ohio.” Embrace the title.

Directed by Jane Anderson (writer of “The Positively True Adventures of the Alleged Texas Cheerleader-Murdering Mom”) with a peerless insight into the past, and the memoir was written by Evelyn’s daughter Terry Ryan.

99 Minutes. Rated PG-13.

PERIOD DRAMA / THINKING TEENS / SPRING AWAKENING

Film Cousins: “Desert Bloom” (1986); “Far From Heaven” (2002); “The Tree of Life” (2011); “Carol” (2015).

BLADE RUNNER

“It’s too bad she won’t live. But then again, who does?”

One of the seminal works of out-there, mind-blowing science fiction. Blade Runner (1982), so complex, is suddenly more simple after its new complicated sequel has arrived. All jokey comparisons aside, the original remains challenging, perplexing and often profound, and its themes on dehumanization are stronger. Yes, the sequel shares these potent qualities and certainly is a deep follow-up, but somehow you just love an original that set the groundwork. At the time, its’ use of an origami unicorn was a head-spinning device of symbolism, making you refigure the entire film in your head. Of course, I’m speaking of the later director’s cut. I have loved the original 1982 studio release which had an admittedly different softened ending, the 1990’s director’s cut, the 2007 final director’s cut, then there are the international cuts that took place in the 1980’s – did Ridley Scott get obsessed with tinkering with his film, or what? He spent years tightening the screws on his masterpiece.

Harrison Ford played it cold as a blade runner of the 2019 future assigned to hunt down unauthorized androids, in what was a misbegotten Earth riddled with pollution and obscenely cluttered technology. He hunts one replicant, then another, then finds the remaining ones pairing up to take him down (Rutger Hauer, Daryl Hannah). Hauer as the android Roy has a concluding monologue that is among cinema’s most poetic speeches about what it means to live a vast life. Deckard gets the message, and has empathy for his kind.

There were always questions regarding the film though, like, why not assign a team of blade runners? Why is it just one blade runner doing all this dirty work? One could say its’ one of the staples of film noir to have one loner hero. Or you could develop a number of conspiracy theories about why it’s just Ford’s Deckard. Nobody wants a trace of these android terminations, and Deckard is understated enough do the work and keep to himself.

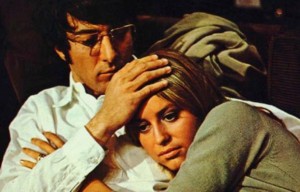

Then why the infatuation with Rachel (Sean Young)? He’s suddenly hot-blooded for her because she appears as a desirable 1940’s pin-up. It is revealed quite early that she is a replicant, and that she doesn’t know that she is one. She encompasses true human feelings. When Deckard engages in a wet, sultry kiss he’s turned on. She’s just a replicant, but she’s better than a real woman. Rachel is not real, but she’s far more beautiful, elegant and sultry then what else is left there. Real women of Los Angeles 2019 are trash.

The key to “Blade Runner” are the mentions of the off-world colonies which somehow fill your mind that those desired places are better habitats than the ruined Earth. Once you start making deductions, the humans remaining on Earth are outcasts and undesirables – they are failed applicants to make their way off Earth. Many of them, you must take notice have diseases or deficiencies, and so are stuck on Earth.

So why doesn’t Deckard ever consider leaving the planet, or even Los Angeles? The haunting part of the character is that he doesn’t have the ambition to, that he’s brainwashed to stay. But the unicorn at the end says a lot about his brain

117 Minutes on the Final Director’s Cut. Rated R.

SCIENCE FICTION / THINKING MAN’S THRILLER / MASTERPIECE VIEWING

Film Cousins: “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968); “A.I.” (2001); “Minority Report” (2002); “Blade Runner 2049” (2017).

PARIS, TEXAS

The drifter walks through hot, dry plains who would seem to belong to no one and have nothing. That would be Harry Dean Stanton as Travis, walking endlessly with no final destination in Paris, Texas (1984). He has been wandering in the wilderness for four years wearing his raggedy mud-stained suit and baseball cap. It’s easy to assume that he is crazy, but then we get to know his character and know that he had a past. He has been walking the desert as his penance.

A family member gets a tip about Travis’ whereabouts. Dean Stockwell, as the brother Walt, flies in from Los Angeles to pick up his vagrant brother whom he thought dead. Annoyed with the silence, Walt riles him to cut the crap and say something. Travis has a mournful tone when he does finally decide to speak. Though he mumbles at first, Travis’ obsession has something about how he destroyed his marriage out of jealousy and rage, besieged with nasty alcoholism. Travis was once joyously in love with Jane (Nastassja Kinski), a damn fine looker. He also left his four-year old son Hunter behind.

Upon their arrival in Los Angeles, Travis is reunited him with his young son (Hunter Carson) whom has been watched over by Walt, now in elementary school. Travis is greeted warmly by Walt’s wife Anne (Aurore Clement) wd iwho is generously hospitable on one hand, but guarded with a need to protect Hunter’s interests. Hunter is at first confused by the presence of Travis, treating him like a stranger. Travis learns that Jane wires money to Hunter on a monthly basis even though she makes no other contact with him. The bank wire comes from Houston, Texas, where Travis he now must go.

It is unclear what Travis’ intentions are at first, whether he wants to make amends with his wife or attempt to reunite with her for good. Travis lets Hunter tag-along with him without getting permission from Walt and Anne, whom were Hunter’s substitute parents for years.

“Paris, Texas” is a film of deep anguish and great sorrow, because we learn that Travis’ past destructive ways drove his wife to an unsavory type of lifestyle working in a glass booth at a sex club. Jane sits behind a one-side glass in a private booth where she does phone sex (and peep shows) to customers over a telephone. The customers can see her but she cannot see them.

“These two people. They were in love with each other. The girl was very young, about 17 or 18, I guess. And the guy was quite a bit older. He was kind of raggedy and wild. And she was very beautiful, you know?” Travis blathers away. There’s a tough scene where Travis with humility admits to his son Hunter, who isn’t old enough to understand all the implications, that Travis abused his mother. Travis does what he can to reconcile a mother and son, putting them above himself. In this process, we come to learn how past wounds came to destroy Jane’s self-worth.

I certainly feel this is a superb film, one told at great length and with deliberate pacing – it has the sprawl, observation and nuance of great fiction that is punctuated by a pitch-perfect Stanton performance. It takes its time to get intimate with its compelling range of characters and gets us to know the history behind them, letting us discover their secrets and pained wishes in the process. Director Wim Wenders, a German who made a transition into making American films briefly, is known for a few cult film obscurities but this is to me his finest film (I’d rank it the second best film of 1984, just under “Amadeus”). Robby Muller’s vast widescreen cinematography is essential to its artistic success and Ry Cooder’s moody string-guitar music score evokes a sense of distance and remoteness. Stanton and screenwriter Sam Shepard sadly passed away a few months between each other in 2017.

150 Minutes. Rated R.

DRAMA / ADULT ORIENTATION / MASTERPIECE VIEWING

Film Cousins: “sex, lies and videotape” (1989); “Man Push Cart” (2006); “Goodbye Solo” (2008); “Manchester by the Sea” (2016).

THE BAND WAGON

“She was scared. Scared as a turkey in November.” – Tony Hunter

“Singin’ in the Rain” is supposed to be my all-time favorite musical, and everybody else says it too, but after awhile I knew it by heart so well I was happy to stumble upon a new favorite. The Band Wagon (1953) a dozen viewings later is something of a miracle to me in which I never cease to find something else to delight in. Fred Astaire starred in it just before he was sliding into the twilight of his career, and he happened to play a fallen star named Tony Hunter, a one-time matinee idol and hoofer (that’s a tap-dance man), who has hit a brick wall in his career and goes to Broadway to revitalize himself. Just as 1952’s “Singin’ in the Rain” was a backstage musical comedy about Hollywood, 1953’s “The Band Wagon” was a backstage musical comedy about Broadway. They happen to be from the same writers, Betty Comdon and Adolph Green.

It wasn’t “Singin’s” Stanley Donen but Vincente Minnelli directed this one, coming off the heels of his Oscar-winning “An American in Paris,” but while that one had exquisite numbers it was pageant overkill, his work is more cool and spry here. An example would be “Shine On Your Shoes,” the first musical number where Tony Hunter, flummoxed for being out of work, dances his troubles away at a penny arcade, and memorably squares off with a black shoeshine man – and some perplexed onlookers. The scene is jolly in the way he engages with some of the carnival games while he does his shimmy at the same time.

With the help of some friends (Nanette Fabray, Oscar Levant – she spat on his awful prima donna behavior in real life), Tony enlists the services of Jeffrey Cordova (Jack Buchanon), a jack of all trades Orson Welles type with ginormous ego intact, to be the director of his next would-be Broadway hit. Cyd Charisse is a dream of a ballet dancer who is brought in to be Tony’s co-star, and before there is love there is competitive jealousy. But the hiccup is that this musical project turns into Cordova’s update of Faust, alas, a pretentious mess. On the rebound, Tony rallies everybody to bounce back with a musical revue. Sounds like the plot of any given “Muppets” movie that would happen years later, but it is well-worn plot of many years before this too. Just the same, only better.

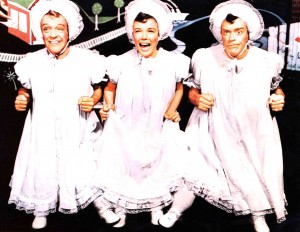

Romance is personified in the “Dancing in the Dark” number set in an idealized Central Park. You will take great notice in the carriage ride that employs subtle black & white back projection that gives it a misty look, then the costumes (Charisse’s fit-and-flair cost $1,000 to make), then the actual dancing which is as enchanting and pitch-perfect as they come. After the Faustian debacle, the subsequent musical show numbers are a hoot, and particularly I get giddy over the bizarre “Triplets” which has Astaire, Cordova, and Fabray all appearing as midgets dressed as babies. Actually, they were dancing on their knees while strap-on artificial legs dangled before them. This required many takes because at least one of them would have trouble not falling over.

Romance is personified in the “Dancing in the Dark” number set in an idealized Central Park. You will take great notice in the carriage ride that employs subtle black & white back projection that gives it a misty look, then the costumes (Charisse’s fit-and-flair cost $1,000 to make), then the actual dancing which is as enchanting and pitch-perfect as they come. After the Faustian debacle, the subsequent musical show numbers are a hoot, and particularly I get giddy over the bizarre “Triplets” which has Astaire, Cordova, and Fabray all appearing as midgets dressed as babies. Actually, they were dancing on their knees while strap-on artificial legs dangled before them. This required many takes because at least one of them would have trouble not falling over.

But has there ever been a musical sequence as avante-garde as the climactic “Girl Hunt?” This prolonged and elaborate number contains phantasmagoric lighting, exaggeratingly baroque sets, glittering costumes, surreal play-acting on jazz and noir themes, and flat-out audacity. Ultimately, it epitomizes the kind of old Hollywood elegance that is out of commission in today’s times. Alright, there was one before it even more audacious: the centerpiece ballet number in 1948’s “The Red Shoes” by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger.

What you also don’t find today, outside of tentpole Disney films, is this kind of unabashed corniness which is demonstrated all too blatantly especially in the final “That’s Entertainment!” scene (the now ubiquitous song was written for this film). There’s a glee to “The Band Wagon” though, that says, all of our old clichéd ideas works just as fabulous as the new avante-garde experiments – nobody among them is going to apologize for entertaining the pants off you. “Singin’ in the Rain” will always remain as the signature representation of what classic Hollywood was, and truly it is a godsend, but “The Band Wagon” – well, these days I can’t get enough of it, even the stuff in it that’s old hat.

112 Minutes. Unrated.

MUSICAL COMEDY / ALL AGES / MASTERPIECE VIEWING

Film Cousins: “Easter Parade” (1948); “An American in Paris” (1951); “Singin’ in the Rain” (1952); “Funny Face” (1957).

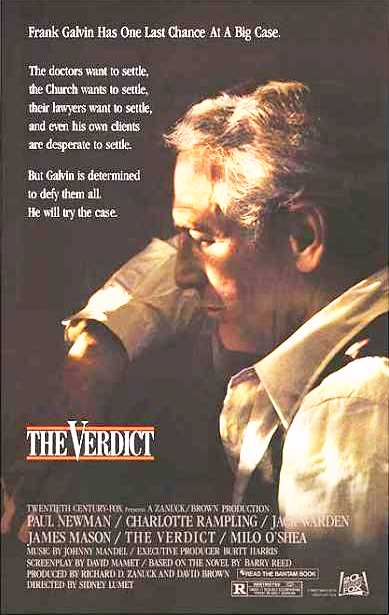

THE VERDICT

“If I take the money I’m lost. I’ll just be a rich ambulance chaser.” – Frank Galvin

Read it here, this is the all-time best courtroom drama ever made. The Verdict (1982) is from the autumn part of Paul Newman’s career after he had distinguished himself as one of Hollywood’s most bankable stars. He was allowed, and game at this point in his career, to play damaged characters. The film, by director Sidney Lumet (“Network,” “Dog Day Afternoon”), transcends the genre not because it has concocted the mother of all court cases, but because it depicts how the real truth can be neutered by tampered evidence and the human individual discounted within the mechanics of a courtroom.

This is Newman’s finest hour, as a Boston boozehound lawyer Frank Galvin (so croaky he has to grind out his speech) whose track record is so haphazard that he has lost familiarity within a courtroom. An open-and-shut malpractice suit falls into Galvin’s lap, but instead of collecting easy money from a settlement, he wants to fight to win it all. He’s out to prove that negligent doctors at a Catholic hospital carelessly turned a young woman into a vegetable. Galvin more than just wants to win a settlement, he wants to win within a courtroom so that he can test his lawyer skills once again. The clients he represents are furious when they learn he turned down an offer without consulting them.

The opposing defense is headed by snooty lawyer Ed Concannon (James Mason, superb) who is chummy with the judge (Milo O’Shea). More than them, Galvin is up against an over-powerful establishment, the Catholic Church diocese. Once the trial is underway it goes sour in a myriad of ways, one of them is how Galvin asks impertinent questions that drum up favor to the opposing team.

In the midst of this, Newman in one scene punches the lights out on a woman. We who are gentlemen are taught in youth never to strike a woman. The striking of this woman is justified, just see for yourself and you will understand. It could have been the first scene of the film, and everything else could have been flashback, and it would have been an interesting drama deconstructing this event. But oh my God is this shocking moment earned, because she was ever so treacherous with other peoples’ lives at stake. Also powerful is Newman’s final summation speech to the jury and you will see just about the best acting you will ever come across. Only Newman’s Galvin – arrived at the brink of ruin, at the limits of shame, pleading for mercy – could have delivered a speech so soulful, and regardless of any legal outcome, he has at the least, redeemed himself.

Few films have so rigorously downplayed their color palette for stark dramatic effect. This is a triumph for Lumet and Newman in bringing this anguished character study to authentic life, both assisted by a brilliant David Mamet screenplay.

129 Minutes. Rated R.

COURTROOM DRAMA / ADULTS / LATE NIGHT FOOD FOR THOUGHT

Film Cousins: “12 Angry Men” (1957); “The Rainmaker” (1997); “A Civil Action” (1998); “Spotlight” (2015).

UMBERTO D.

“I love humanity, I trust humanity, but humanity has a way of disillusioning me.” — Director Vittorio de Sica

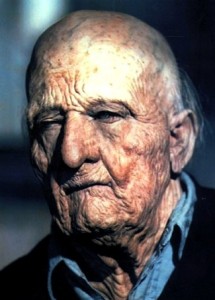

Looks old and crumbly just like the title character, but give it ten minutes and you are drawn into its uncompromising, compassionate gaze. Vittorio De Sica’s Umberto D. (1952, Italy) is as emotionally awakening and touching films you are ever likely to see. It has a persuasive black & white seediness to it, yet the camera is always upfront and direct. Carlo Battisti, in the title role, plays a retired civil servant with an insufficient pension and mounting debt. He dresses with dignity. But perhaps that hides the truth of his dire situation. How quickly this becomes the story of an old man who loses his home, and is booted out onto the streets with only his plucky dog Flike as his companion.

Hanging on the best he can, he scrounges up money. But nobody needs to buy his watch when there are a thousand other watches that can be bought. Umberto’s only friend is a young housekeeper named Maria (Maria Pia Casilio) who is pregnant and destined to be a single mother. She can listen to Umberto’s plans of rummaging up money with a caring heart but she cannot solve his problems. Umberto’s unsympathetic landlady, however, doesn’t really want Umberto to catch up with the back rent. The landlady wants him out so she can spike the cost of the rental. And if there is an ant infestation problem, she would prefer Umberto to be bothered by it.

Inevitably, he loses the place. With no other family or friends to turn to, Umberto has only homelessness ahead of him. But despite his age he has a tough survivalist mentality. He checks into a hospital for an interim, but needs back out to care for his dog Flike who is in other care. Following the hospital dismissal he learns that Flike has been taken by one of the city’s animal shelters with a termination policy. We hold our breath that Umberto can track Flike down in time. The subsequent dog pound scene is rife with tormenting suspense.

If that’s not enough, we reach the gaspingly suspenseful railroad finale with Umberto tucking himself in humbly, hoping his fate goes unnoticed. We have spent time with a man who never bemoaned the cruel social structure that caused his befallen circumstances. We saw him imitate a beggar on the street but couldn’t succumb to the embarrassment. Flike had more luck begging on their behalf.

De Sica was more famous for his previous world class tearjerker “The Bicycle Thief” (1948), which was a distinguishable beginning of the neorealist movement – no formula story, no studio, but a production that hinged on authentic street locations and naturalistic actors. I love that film, too, but I feel in my bones that “Umberto D.” is simply one of the twenty best films ever made. In regards to the casting, Battisti was a 70-year old university lecturer who had never been in a film before, and he is not only immaculate but transcendent of anything peddling for film awards.

Every time I’ve seen it in a theater setting women weep and men gulp in shame. But it goes home with you, to the home of your heart and unforgettably so.

89 Minutes. Unrated.

FOREIGN DRAMA / MATURE TEENS / MASTERPIECE VIEWING

Film Cousins: “The Bicycle Thief” (1948, Italy); “American Heart” (1992); “Wendy and Lucy” (2008); “Time Out of Mind” (2015).

THE ELEPHANT MAN

“It makes me uncomfortable to talk about meanings and things. It’s better not to know so much about what things mean. Because the meaning, it’s a very personal thing, and the meaning for me is different than the meaning for somebody else.”

– David Lynch, director

Supreme filmmaking. The Elephant Man (1980) is a peerless look at 1880’s London, the high society and the low where John Merrick dwelled as a circus freak before being saved, and plays like a window into history. John Hurt is the actor who disappears without a trace under the makeup to play the extremely facially deformed Merrick, said to be the ugliest man who ever lived. Anthony Hopkins brings intelligence and a decent conscience to his role as Doctor Frederick Treves who plucks Merrick from the abusive sideshow.

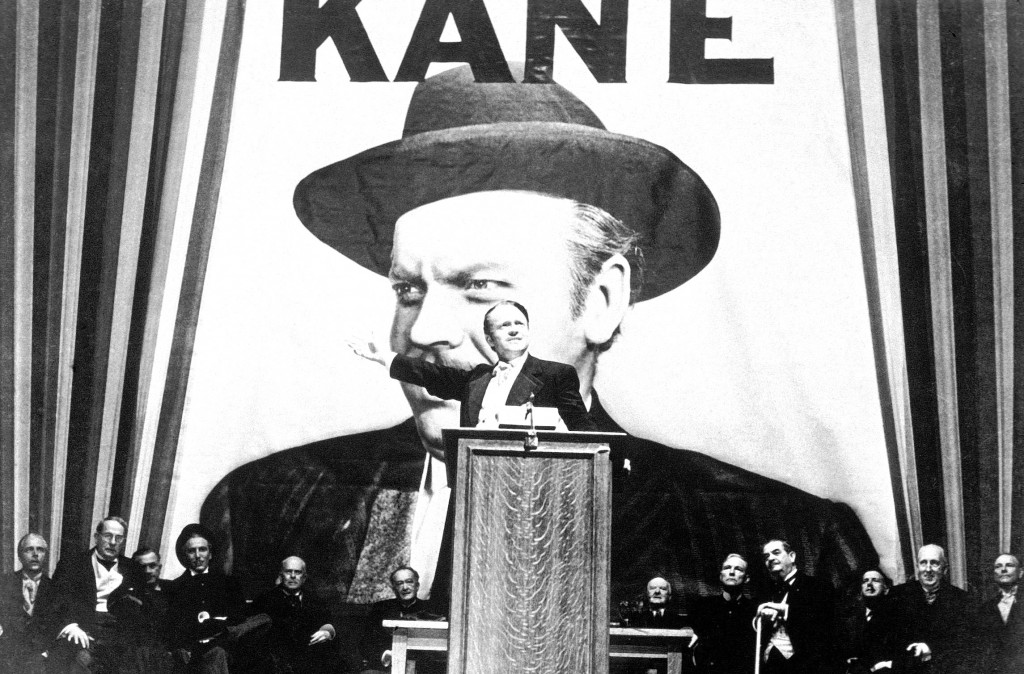

This was David Lynch’s second film – as much a masterpiece as the underground masterpiece “Eraserhead” (1977) he made by raising his own money – and this was his first within a studio system. Artistic passion is evident in every single frame. “The Elephant Man” is perhaps the finest black & white cinematography you will ever see. “Raging Bull” came out the same year, and I think the lighting, shadowing, framing is more accomplished here. I don’t think it’s out of line to say it is as rich and immersive a visual experience as “Citizen Kane,” maybe more.

Freddie Francis is the credited cinematographer, and together with Lynch, they create a foggy gaslights London, old century hospital made of bare elements, hallucinatory dream sequences of industrial age claustrophobia. The opening and closing scenes have been debatable, suggesting a rape of the mother by Merrick by elephants and an apparition drifting into outer space. Lynch has said in interviews that this is surrealism, for he was less interested in fact than he was with inciting gut emotion in his viewers.

What is known by fact is that Merrick was given his own quarters within a hospital care system to be studied, and was trained to elevate his slurs into better speech (the film alludes to this in a minor way). Dr. Treves gives Merrick friends to interact with, but there are doubts of whether letting Merrick mingle with high society gentry is in fact turning him into a different kind of sideshow attraction amongst the rich. Hopkins plays the perceptive doctor as a man burdened with guilt with his own decision-making.

Not everything is grim. There are kind people, too, like theater artist Mrs. Kendal (Anne Bancroft) who befriends him with sobering intentions. There is true love for Merrick there, and delicately implied among a few others, too, left for you to find.

It’s also impossible to deter the inevitable depression of Merrick, being chosen as life’s unlucky one, and Hurt in the role brings a peerless poignancy to his sensitive nature.

This is one of the most emotional experiences of film you can have, but it is indescribable why it is that way. I feel different things while watching it, tapping different relative associations scene to scene. This is a narrative film, that’s actually usual for the very avante-garde David Lynch, but viewing after viewing I still find my responses to it to be a mystery. And I keep pondering over it, with sadness and self-examination all the same. And that cinematography keeps stirring things inside me. There are more than a hundred stupendous images in the film.

Currently, Bradley Cooper is winning raves on Broadway for his lead role in the reprisal for “The Elephant Man,” and has said it was the film that got him interested in acting.

124 Minutes. Rated PG.

DRAMA / ADULT ORIENTATION / LATE NIGHT TEARJERKER

Film Cousins: “The Miracle Worker” (1962); “The Wild Child” (1969, France); “Mask” (1985); “Crumb” (1995).

THE LAST TEMPTATION OF CHRIST

“The dual substance of Christ – the yearning, so human, so superhuman, of man to attain God… has always been a deep inscrutable mystery to me. My principle anguish and source for all my joys and sorrows from my youth onward has been the incessant, merciless battle between the spirit and the flesh… and my soul is the arena where these two armies have clashed and met.”

– Nikos Kazantzakis, author of the book “The Last Temptation of Christ”

This quote arrives in the pre-titles to The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), adapted by Martin Scorsese (“GoodFellas, Raging Bull”) who struggled through most of the 1980’s in order to get it made. It is well-known that Scorsese himself is a lifelong dedicated Italian Catholic who had considered priesthood before he went into filmmaking. When Scorsese found the Kazantzakis novel it was a not a traditional Jesus biopic but instead a unique exploration of the divinity of Jesus. Controversy on the film existed before shooting began. In fact, in 1983 the $20 million dollar production green-lit by Paramount Pictures went into turnaround after right-wing fundamentalist Christian groups conducted an unceasing series of petitions and protests to have it stopped.

Scorsese plundered himself unto other projects, them being “After Hours” (1985) and “The Color of Money” (1986) – terrific, if relatively safe, genre pictures – until he was able to find alternative investors for the film. Universal Pictures agreed to be the financial backers of the film in late 1987 but only contributed to an $8 budget to the film. In 1983, Jesus was to be played by Aidan Quinn and filmed in Israel but was now replaced by Willem Dafoe and filmed in Morocco with a minimalist sparseness on harsh locations.

“The Last Temptation of Christ” respects the Gospels, anybody with intelligence can see that. The final third steers in a controversial new direction, for that’s what offended. If Jesus was more than a deity but a man, then he had to have both wisdom and self-doubt, both strength and fragility. Here’s the touchy part: Scorsese portrays Jesus as a coward and conflicted man before he chooses the right path. This is more compelling to us as not just viewers, but as human beings, to consider Jesus this way instead of as some kind of invincible divinity.

In depiction of his early cowardice, Jesus assists in the crucifixion of a fellow Jew who is guilty of sedition. Rome is a place occupied by hatred and persecution, and its fellowship is comprised of conformists that act upon the word of Pontius Pilate (David Bowie). Jesus is consumed by following society’s orders because he fears the penalty of heresy administered by Rome. He has a calling to go to the desert to await his Father’s message where after forty days he is beckoned to be the Messiah of the people. He does so, but remains conflicted. He wishes he was not the chosen one.

Harvey Keitel as Judas, is the most confrontational of the Apostles and yet the most loyal and confiding to Jesus. Barbara Hershey as Mary Magdalene is a tattoo-adorned prostitute marked by change when she pays witness to the miracles of Jesus, yet there remains skepticism between them – is her son a fraud? The fact that these characterizations are not representations of Sunday school postcards upset conservative groups that want to see Jesus as a perfect sage of wisdom as well as being impervious to pain.

The harrowing crucifixion scene of Jesus is not induced by the hands of Satan but by the hands of Rome. Satan has made several appearances, but the most important time is when he disguises himself in goodness. It’s Satan that tempts to free Jesus from his martyrdom. So here, Kazantzakis and Scorsese (again, controversially) explore a what-if: If Jesus had not died on the cross and become our Savior, it’s likely he would have married and settled with his family. In the film, his temptation is to be an ordinary man.

Of course, Scorsese’s point of the film, the revelation he wants you to see, is if Jesus had not died for his followers that we are able to articulate the depth of importance of what his death meant. But it is recalled that his big monologue scene with Jerusalem burning in the background at the end, the usually ecstatic Scorsese went up to him after the first couple of takes and grumbled, “Is there anything more you can give?” On a subsequent take, Dafoe realizing he was disappointing his director, delivered a magnificent take that found depths of great sorrow and remorse, one that has to be considered one of the great actor moments. Dafoe in the scene and film entire astonishing as the self-tortured Jesus.

Just as powerful as the lead performance is Peter Gabriel’s music, particularly the “It is accomplished” theme. Mournful music as it should be, but somehow it connects emotions of two thousand years ago with how we feel about Jesus dying for our sins today. After genuine filmmaking burrowed in bleakness, Gabriel’s main theme serves as catharsis.

Right-wing fundamentals groups opposed the film after its release in August of 1988. At a Parisian movie theater, there were Molotov cocktails thrown inside the theater which injured thirteen people, four of them permanently left with major burn scars for life. Evangelist Bill Bright offered to buy the prints from Universal so that he could destroy them all permanently. How very Christian of these people!

Scorsese has made more thrilling films to my eyes, but “The Last Temptation of Christ” will always be one of the most important of all films to my soul. It made me wake up and realize that the times of Jesus wasn’t made up of treacly miracles the way my Sunday school books were lamely teaching us. Scorsese makes us comprehend Jesus’ sacrifice was far more significant because choices back then were far more cruel. It would take more than ten years, but “Last Temptation” would change the standards in Hollywood’s Biblical epics.

164 Minutes. Rated R.

DRAMA / LIBERAL MINDS / WEEKEND FOOD FOR THOUGHT

Film Cousins: “The Gospel According to St. Matthew” (1964, Italy); “Kundun” (1997); “Passion of the Christ” (2004); “Exodus: Gods and Kings” (2014).

THE GAMBLER

“$10,000. I probably won’t even need it. I just need to know if I can count on you in case I do.” – Axel

The great film about a gambling junkie and the biggest crime of all is that is doesn’t have a stronger reputation. The Gambler (1974) urgent opening scene has Axel Freed (James Caan) in the hole for $44,000. Axel’s friend Hips (Paul Sorvino), an associate with a bookie, says consolingly he has never seen such a string of bad cards. Axel wants another thousand to bet. Another thousand in order to win back $44,000? Crazy, Hips says. “That’s six El Dorados. $44,000, Axel. It ain’t just numbers!” Axel is a university professor who teaches Dostoevsky, but his income ends there. He has a wealthy family to fall back on supposedly, but he can only dip into that well so many times.

While in debt with bookies Axel is completely aware of what they can do to him. He explains to his mother, “For $10,000 they break your arms. For twenty, your legs. For fifty, you get a whole new face.”

Caan, in the best performance of his career, called this film his favorite. “It’s not easy to make people care about a guy who steals from his mother to pay gambling debts.” Axel doesn’t literally steal from his mother, he asks her for the money. Son escorts his mother to go into the bank together, and afterwards they have one of those long shameful talks about how at this moment this is going to be the end of his gambling. He’s on the way to the bookie, but he’s unavailable. So he takes the $44,000 on him to Vegas with his hot girlfriend (Lauren Hutton) to gamble with. (Now it feels like stealing.) For a few minutes in Vegas, he’s a stud. But a compulsive gambler never knows how to go a week without gambling.

This is a portrait of a man who bets with the excitement of losing, or just barely evading the risks and consequences that come with losing. Addiction to gambling and addiction to the danger of it all is one and the same. He treats his relationship with his lusty girlfriend likewise, he seems to be driven at putting himself in situations of nearly losing her. Both ways for him and her, they don’t seem to have a healthy relationship. They seem to be living in a shallow world where they both get turned on by high drama. If she had any sense, she would quit him.

None of this is played with clichés. The film dodges stereotyping and simple psychology and is instead very uncompromising in portraying tunnel vision. Axel has become a man who ruins any chance of cleaning up his debts when he can. Instead, he has taken that money and parlayed it. As a result, Axel is rounded up by collectors and thrown into a basement to await a punishment from a Mafioso. He is terrified, but even then, he is probably considering how he could throw himself into other danger if he happens to find a way to talk his way out of that one. He does think he’s smart enough to out-negotiate the Mafioso and that he’s gonna get out of there. He certainly has the overstuffed ego to think he will.

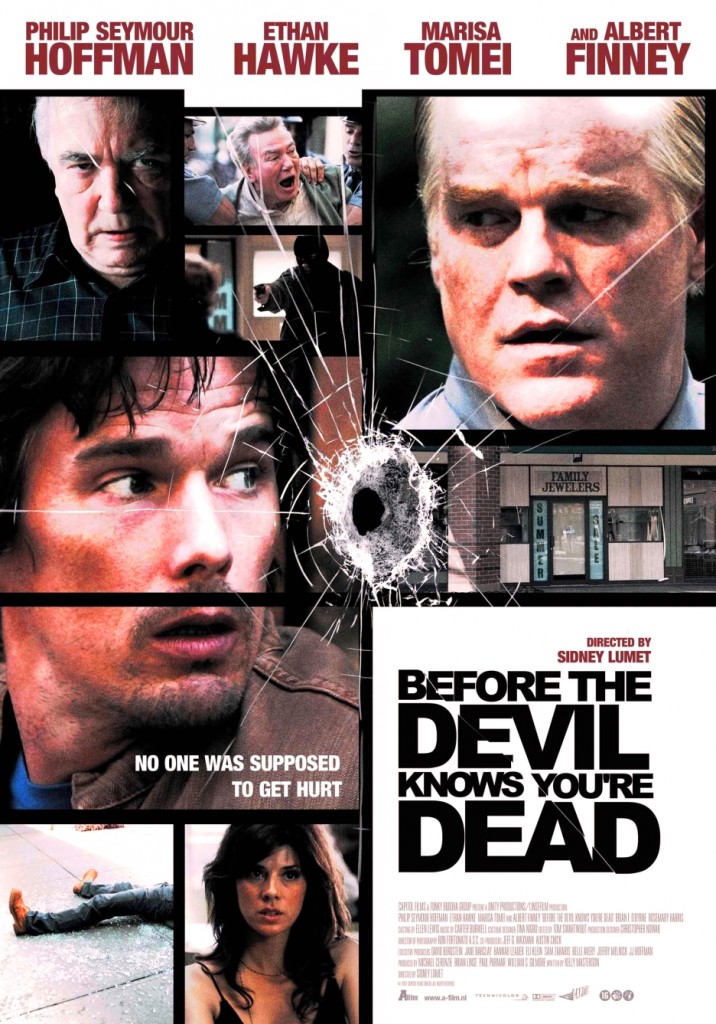

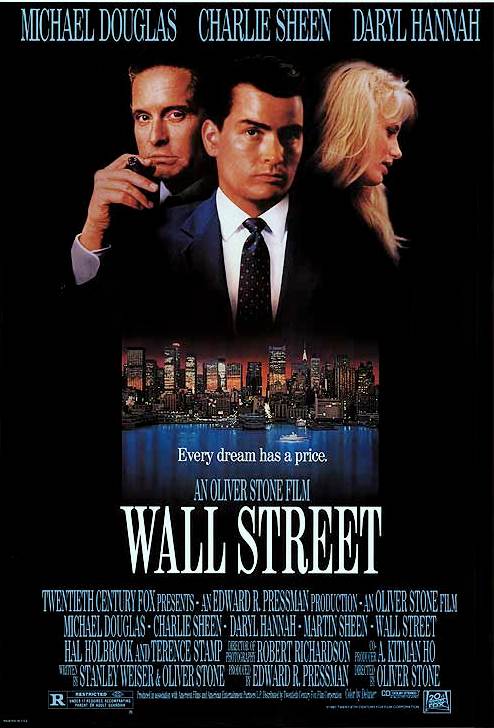

I fear the new remake with Mark Wahlberg, coming out in December 2014, will turn the character’s dark predicaments into an exciting lark. Maybe it will still work as entertainment, but I doubt it will fascinate the way this 1974 film does. In recent years, “Rounders” with Matt Damon and Edward Norton was a guilty pleasure movie about betting your way out of the gutter. “Owning Mahowny” was a much more serious accomplishment of gambling with money one doesn’t have, with Philip Seymour Hoffman in a masterful performance of a schlub who likes the gambling tables and nothing else. What I admire about 1974’s “The Gambler” is that Caan is already a stud trying to be superstud because being anything less is boring. He stops being cognizant of how unreal the high stakes really are.

I fear the new remake with Mark Wahlberg, coming out in December 2014, will turn the character’s dark predicaments into an exciting lark. Maybe it will still work as entertainment, but I doubt it will fascinate the way this 1974 film does. In recent years, “Rounders” with Matt Damon and Edward Norton was a guilty pleasure movie about betting your way out of the gutter. “Owning Mahowny” was a much more serious accomplishment of gambling with money one doesn’t have, with Philip Seymour Hoffman in a masterful performance of a schlub who likes the gambling tables and nothing else. What I admire about 1974’s “The Gambler” is that Caan is already a stud trying to be superstud because being anything less is boring. He stops being cognizant of how unreal the high stakes really are.

The film was written by James Toback (the remarkably gritty crime drama “Fingers” in 1978 became his directorial debut) who says he based it upon personal experiences. Karel Reisz was the director.

111 Minutes. Rated R.

DRAMA / ADDICTION / LATE NIGHT CHILLS

Film Cousins: “The Cincinnati Kid” (1965); “California Split” (1974); “Rounders” (1998); “Owning Mahowny” (2003).

CLOUD ATLAS

“Our lives are not our own. From womb to tomb, we are bound to others. Past and present. And by each crime and every kindness, we birth our future.” — Narrator

“Our lives are not our own. From womb to tomb, we are bound to others. Past and present. And by each crime and every kindness, we birth our future.” — Narrator

I have never been so wrong about a film in my entire life. Viewing Cloud Atlas again I can see why I had some early initial problems that stemmed doubts. There are six stories that range from 1849 to 2346, and God help me that I couldn’t find instant connections and validity between the cross-cutting of them during the first half hour. What co-directors Andy and Lana Wachowski, and Tom Tykwer do, is plant ideas and let them germinate as the episodes develop. Actors Tom Hanks, Halle Berry, Jim Sturges, Hugo Weaving, Hugh Grant and Doona Bae inhabit multiple characters from different strands of time. The more you see the film, and look deeply, the more touching the performances are. Especially of Hanks, who plays weasels, conflicted geniuses, and a wise old man in the far away future who is the embodiment of inner peace.

Yes, and the more you view “Cloud Atlas,” the more you can see the Hanks of 1849, the Hanks of 2012, and the Hanks of 2346 are all the same person. The thematic idea of reincarnation was always there, but it becomes more fitted once you philosophically link the connections. Hanks is an angry soul over time who finds difficulty in finding inner goodness. Sturges is always destined for privilege but campaigns against intolerance time after time, and in frustration of his fragile intellectual soul, he decides to transform into a great physical fighter for his cause. Weaving is evil in every incarnation, and because he loses, he becomes not another human in the far away future scenes, but an evil specter to do his worst harm.

The 2144 scenes in Neo Seoul, Korea are intended to be the most disturbing. This is a portrait of society degenerated to its worst impulses. It is a world of concrete, lit up by artificial colorful holograms. Bae is a clone whose purpose is of a work around the clock server at a vulgar commercial eatery, and she as well as her contemporary clones are given to shortened lifespans. This is a form of slavery that is linked up with other demonstrations of slavery throughout the film, most obviously the 1849 scenes of white masters and slaves. Most comically, Jim Broadbent is a nebbish book publisher named Timothy Cavendish who ends up captive against his will at an old folks’ home. His predicament inspires a comic movie on his life, which is seen by two clones in the future, who begin – to think more expansively about their existence.

I have seen “Cloud Atlas” at least three times now and I still find certain things confusing or baffling. The feral dialect of the far future is not entirely decipherable. But it has not kept me from trying to follow it a little better with each time I see it. I am only vaguely knowing as to why Berry needs to climb a mountain to reset certain power, but I have found other purpose in those scenes, like, the importance is not so much the turn-on of the generator as much as how necessary her appearance is to change Hanks’ destiny. The episode also takes place “106 Years After the Fall,” and is significant for portraying disparate societies rebuilding on Earth following in an unspecific catastrophe that has cut down on most of the world’s population. It’s inevitable. Every few centuries it’s likely the Earth will undergo vast evolution. This is a film with the ambition to imagine such changes.

I have seen “Cloud Atlas” at least three times now and I still find certain things confusing or baffling. The feral dialect of the far future is not entirely decipherable. But it has not kept me from trying to follow it a little better with each time I see it. I am only vaguely knowing as to why Berry needs to climb a mountain to reset certain power, but I have found other purpose in those scenes, like, the importance is not so much the turn-on of the generator as much as how necessary her appearance is to change Hanks’ destiny. The episode also takes place “106 Years After the Fall,” and is significant for portraying disparate societies rebuilding on Earth following in an unspecific catastrophe that has cut down on most of the world’s population. It’s inevitable. Every few centuries it’s likely the Earth will undergo vast evolution. This is a film with the ambition to imagine such changes.

There is too much action in the film as if to try to meet “Star Wars” type of commercial appeal, or as I first thought, but the film never lingers on gratuitous action. I now find it sensational but in the best way. The action compliments the noble idealizations of its best characters and underlines the inexhaustible evil of its worst characters. The film never puts action “extravaganza” ahead of its ideas.

When the film hits its stride, and it starts making its more significant connections between time, that’s when the film really impacts. More than the action, the renewed spiritual quests are the most sensational aspects of all. I love the music of “Cloud Atlas,” its glorious and triumphant theme by Tykwer, Johnny Klimek and Reinhold Heil. But the film as whole is a symphony of itself. You respond emotionally to things that cannot be described by words.

The still missing lack of description is why “Cloud Atlas” wasn’t hailed as an instant masterpiece, and maybe explains why I was still in a ponderous mode when I first saw it. I had to see it twice. Then three times. Then four. I will see it many more times than that. There is not a boring scene nor a boring shot in the film. The camerawork itself is more expertise than any contemporary Hollywood film today.

I hope the film represents the best of what film can do in the future. Films that are not bound by conventions, by single time periods, by simple themes. Here is one film too vast and beyond the simplistic. “Cloud Atlas” has an unrivaled grandeur and new kind of epic form. Only “The Tree of Life” has reached higher with ambition in recent years. Malick’s film held me faithfully for a couple years. However, I’m currently obsessed with “Cloud Atlas.”

The original novel is by David Mitchell.

172 Minutes. Rated R.

SCI-FI & FANTASY / THINKING MAN’S THRILLER / MASTERPIECE VIEWING

Film Cousins: “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968); “Orlando” (1993); “A.I.” (2001); “The Tree of Life” (2011).

ORLANDO

“Do not fade. Do not wither. Do not grow old.” – Queen Elizabeth I

Of all costume pictures, this is one of the most beautiful and enchanting. Orlando opens as one of the most difficult and challenging films for at least the first twenty minutes – based on the 1928 Virginia Woolf novel, the message and theme are opaque. Until then, your eyes are on fixated on director Sally Potter’s images. Startlingly beautiful it is from frame one, and I mean startling not just stunning. When we talk startling it means that we’re discovering original images of an unparalleled nature that we have not seen like before. Arrangements of candlelight and fog, glass windows and frost, textile patterns and hedge mazes, are presented in ways we haven’t seen. Throw out all expectation for story and surrender to abstract ideas and visual voluptuousness.

Tilda Swinton depicts an English nobleman, androgynous and omnisexual, who flourishes after granted blessings from Queen Elizabeth I in this lavish and picaresque costume epic. Orlando is an ever-transforming character whom changes definition, as well as social title, during a series of episodic exploits.

In the grand realms of the open possibilities of avante-garde cinema this is the costume picture that avoids the usual genre formalities and pigeonholing. What really if you had an extraordinary life with the flexibility that allowed you to wholly indulge in Politics, Romance, Sex and Poetry – at your chosen disposal – when most single lives have time for one true solitary pursuit? I don’t think we really do have time to conquer everything we dream on doing in this lifetime, that’s why I admire this character and this film so unabashedly.

Swinton conveys utmost regality and nimble elegance to her historical set role. Conversely, she has proven through the course of her career that she can play contemporary just as well, whether they are merciless, cold-hearted characters (“Julia,” “Michael Clayton”) or benign, gentle people trapped in difficult circumstances (“The Deep End,” “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button”). But this early film of her career really defines how arty and imaginative she is as a performer.

Billy Zane (“Titanic”) appears as a dashing romantic hero. One of the great images of the film is a simple one: Swinton and Zane side by side in bed, arms entangled, torsos pressed against each other, and Potter’s lithe, supple light on her actors. Somehow Potter creates sensual power out of a commonly staged scene. Love doesn’t last forever – this isn’t a movie about finding ultimate love. But while it does happen it’s stronger in its briefness than most movies ever amount to in full.

“Orlando” is meant for filmgoers who seek out vanguard works that play with experimental and innovative tactics. Its splendidness also lies in landscapes, costumes, art direction as well as the spellbinding creations of mood. To describe the film in matters of specific plot development would be to spoil one of cinema’s most splendid surprises. It passes over 400-plus years ultimately, and ends quite exuberantly, into the future.

“Orlando” is meant for filmgoers who seek out vanguard works that play with experimental and innovative tactics. Its splendidness also lies in landscapes, costumes, art direction as well as the spellbinding creations of mood. To describe the film in matters of specific plot development would be to spoil one of cinema’s most splendid surprises. It passes over 400-plus years ultimately, and ends quite exuberantly, into the future.

93 Minutes. Rated PG-13.

COSTUME DRAMA / PERIOD PIECE / MASTERPIECE VIEWING

Film Cousins: “Spring Summer Fall Winter… and Spring” (2003, South Korea); “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button” (2008); “56 Up” (2013; Britain); “Boyhood” (2014).

MAKE WAY FOR TOMORROW

“Honor Thy Father and Thy Mother.”

Has old-movie musk for about five minutes, but then it grabs you. Make Way for Tomorrow(1937), examines an elderly couple that has to be split up, one of them inevitably headed to an old folks home and the other across the country to California to live with estranged family. It’s about their final day out, after fifty years of marriage, the last hours of togetherness they will be left to have. Director Leo McCarey suggests the Great Depression as a cause to the woes without ever mentioning Great Depression of liberal social injustices. Politics aside, it builds to a heart-shattering conclusion, one fraught of powerful emotion that is incomparable to other films from that time period.

Barkley (Victor Moore) and his wife Lucy (Beulah Bondi) gather their children for a reunion to let them know they have lost their home to the bank. They have a humble plan, which they don’t really share. The children have families of their own, but say they can accommodate them for a short while. Dad will sleep on one of his son’s couches. Mom will sleep on her granddaughter’s bed in another’s son’s home, both addresses divided by distance.

Lucy interrupts her daughter-in-law’s bridge game, simply by having a presence in the home. The granddaughter takes her to the movies and then deserts her there, and leaves her waiting until afterwards. Lucy is yelled at later for lying on behalf of the granddaughter who was sneaking away with boys. It’s only been a short while, but Lucy is already wearing out her welcome.

The quarters aren’t too swell for Barkley either. It’s a cramped space, he catches pneumonia and must recover, and damn it all, is decided by his son that it’s just not working out. Barkley still believes he can rebound, get a job after being jobless for four years, and let his wife move back in with him somewhere. He knows his skills are outmoded, but he tries his best.

In both cases, Barkley and Lucy are a burden to their children who are much too busy to take care of them “properly.” The inevitability comes that one of them will have to move to California to be looked after by a daughter (one of the children we never see). The kids prepare a farewell dinner for their folks, but nary comprehend they want their own privacy. Barkley and Lucy find themselves on a fine day out in New York City, a reminiscence of their honeymoon, and become not so certain they want to share this day with their children.

They have some luck. A car dealer accommodates them to a ride in a fancy automobile after he mistakes them for rich. When the dealer realizes they have no money, he doesn’t get surly but is glad to have fulfilled a special moment for them. Barkley and Lucy recall the Vogard Hotel from years back, and ask to be dropped off there. They are pleased it’s still standing, and go in for cocktails. A little buzzed, they are at ease away from their kids. They recount the history of their love story, speak of regrets, define their love for one another. All these moments are so touching to see them respond to each other in the way they do.

These are great performances for not only the 1930’s but for all-time, and the shock is that Moore and Bondi are playing characters in their 70’s, but were younger actually. Moore was 61, while Bondi was not yet 50, both of them craggily embodying their characters. I suppose I’m more touched by Bondi in a number of her nuances, if I had to pick one over the other. Here’s Lucy, her character, who is older than 70 but still remembers what it’s like to be 25. It’s her body that has defeated her. The Great Depression, the hard times and struggles of not enough food or substantial exercise, would be one cause for accelerating old age.

These are great performances for not only the 1930’s but for all-time, and the shock is that Moore and Bondi are playing characters in their 70’s, but were younger actually. Moore was 61, while Bondi was not yet 50, both of them craggily embodying their characters. I suppose I’m more touched by Bondi in a number of her nuances, if I had to pick one over the other. Here’s Lucy, her character, who is older than 70 but still remembers what it’s like to be 25. It’s her body that has defeated her. The Great Depression, the hard times and struggles of not enough food or substantial exercise, would be one cause for accelerating old age.

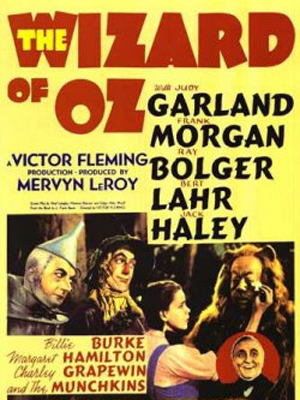

“The Wizard of Oz” is the greatest film of the 1930’s, and while I love “City Lights,” “Trouble in Paradise” and King Kong,” the long forgotten “Make Way for Tomorrow” would be my number two selection. For one, the uncompromising ending which McCarey refused to re-shoot despite studio executives desire to change it. Barkley is catching the train, he must say his goodbyes, but to hide it they say to each other this is all just for now. The versatile McCarey won a Best Director Oscar in 1937 but it was for his screwball comedy “The Awful Truth.” When he went up to the podium he said, “I would like to thank the Academy, but you gave it to me for the wrong picture.”

92 Minutes. Unrated.

DRAMA / YOUNG TEENS AND UP / MASTERPIECE VIEWING

Film Cousins: “Umberto D.” (1952, Italy); “Tokyo Story” (1953, Japan); “On Golden Pond” (1981); “Amour” (2012, Austria).

STRAIGHT TIME

“I just wanna be like everybody else. I just want a decent job. I want a decent place to live. I want somebody to love me, I want some clothes on my back.” – Max Dembo

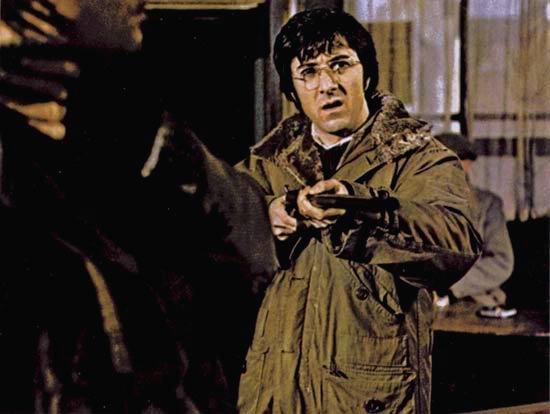

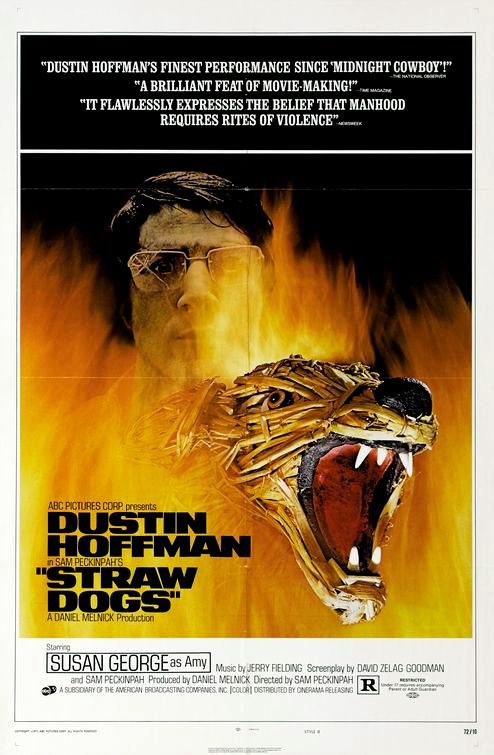

The great Dustin Hoffman performance you’ve never seen playing convict on parole Max Dembo, actually it’s one of the best performances ever period. Straight Time (1978) is as obscure a masterpiece you will find, it was brushed under the rug with such disregard that Hoffman sued Warner Bros. over the treatment of the film. Hoffman found the book “No Beast So Fierce” written by Edward Bunker, an actual San Quentin convict still serving, and exhaustively researched the part. Hoffman began directing the film, but decidedly could not handle double duties. He called Ulu Grosbard, the man who gave Hoffman the book to read, to replace him in the director’s chair. The character Dembo refuses a halfway house, finds his own dirt-cheap living quarters, acquires a job at a can factory – but his own parole officer, played by the pernickety and strident M. Emmit Walsh, actually loses him that job (“Over nothing, man!”), and after a blown temper and irreversible outburst of attacking of him, Dembo finds himself a fugitive of the law once again.

Reverting back to his old ways, Dembo finds a liquor store, a poker game holdup, and a bank robbery as scores to live off. Dembo never really had a chance to go straight anyway, because all his contacts are criminals working the angles 24/7. Bunker told Hoffman the key to the performance is to find nothing morally wrong in robbery, murder and malfeasance. Hoffman, diminutive in stature, is able to come off as a threat because he is so convincingly sociopathic. Harry Dean Stanton, Gary Busey and Corey Rand play moonlight thieves that partner in crime. Stanton’s best line: “I’m telling you it’s very un-f***ing-professional, all right!”

The hardest thing for the movie to pull off is Dembo’s relationship with Jenny Mercer (Theresa Russell), a contact at a job placement agency who becomes his girlfriend. Jenny has no good reason to keep seeing Dembo after he admits he has broken the law. But she’s one of these girls that’s attracted to helping and abetting bad guys. I’ve accepted Russell in this role after seeing “Straight Time” several times, but it occurred to me in this last viewing, that if it had been any other actress the whole character would have been malarkey. I see Jenny as a bored, limited experienced girl who is blind to danger, and pitying. I also guess that her unseen parents have bought her the house she lives in, and she basically cruises through life feeling she is consequence-free.

The hardest thing for the movie to pull off is Dembo’s relationship with Jenny Mercer (Theresa Russell), a contact at a job placement agency who becomes his girlfriend. Jenny has no good reason to keep seeing Dembo after he admits he has broken the law. But she’s one of these girls that’s attracted to helping and abetting bad guys. I’ve accepted Russell in this role after seeing “Straight Time” several times, but it occurred to me in this last viewing, that if it had been any other actress the whole character would have been malarkey. I see Jenny as a bored, limited experienced girl who is blind to danger, and pitying. I also guess that her unseen parents have bought her the house she lives in, and she basically cruises through life feeling she is consequence-free.

The movie builds to a smash-and-grab jewelry store robbery that is terrifically suspenseful, especially when the getaway car doesn’t go as planned, and the thieves run through the houses and alleys of the neighborhood (Kathryn Bigelow’s “Point Break” would later take this scenario to the next level). Dembo comes to realize that his acts of larceny aren’t going to last forever, that he’s bound to get caught, so he might as well act out his crimes in bigger and bolder style anyway. This is inevitable when someone like Dembo has spent the majority of life as a criminal and convict. The final droll montage of Dembo through the years sums that up – someone this scary, doomed material has elicited a big laugh.