It’s easy to lap up wet kisses in adoration for Joel and Ethan Coen, whom with “No Country for Old Men,” “Burn After Reading” and “A Serious Man” mark themselves as among the best filmmakers currently. But besides them, Kim Ki-Duk of South Korea has me in a tighter enthusiastic grip than anybody else in the world right now. I first discovered “3-Iron” (2005) on Netflix in December 2008. It was on my queue for awhile. For so long that I could never remember what prompted me to put it on my queue in the first place.

After awhile, after you are fully acquainted with Kubrick, Scorsese, Eastwood, Aronofsky and all the other majors, you will get hungry to taste some exoticism. In the last couple of years, I have developed a fascination with Korean cinema. The most creative and thematically rich cinema in the world has to be Korean, according to what I’m seeing and compared to what we have here. That’s not to say that there isn’t a bounty or more American films that float my boat. But the foreign-ness, the exoticism, is so mind-opening that you become aroused by the possibilities.

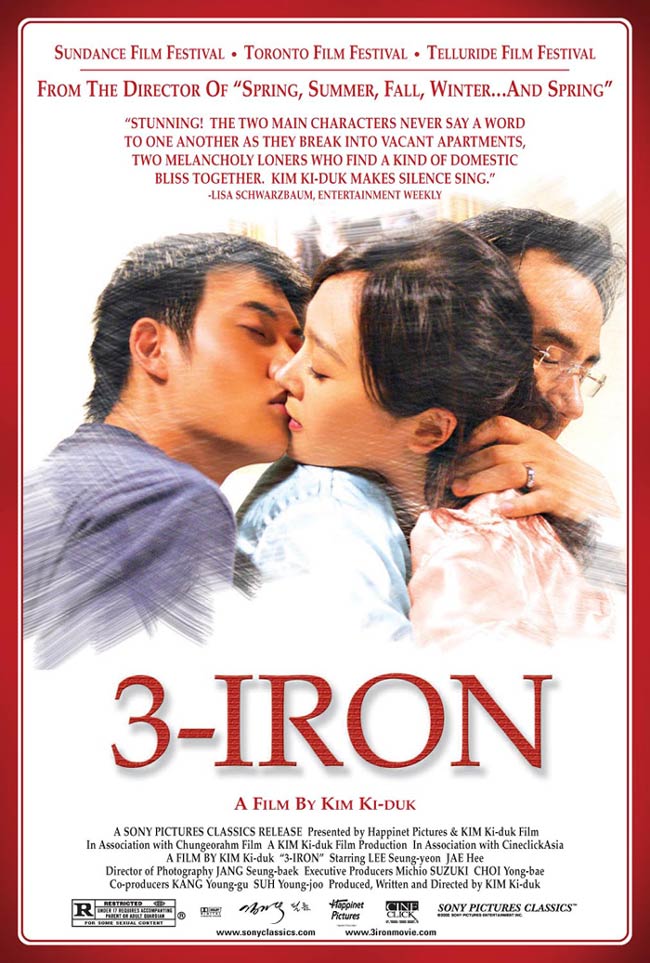

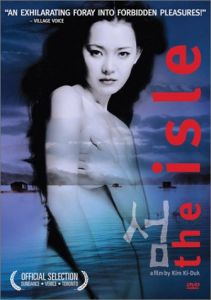

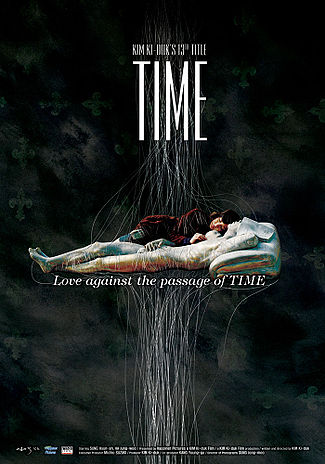

Where would I be without the films of Korea’s Kim Ki-Duk? “3-Iron” (pic left) is a beautiful and spiritually deep love story; “The Isle” is a mind-bending allegory on controlling others thru sex; “The Bow” is as upsetting film I’ve seen about the lengths men will go through to possess beauty; “Samaritan Girl” contains audacious material too salacious to ever find its way into an American film; “Time” is the most haunting relationship movie I’ve seen — it almost cuts too close to the bone. “Address Unknown” is one of the most despairing movies I’ve ever seen, examining Korean citizen poverty in a region outside of a U.S. army base; “Birdcage Inn” about a family so poor they send their daughter to school by day and prostitute her at night, until a beautiful girl is hired to take over; “The Coast Guard” about a soldier’s guilt after the accidental killing of a local citizen, interesting drama until the protagonist becomes a symbolic abstraction. Accumulatively, these films have changed what I’m looking for when I watch film. All these films are within the last ten years.

Where would I be without the films of Korea’s Kim Ki-Duk? “3-Iron” (pic left) is a beautiful and spiritually deep love story; “The Isle” is a mind-bending allegory on controlling others thru sex; “The Bow” is as upsetting film I’ve seen about the lengths men will go through to possess beauty; “Samaritan Girl” contains audacious material too salacious to ever find its way into an American film; “Time” is the most haunting relationship movie I’ve seen — it almost cuts too close to the bone. “Address Unknown” is one of the most despairing movies I’ve ever seen, examining Korean citizen poverty in a region outside of a U.S. army base; “Birdcage Inn” about a family so poor they send their daughter to school by day and prostitute her at night, until a beautiful girl is hired to take over; “The Coast Guard” about a soldier’s guilt after the accidental killing of a local citizen, interesting drama until the protagonist becomes a symbolic abstraction. Accumulatively, these films have changed what I’m looking for when I watch film. All these films are within the last ten years.

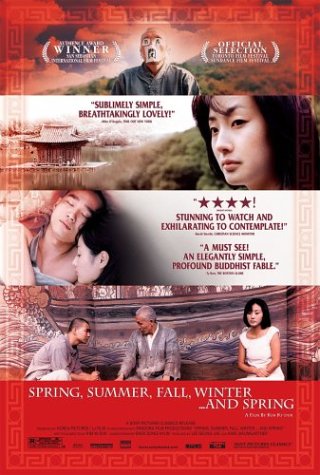

Then there is Kim Ki-Duk’s “Spring Summer Fall Winter… and Spring” (2003, pic article top) which initially prompted me to re-examine my inner spiritual study and initiate my interest in Buddhism. Then after months of contemplation, and the realization that I was watching it over and over, and the realization that I was using its principles towards the way I live on an every day basis, I came to a declaration that it is the best film ever made. Do I say it is the best film ever made just so I can be different? To get attention? No, I say it is the best film ever made because it is the best film ever made. The world would get better if all of us sat down to watch it and discuss it. There will be other blogs that will discuss it more thoroughly.

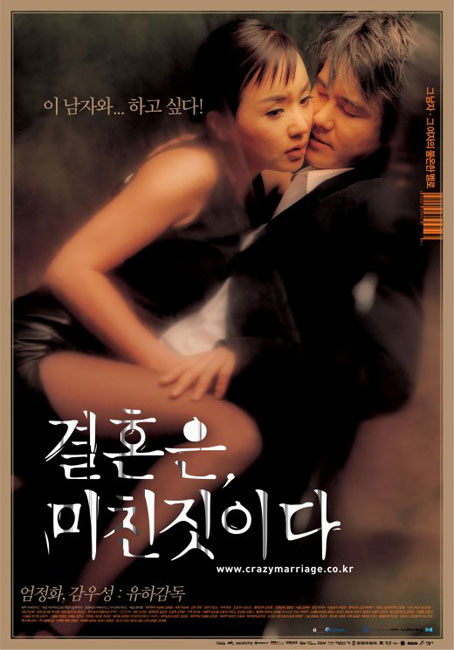

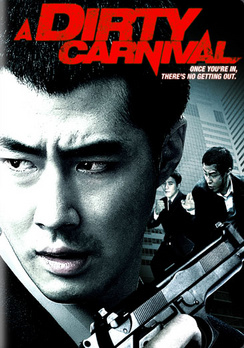

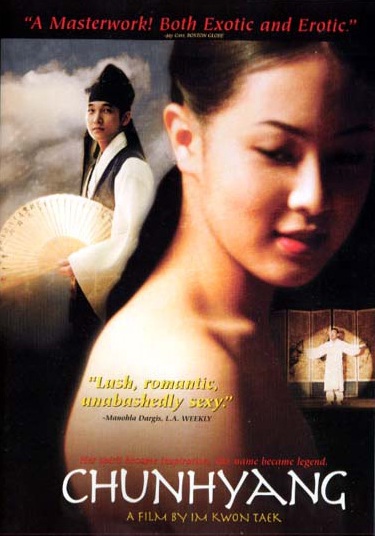

And perhaps discuss the films of Ha Yoo, who made two great pictures with “Marriage is a Crazy Thing” (2002, poster bottom left) and “A Dirty Carnival” (2006). Or the films of Hong Sang-soo, so empathetic of women, who made “Woman is the Future of Man” (2004) and “Woman on the Beach” (2006). There are another half dozen interesting filmmakers from South Korea, really. Chan-wook Park (“Oldboy” 2005, “Thirst,” 2009), two shockeroo thrillers, might be the most well-known in the States. Im Kwon-taek is highly respected and I’m particularly drawn by the 18thcentury set romantic saga “Chunhyang” (2000) – what escalates is terrible, and yet how passionate, bold and sumptuous it is elevating to the realms of elegant tragedy.

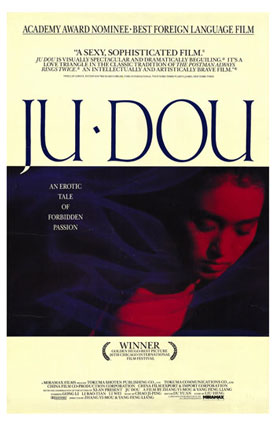

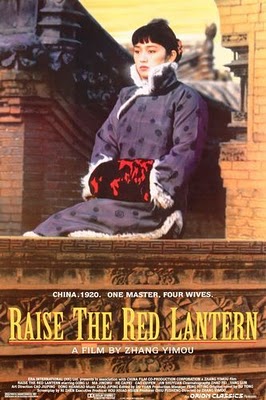

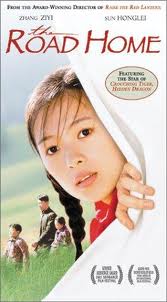

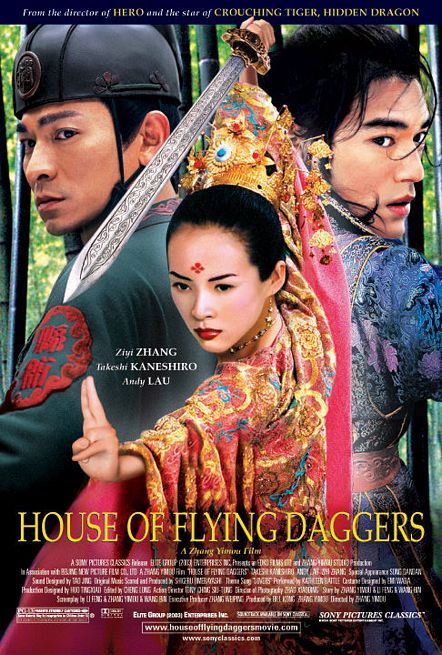

But is it just Korean cinema? I found Chinese cinema in the 1990’s as a forefront ambassador. Zhang Yimou was doing his best work then. “Ju Dou” (1990) has some beautiful dye-colors and it is so erotic in a way that stands apart from American film. “Raise the Red Lantern” (1991) about four rival concubine wives in an enclosed 1920’s palace could be the best of them. I never understood what the Chinese civil and Cultural Revolution of the mid-20thcentury was about until I saw “To Live” (2004). The Shanghai mafia of the 1930’s is brought voluptuously to life in “Shanghai Triad” (2005). The most gentle and moving love story I have ever seen is “The Road Home” (2000) with Zhang Ziyi as a simple girl trying to find the right time of day to cross paths with the village schoolteacher in a time and place that didn’t allow girl pupils. Since then, Yimou has delivered awesome martial arts historic and fantasy pics that became international sensations with “Hero” (2002), “House of Flying Daggers” (2004) and “Curse of the Golden Flower” (2007).

I know, there are other Chinese filmmakers to speak of like Edward Yang but despite some of the best reviews around the world his “Yi Yi” (2000) is a crushing bore. Ang Lee is an obvious one. Before he went Hollywood he made “Eat Drink Man Woman” (1994), though he did return home for “Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon” (2000), a worldwide smash pay-off, which after a recent viewing I’m convinced is one of the most visually splendid films ever to be seen. John Woo was, outside of the terrific “Face/Off” (1997), was never as good in America as when he started in his homeland. “The Killer” (1989) and “Hard Boiled” (1989) are exuberant, elaborately choreographed guns-and-revenge classics. Then there are always the enjoyable Jackie Chan pictures, particularly “Supercop” (1993) and “The Legend of Drunken Master” (1994), although I wouldn’t be able to remember who directed them without using a crib sheet.

The obvious filmmaker representing Japan has always been Akira Kurosawa. He just simply has always represented, he is the key figure for newcomers to Asian film and an undying staple for cinephiles. I have always cared less for his samurai films like “Seven Samurai” (1954) and “The Hidden Fortress” (1958) – although they still impart a vision that holds up – then I have for his puzzle film “Rashomon” (1950), or his stark drama of a dying man who attempts to fulfill one last good deed to make one positive mark in life in “Ikiru” (1952), or his Shakespearean take on Macbeth with “Throne of Blood” (1957), or the extortion picture where a corporate boss must choose between saving his company or paying ransom for his chauffeur’s kidnapped son in “High and Low” (1963), one that might eventually get remade by the Coen Brothers. Kurosawa made less films in his last two decades but is known for “Kagemusha” (1980) and “Ran” (1985), both filled with ravishing images but, for me, a tad heavy with portentous running times. I prefer his avant-garde “Dreams” (1990) which is a collection of eight vignettes.

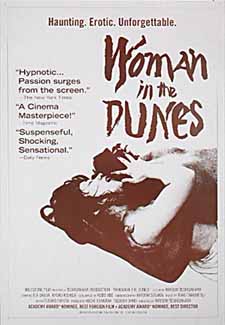

Kurosawa is a master, but less known is Hiroshi Teshigahara whose “Woman in the Dunes” (1964) for me is the best Japanese film ever made. The great desert sand film, according to mainstream lore, has always been “Lawrence of Arabia” (1962) but that’s only because many have never seen the Teshigahara film which breaks open the conventional possibilities of what you can do and how you can photograph sand. If you’ve never seen it, how can you judge? Imagine “The Truman Show” (1998) without cameras but with observers perched atop sand dunes, and people lodged in the dunes like inhabitants of an ant colony. It’s as Roger Ebert put it, a parable about life. I also recommend Teshigahara’s eerie tale “Pitfall” (1962) about laborers haunted by a ghostly autocrat.

In Japan, I also discovered the tender parable about living an honest life and honoring the people around you with Yojiro Takita’s “Departures” (2008) which won the Oscar for Best Foreign Film. Japan is often cited with augmenting The Asian Extreme movement, but the best in horror is the more psychologically layered “Audition” (1999), which gathers power by making the implausible look plausible. Not for everybody: it could f*** up your head for months. And again on the more gentle side, one cannot overlook Yasujiro Ozu’s “Tokyo Story” (1950) about the regrets ofgrown children neglecting their parents in their first ever visit to the big city. Or “Late Spring” (1949) about an arranged marriage in post-World War II Japan. Two masterpieces.

I could jump around all day. What I don’t know much about admittedly is anything on Thai or Vietnamese cinema (“The Scent of Green Papaya” from 1993 has been on my Netflix queue forever, marked as unavailable). What I do know is that Korean cinema has boomed in the last 15 years, and is a model leader for adventurous thinking man’s cinema. Chinese cinema has gone up and down in quality over the years but Yimou is still its greatest contributor. Japanese cinema has always been interesting over the years. Interesting? More than just that. And just generally, films from Asia have said something about honor, discipline, old heritage customs, and then just some good old fancy costumes and fancy eroticism that is so estranged in American cinema.