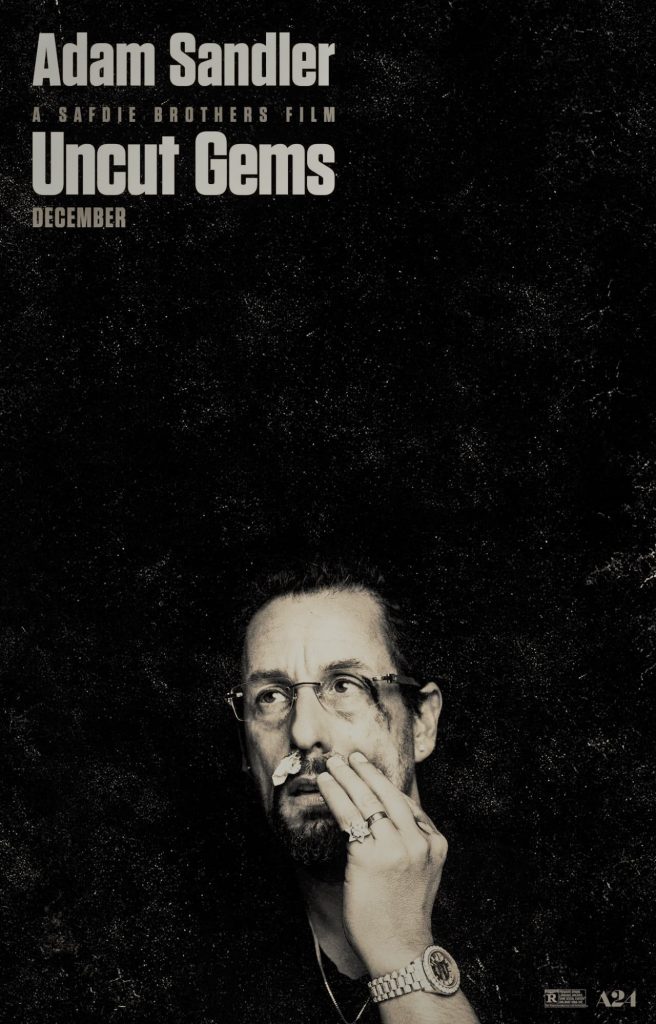

The movie of the year, and more, Adam Sandler is unleashed in what is one of the fifty greatest performances I’ve ever seen; Sandler is blustery and raging, chancy and impulsive, jealous and truculent, high-wire and manic, and very, very hysterical in his need to risk everything and go for broke.

I’m not even sure at what point did I realize that I did not like Sandler’s New York Diamond District jeweler Howard Ratner. I had realized the film was indeed self-aware when his fed-up wife (Idina Menzel) called him annoying. Uncut Gems is not about a decent individual trying to climb out of a hairy predicament, it’s about an indecent man sunk in a thicket of scams and deliberately driving himself more into riskier and riskier endeavors.

This is very much a portrait of how the type of downtown hustler lives, the hustler who plays with stacks of ten large and above on a daily basis, and here’s a guy who is willing to pawn his celebrity customer’s prized ring so he can gamble with their money on a “sure thing.” Uncut Gems is like 1974’s “The Gambler” refiltered through the neorealism of the Dardenne Brothers and recharged with the style of early Quentin Tarantino while on a super high dosage of Ritalin.

Howard’s worst trait is his presumptuousness, but if there is something he earnestly wants from another person he can turn on a dime and buy that person’s confidence — particularly a scene where he wills a basketball player to play the best to his given ability; the gambling scenes in effect have zero predictability in Uncut Gems, since we don’t know if a particular player is going to play on full blast on Howard’s behalf or strike out in spite.

When we get to the last act, Sandler is in a must-win situation while his street smart adversaries are for a short time in a chamber held up. And damn if, vicariously through Sandler’s frantic yet little boy giddiness, we don’t clench our fists in our mouths as we wait on a deliverance or failure of a bet to follow through. Jolted by Sandler’s ecstatic acting, it is irrefutably the most heart-racing, electrifying sequence to have been had at the movies this year and I knew right then that solidified it as my #1.

The Safdie Brothers (Josh and Benny) directed, who got Martin Scorsese to be their Executive Producer to go to bat for them. Uncut Gems was originally written in 2009 and shopped around by 2012 before many of their other projects would happen first (Adam Sandler and Jonah Hill turned them down that year). When Robert Pattinson took a liking to them at a party, the Safdie Brothers wrote “Good Time” specifically for Pattinson. Following that success, Sandler had new confidence in them, and the Safdie Brothers finally landed funding for Uncut Gems, a lived-in gritty and sure thing masterpiece and they’re both only in their mid-thirties. And Sandler’s marvelous acting in 2002’s “Punch-Drunk Love?” Not a fluke. I disagree. I disagree, Gary. He’s way upped his game from that.

James Woods as New York City cop with a short-fuse, on the trail of a mass murderer known as The Party Crasher (Stephen Lang, doing one-note psycho). The case has been obsessing him, but the Police Captain takes him off the assignment and told to do a ride along with Hollywood action comedy star Nick Lang (Michael J. Fox) who wants authentic experience for acting research. Woods, as Lt. John Moss, doesn’t give a damn about protocols, and he prescribes his own duties. Doesn’t give a damn if a Hollywood brat gets hurt along the way.

Much of <em>The Hard Way</em> is riotous and entertaining. When I saw it years ago, I thought it was an alright buddy cop gimmick with some slick thrills. I see it today, and observe how director John Badham (“Saturday Night Fever,” “Stakeout”) has a knack for grimy milieu and profane thrills—it’s not a sugary movie, far from it. The look is practically neo-noir.

If anything, too much nihilism bogs it down. Constant gang warfare and subway thug attacks and flipping cars and hanging off billboards gets coarse.

Everything that’s character-detailed, on the other hand, is super. Fox immediately gets on Woods’ nerves and it’s uproarious watching this Popeye Doyle-like cop flare up and, hold back, then hold back some more, then inevitably blow his lid. <em>“I don’t want you inside my skin, you understand!”</em>

Woods has a sliver of a tender side, when he’s trying to court his new girlfriend (Annabella Sciorra); in one of the comic highlights, Fox tries to teach him how to talk to women by putting on an effeminate voice, for sake of role-playing. What’s funny about Fox is that he’s in touch with his sensitive side, a spoiled big shot who quotes his nutritionist and other La La Land gurus.

Fox gets a rude awakening from Woods, who busts the chops of every deadbeat in New York until he can trap The Party Crasher. The result is a helluva comedy. If only the movie wasn’t so aggressively violent every few minutes. But I forgive. Woods and Fox often crack me up.

135 Minutes. Rated R.

DRAMA / ADULT ORIENTATION / MASTERPIECE VIEWING

Film Cousins: “Mean Streets” (1973); “The Gambler” (1974); “The Killing of a Chinese Bookie” (1976); “Good Time” (2017).