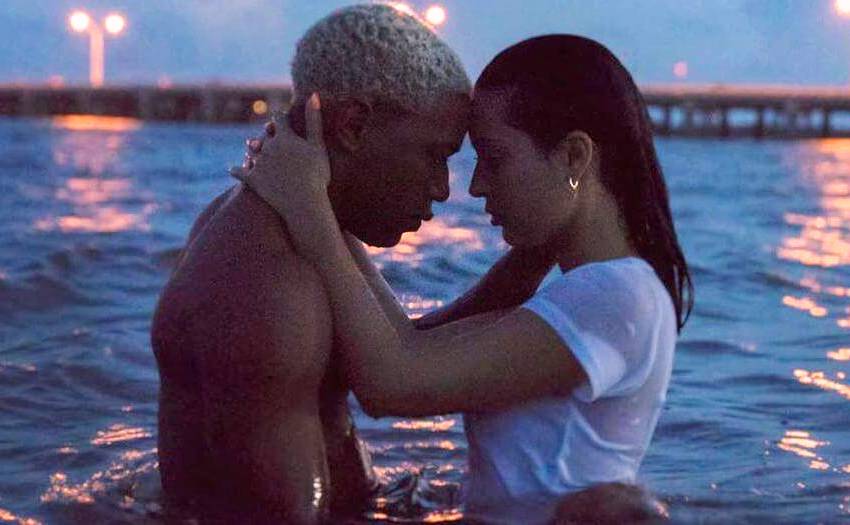

The film is called Waves, but Trey Edward Shults’ film is about the two different speeds a brother and sister share within an affluent African-American family. Tyler (Kelvin Harrison Jr.) is an on-the-go overachiever who is an excelled student and a wrestling star; he needs no one to tell him to run eight miles after school, and then one shot also shows he has the versatility to master piano. He also finds the time to hang with friends at parties or chill with his girlfriend who is as fit as he; tirelessly he is on a higher plateau than his peers in being seemingly well-rounded. Emily (Taylor Russell) is the introvert sister who gets less attention in the household, needing very little encouragement to keep her extra-curriculars in focus. She goes about her business quietly.

Breathless seconds in, Waves has already come on shooting on all cylinders like a Scorsese or Malick film, so natural and unchained it could be mistaken for a bona fide one. Shults uses his camera like a psychological lightening rod anatomizing the essential daily fragments, or at other times a whirling spinning top capturing the euphoric momentum of life. Visually, it is always hurling ahead with impromptu poetry.

Life under the Florida sun is golden. Then some setbacks suddenly occur, and we are undoubtedly in the hands of a drama that in its foreboding is heading towards a calamity – we sense something. Waves has uncontrolled sprawl and spontaneity, and so you won’t know what will happen unless another review has spoiled it for you; I, for one, got to see this brave, radical film going in blind.

It is suggested an African-American family can live this well off only because the patriarch has worked his tail off. The father (Sterling K. Brown) is the type to remind his son after school to work with a better vocabulary, at night he gets his son to work on the family business bookkeeping. When they work out together and he coaches his son to keep struggling his way up to work with heavier and heavier weights; the hounding message is always focus and work harder (the stepmother played by Renée Elise Goldsberry, is a more hands-off loving force). The unsaid but implied statement of the script though is that many whites can’t have what this family has because they would never work this fervently in their quest to achieve. From the outside, the Williams family is one to envy.

On the inside, though, sometimes disappointment or disorder is hard to navigate for some people who don’t have the coping mechanism, and instead of a family sounding board available to express doubts and concerns there are self-retreating chambers one can unhealthily drill themselves into.

I faintly recalled a number of directors, as varied as Bergman or Coppola or Spike Lee who were experts at mounting dread. But while I was engrossed with Waves I couldn’t think of what closest comparison there was to anything happening before my eyes here. There had been hundreds of films in my past that summoned a commotion of anxiety and apprehension, but Shults’ film was moving so fast – moving so fast towards something! – that, in the moment, it felt singular.

Waves becomes an appropriately divided split film at one point, indeed adapting to a new speed to operate on (the bisect structure of “Chungking Express” did this, but not with the everything-is-connected karmic impact of Waves). Lucas Hedges (“Boy Erased,” “Lady Bird”) enters the picture as Luke; once again the versatile actor works miracles in fine-tuning his intelligence and emotive barometer to create a character sensitive to the specific environment – the dialing of his range is ever subtle.

All the other actors are probably more remarkable, but I must tread carefully in describing their performances – let’s just say everyone is praiseworthy. It is important though to mention Hedges, that the character Luke becomes the beacon of grace – humble, unassuming, thoughtful – that desperately fills in a void for the Williams’, and with this forged relationship, the angst can beautifully be set free.

Lyrically, the highly revered “Moonlight” didn’t have such a fierce tenor or elevating rapture as this. Momentarily, I will belatedly be revising my Ten Best List for 2019, because I always try to do the right thing.

POST-SCRIPT: This is Shults’ third film; his first “Krisha” was enclosed entirely inside a Thanksgiving family reunion which sounds tiresome, but with its suggestive frantic sound design and off-kilter tonal shifts, it turns into a legit art film (when it gets to business, think of Bergman’s starkest 1970’s works) about one family’s possible intolerance for a 60-year old former addict who has shown up. His second “It Comes at Night” was a gimmick exercise albeit a well-directed one that didn’t come around in completely satisfying. With Waves, as glorious as its’ abstract notes are, the only thing I could have asked from it was a more sentimental finish to it because I felt like it would have been earned. Shults shouldn’t be afraid of big hugging moments if he’s earned them.

135 Minutes. Rated R.

Film Cousins: “The Virgin Spring” (1961); “Rumble Fish” (1983); “Jungle Fever” (1991); “Krisha” (2016).