The last two years I’ve seen list after list of the Top Ten Films Ever. Why 2012 and 2013 inspired this, I don’t know. I had thought of doing a list the last few years to give readers an idea of what kind of films I stand behind. Still, I hadn’t been prompted to go through with it and do my own until I happened to have stumbled onto a comment on EW’s website when they did their Top Ten online where the reader was irked by sheep-like obvious choices. I instantly thought of my own picks and figured, yes, I’m sure even the film connoisseur might be unfamiliar with three or four of my choices. I am happy to impart selections that might be new for you, since discovering something new is what loving cinema is all about. And while “No Country for Old Men” is a well-known title, the inclusion of it might be a shock to some of you for being too new and untested by time. As it turns out, a couple more titles are obvious and yet it would have been phony of me to not include them. If you find a new film to love by the end of the week, then I’ll have done my duty. Or at least re-evaluate your appreciation of a film you saw but hadn’t embraced before. Thank you for reading.

1. Spring Summer Fall Winter… and Spring (2003, South Korea) – Kim Ki-Duk’s immersive spiritual journey can be carried with you in your heart and mind, day to day, for now and for the future, from birth to old age. After seeing it, and letting yourself digest it, the euphoria of discovery might be your new birth. In the world’s most singular beautiful location, set on a Buddhist pagoda floating on a lake, a monk (Yeong-su Oh) cares after a young boy (Jong-ho Kim) he is raising to be a monk. We see their daily rituals and then we see broken rituals. As the seasons pass, the film leaps years ahead. We witness the faults of the young boy and then his journey to renewal. We witness the joys of sex, the joys of solitude, and the doubt that lives in-between. The value of self-purpose and destiny, the value of waiting years for a revolving door to happen and the value of waiting years for penance. Aesthetically, this as beautiful as cinema gets. Pace-wise, it moves along limber and amble, and conquers an amazing amount of ground in a scant 103 minutes. “Spring” inspires years of awesome reflective contemplation. Adults only.

1. Spring Summer Fall Winter… and Spring (2003, South Korea) – Kim Ki-Duk’s immersive spiritual journey can be carried with you in your heart and mind, day to day, for now and for the future, from birth to old age. After seeing it, and letting yourself digest it, the euphoria of discovery might be your new birth. In the world’s most singular beautiful location, set on a Buddhist pagoda floating on a lake, a monk (Yeong-su Oh) cares after a young boy (Jong-ho Kim) he is raising to be a monk. We see their daily rituals and then we see broken rituals. As the seasons pass, the film leaps years ahead. We witness the faults of the young boy and then his journey to renewal. We witness the joys of sex, the joys of solitude, and the doubt that lives in-between. The value of self-purpose and destiny, the value of waiting years for a revolving door to happen and the value of waiting years for penance. Aesthetically, this as beautiful as cinema gets. Pace-wise, it moves along limber and amble, and conquers an amazing amount of ground in a scant 103 minutes. “Spring” inspires years of awesome reflective contemplation. Adults only.

2. Walkabout (1971) – Two lost children stagger through the Australian outback accompanied by an Aboriginal boy on his exodus calling to claim his manhood. Jenny Agutter and Luc Roeg are the beautiful teen girl and pubescent younger brother, who were certain to doom before they met their guide. I imagine myself as a city person like them lost in the wilderness. I am molded by my urban surroundings, conditioned and programmed just like these two. Force me to a few days in the Outback with no experience, I am impotent and desperate. Give me a guide to teach me and grant me the time to adapt over several weeks, I will persevere and become fond of my new lifestyle. Like all great films possess, “Walkabout” invites you to a part of the world you’ve never seen. Globetrotter Nicolas Roeg made 15 theatrical films, three of them are eternal masterpieces (along with “Walkabout,” the trippy mind-bender “The Man Who Fell to Earth” and the supernatural tale “Don’t Look Now”). His layout of images and sequences are often non-linear, more describable as mosaics in the way he overlaps images and sneaks in elliptical visual information. The result is thematically and emotionally enigmatic and yet splendidly fluid, and if you’re like me, you can watch it year after year for life.

2. Walkabout (1971) – Two lost children stagger through the Australian outback accompanied by an Aboriginal boy on his exodus calling to claim his manhood. Jenny Agutter and Luc Roeg are the beautiful teen girl and pubescent younger brother, who were certain to doom before they met their guide. I imagine myself as a city person like them lost in the wilderness. I am molded by my urban surroundings, conditioned and programmed just like these two. Force me to a few days in the Outback with no experience, I am impotent and desperate. Give me a guide to teach me and grant me the time to adapt over several weeks, I will persevere and become fond of my new lifestyle. Like all great films possess, “Walkabout” invites you to a part of the world you’ve never seen. Globetrotter Nicolas Roeg made 15 theatrical films, three of them are eternal masterpieces (along with “Walkabout,” the trippy mind-bender “The Man Who Fell to Earth” and the supernatural tale “Don’t Look Now”). His layout of images and sequences are often non-linear, more describable as mosaics in the way he overlaps images and sneaks in elliptical visual information. The result is thematically and emotionally enigmatic and yet splendidly fluid, and if you’re like me, you can watch it year after year for life.

3. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) – The ultimate head trip. Every Stanley Kubrick directed image is majestic, and yet, it’s not the same film if you’re watching it on home video. Seeing it on the big screen in a 70mm format is the spectacular way to go. Then you still have to be open to interpreting the mind-bending allegory of the film. I’ve noticed that adults that tune in to catch this late in life have lost their ability for the abstract thought that is required, and are the ones turned off by the idea of meditative cinema over plot. I saw this first at 8-years old when my mind was still shaping, and it filled me with wonder and abstract thought. “2001” meditates on spectacle, the beauty of space, the pros and cons of technology, the struggle between man and the machine that out-thinks him, the mystique of deep space, and the possibilities of evolution that is beyond our current rudimentary concepts. Behold the beauty though, it’s cinema’s most euphoric trance-out.

3. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) – The ultimate head trip. Every Stanley Kubrick directed image is majestic, and yet, it’s not the same film if you’re watching it on home video. Seeing it on the big screen in a 70mm format is the spectacular way to go. Then you still have to be open to interpreting the mind-bending allegory of the film. I’ve noticed that adults that tune in to catch this late in life have lost their ability for the abstract thought that is required, and are the ones turned off by the idea of meditative cinema over plot. I saw this first at 8-years old when my mind was still shaping, and it filled me with wonder and abstract thought. “2001” meditates on spectacle, the beauty of space, the pros and cons of technology, the struggle between man and the machine that out-thinks him, the mystique of deep space, and the possibilities of evolution that is beyond our current rudimentary concepts. Behold the beauty though, it’s cinema’s most euphoric trance-out.

4. GoodFellas (1990) – Robert DeNiro, Ray Liotta and Joe Pesci in the untouchable Martin Scorsese film that immortalized them. We are taught by grade one that murder, robbery, loan sharking and all that other mayhem stuff is a sin. We know that these wiseguys are a bad morally corrupt outfit and yet it is so appealing and tantalizing that you can’t help but fantasize about being a part of it. “The Godfather” is a classic handsome Greek tragedy of a film, but have you ever fantasized about being one of the Corleones? I’d rather be a GoodFella: The cars, the booze, the nightclubs, the all-night card playing, the stacks of money, the mistresses, the fur coats, the ball-busting… and the prison scenes, when they are incarcerated, are made out like a health spa. The problem is the 1950’s and ’60’s didn’t last forever, for the drug trafficking of the ’80’s tarnished the coolness of gangster life. Anyways, if you have never seen a Scorsese film, which should be a constitutional duty in this lifetime, then start here. When you see the camera tour through a red-lamp nightclub via the backdoors through the service entrance, passageway the kitchen, and then passageway onto its service floor where Liotta and Lorraine Bracco get seated at their exclusive table, you will begin to understand why Scorsese is such a huge deal.

4. GoodFellas (1990) – Robert DeNiro, Ray Liotta and Joe Pesci in the untouchable Martin Scorsese film that immortalized them. We are taught by grade one that murder, robbery, loan sharking and all that other mayhem stuff is a sin. We know that these wiseguys are a bad morally corrupt outfit and yet it is so appealing and tantalizing that you can’t help but fantasize about being a part of it. “The Godfather” is a classic handsome Greek tragedy of a film, but have you ever fantasized about being one of the Corleones? I’d rather be a GoodFella: The cars, the booze, the nightclubs, the all-night card playing, the stacks of money, the mistresses, the fur coats, the ball-busting… and the prison scenes, when they are incarcerated, are made out like a health spa. The problem is the 1950’s and ’60’s didn’t last forever, for the drug trafficking of the ’80’s tarnished the coolness of gangster life. Anyways, if you have never seen a Scorsese film, which should be a constitutional duty in this lifetime, then start here. When you see the camera tour through a red-lamp nightclub via the backdoors through the service entrance, passageway the kitchen, and then passageway onto its service floor where Liotta and Lorraine Bracco get seated at their exclusive table, you will begin to understand why Scorsese is such a huge deal.

5. All That Jazz (1979) – Bob Fosse’s glitzy showbiz musical that is a reinterpretation of Fellini’s “8½…” and outdoes it. Joe Gideon (Roy Scheider) is a Broadway Theatre director and choreographer, womanizer, pill-popper, chain-smoker, and ego-maniac. Some men have the natural talent to attract dozens of women at once and Gideon is one of them, juggling many relationships at once. That could be inherently offensive to some, but I’ll tell you, Gideon is open about it and the women are aware of his indiscretions. Excess is a huge theme, some people just can’t help but live fast and reckless, and yes, I admire the people that do that but I am not one of them. The film is a self-indulgent, excessive fantasy and it gets more avante-garde as it nears the end (Jessica Lange is the exquisite Angel of Death). Fosse is saying, Death can be an individual creation. As entertainment, “Jazz” continues viewing after viewing as the most exhilarating movie out there for me. Best dance movie, and sexiest movie, too.

5. All That Jazz (1979) – Bob Fosse’s glitzy showbiz musical that is a reinterpretation of Fellini’s “8½…” and outdoes it. Joe Gideon (Roy Scheider) is a Broadway Theatre director and choreographer, womanizer, pill-popper, chain-smoker, and ego-maniac. Some men have the natural talent to attract dozens of women at once and Gideon is one of them, juggling many relationships at once. That could be inherently offensive to some, but I’ll tell you, Gideon is open about it and the women are aware of his indiscretions. Excess is a huge theme, some people just can’t help but live fast and reckless, and yes, I admire the people that do that but I am not one of them. The film is a self-indulgent, excessive fantasy and it gets more avante-garde as it nears the end (Jessica Lange is the exquisite Angel of Death). Fosse is saying, Death can be an individual creation. As entertainment, “Jazz” continues viewing after viewing as the most exhilarating movie out there for me. Best dance movie, and sexiest movie, too.

6. Citizen Kane (1941) – Deep focus, low-angle shots, non-linear narrative, radio music accompaniment, the “documentary” newsreel as story overview, the breakfast scene montage which depicts an entire marriage in five vignettes, the matte shots. “Kane” has been hailed so long as such a landmark in technical filmmaking that it has overshadowed the fact that it contains one of life’s most profound messages: How to not be unhappy like Kane. In addition to directing, Orson Welles is Charles Foster Kane in this thinly veiled exposé of mogul William Randolph Hearst. Charles is given away by his poor parents to a rich surrogate father, grows up into an idealistic young man who starts a newspaper, ebulliently expands his media to nationwide syndication, vainly steps up into political ambition, and builds himself the mother of all mansions. Except the ostentatious mansion is no fun, it’s vast and gloomy – it’s a symbol of how Kane can’t see (big message) that he’s misused all his riches and bought himself unhappiness. The mystery of uncovering the meaning of his final word “Rosebud” goes past all investigators and biographers, but is unearthed to us as a key hole into his inner child id.

6. Citizen Kane (1941) – Deep focus, low-angle shots, non-linear narrative, radio music accompaniment, the “documentary” newsreel as story overview, the breakfast scene montage which depicts an entire marriage in five vignettes, the matte shots. “Kane” has been hailed so long as such a landmark in technical filmmaking that it has overshadowed the fact that it contains one of life’s most profound messages: How to not be unhappy like Kane. In addition to directing, Orson Welles is Charles Foster Kane in this thinly veiled exposé of mogul William Randolph Hearst. Charles is given away by his poor parents to a rich surrogate father, grows up into an idealistic young man who starts a newspaper, ebulliently expands his media to nationwide syndication, vainly steps up into political ambition, and builds himself the mother of all mansions. Except the ostentatious mansion is no fun, it’s vast and gloomy – it’s a symbol of how Kane can’t see (big message) that he’s misused all his riches and bought himself unhappiness. The mystery of uncovering the meaning of his final word “Rosebud” goes past all investigators and biographers, but is unearthed to us as a key hole into his inner child id.

7. No Country for Old Men (2007) – For all those people who couldn’t grasp the ending it’s this: Tommy Lee Jones’ Sheriff Bell is disillusioned that he never found God in old age and that retirement before professional closure on his last case with indefinitely haunt him. Then there’s the matter of the satchel that caused the killing spree, the film never says outright who ended up with it, but the answer is right there: Who would give a ten-year old boy a hundred dollar bill (following the car accident), if you didn’t have $2 million to spare? Long after the film’s events, serial killer Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem) will spend the rest of his life attracting violence wherever he goes. It’s part of his chiseled and engraved nature. Just as it was written in Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin) that drinking and cheating on his wife is his engraved nature. The paradox of fatalism and predestination makes this perfectly shot and structured Coen Brothers’ film their magnum opus, and yes, it’s as profound as “Citizen Kane.”

7. No Country for Old Men (2007) – For all those people who couldn’t grasp the ending it’s this: Tommy Lee Jones’ Sheriff Bell is disillusioned that he never found God in old age and that retirement before professional closure on his last case with indefinitely haunt him. Then there’s the matter of the satchel that caused the killing spree, the film never says outright who ended up with it, but the answer is right there: Who would give a ten-year old boy a hundred dollar bill (following the car accident), if you didn’t have $2 million to spare? Long after the film’s events, serial killer Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem) will spend the rest of his life attracting violence wherever he goes. It’s part of his chiseled and engraved nature. Just as it was written in Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin) that drinking and cheating on his wife is his engraved nature. The paradox of fatalism and predestination makes this perfectly shot and structured Coen Brothers’ film their magnum opus, and yes, it’s as profound as “Citizen Kane.”

8. Aguirre the Wrath of God (1972, Germany) – The prologue is a riddle itself possibly not fully comprehended until the end: “After the conquest and plundering of the Inca empire by Spain, the Indians invented the legend of El Dorado, a land of gold, located in the swamps of the Amazon headwaters. A large expedition of Spanish adventurers, led by Gonzalo Pizzaro, set off from the Peruvian highlands in late 1560. The only document to survive from this lost expedition is the diary of the monk Gaspar de Carvajal.” Werner Herzog’s Amazon journey was the hardest film there ever has been made (I’d rather have joined the “Apocalypse Now” shoot), so remote and cut-off from typical filming locations, you won’t see anything like it ever again. Klaus Kinski, that bubbling volcano of a physical presence, is the conquistador Pizzaro who capriciously leads a company of men down a doomed river to find the city of gold, his men getting picked off by unseen Indians in the jungle or by immediate disease. Herzog forsakes conventional plotting to give us a vision of madness and megalomania of a 15th century buccaneer who dreams of the ultimate empire but is blind to the death surrounding him.

8. Aguirre the Wrath of God (1972, Germany) – The prologue is a riddle itself possibly not fully comprehended until the end: “After the conquest and plundering of the Inca empire by Spain, the Indians invented the legend of El Dorado, a land of gold, located in the swamps of the Amazon headwaters. A large expedition of Spanish adventurers, led by Gonzalo Pizzaro, set off from the Peruvian highlands in late 1560. The only document to survive from this lost expedition is the diary of the monk Gaspar de Carvajal.” Werner Herzog’s Amazon journey was the hardest film there ever has been made (I’d rather have joined the “Apocalypse Now” shoot), so remote and cut-off from typical filming locations, you won’t see anything like it ever again. Klaus Kinski, that bubbling volcano of a physical presence, is the conquistador Pizzaro who capriciously leads a company of men down a doomed river to find the city of gold, his men getting picked off by unseen Indians in the jungle or by immediate disease. Herzog forsakes conventional plotting to give us a vision of madness and megalomania of a 15th century buccaneer who dreams of the ultimate empire but is blind to the death surrounding him.

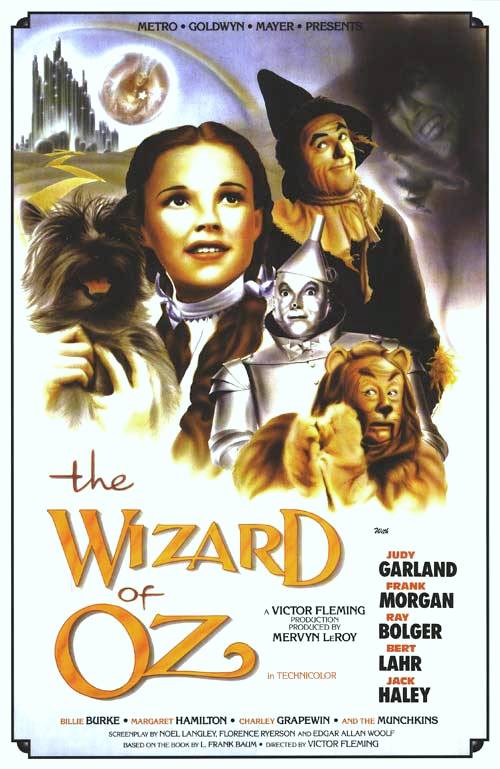

9. The Wizard of Oz (1939) – Worth a million smiles. Honestly this was the most enchanting thing ever if you were young enough when you saw it the first time. Judy Garland’s Dorothy and her dog Toto go on a trek, meet a magician who forecasts the future from a crystal ball, returns home to face a Twister, and crashes in the Land of Oz! Dorothy meets the Scarecrow, the Tin Man and the Cowardly Lion (Ray Bolger, Jack Haley, Bert Lahr). I’m pretty much ecstatic for all of them. And tickled too by the Emerald City and Wicked Witches’ castle, and if there has ever been a road I wanted to skip along it’s on the yellow brick road. The beauty of the original “Oz” is that it’s an exciting parable not “relevant” to anything topical, except to the mysteries of the benign heart. Art direction and costumes are dazzlers. Director Victor Fleming was a feisty pageantry type of filmmaker who did not have to face the kind of bullying studio interference that plague filmmakers today (take Sam Raimi’s “Oz”). MGM felt the Kansas scenes and Garland song was tacky, Fleming argued tersely and won. Always enjoyable and uplifting no matter how many times you’ve seen it.

9. The Wizard of Oz (1939) – Worth a million smiles. Honestly this was the most enchanting thing ever if you were young enough when you saw it the first time. Judy Garland’s Dorothy and her dog Toto go on a trek, meet a magician who forecasts the future from a crystal ball, returns home to face a Twister, and crashes in the Land of Oz! Dorothy meets the Scarecrow, the Tin Man and the Cowardly Lion (Ray Bolger, Jack Haley, Bert Lahr). I’m pretty much ecstatic for all of them. And tickled too by the Emerald City and Wicked Witches’ castle, and if there has ever been a road I wanted to skip along it’s on the yellow brick road. The beauty of the original “Oz” is that it’s an exciting parable not “relevant” to anything topical, except to the mysteries of the benign heart. Art direction and costumes are dazzlers. Director Victor Fleming was a feisty pageantry type of filmmaker who did not have to face the kind of bullying studio interference that plague filmmakers today (take Sam Raimi’s “Oz”). MGM felt the Kansas scenes and Garland song was tacky, Fleming argued tersely and won. Always enjoyable and uplifting no matter how many times you’ve seen it.

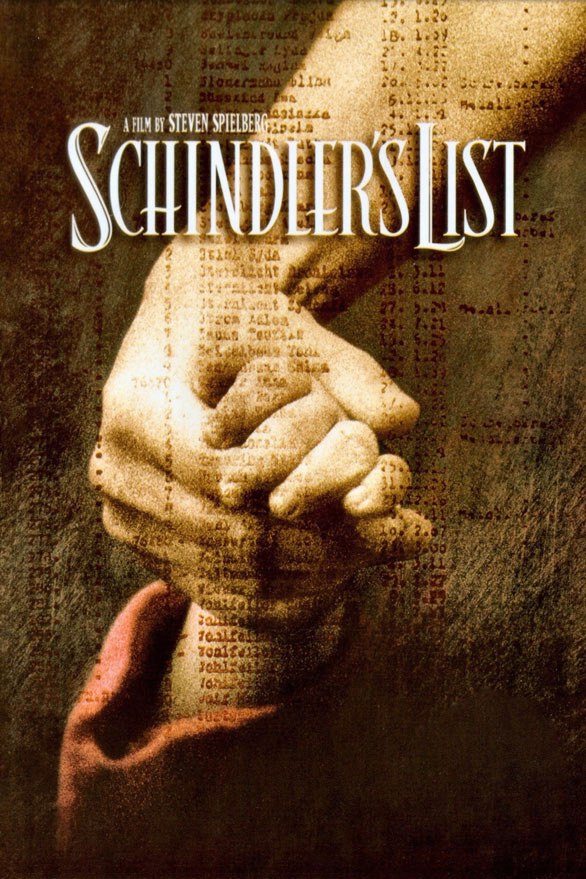

10. Schindler’s List (1993) – I considered choosing a more offbeat and obscure title to gather attention, but Steven Spielberg’s film is too overpowering too ignore. Spielberg transformed public perception of the Holocaust – certainly it was the first big budget film to depict the bloody horrors, the mass genocide, and the hows of the few lucky to get out. Liam Neeson is the enterprising businessman who came to Nazi-occupied Poland to exploit Jews as free labor but then became a humanitarian when he witnessed genocide in Krakow. Ralph Fiennes is the Nazi prison camp commandant Amon Goeth, unblinking in his evil and alliance to National Socialism. Ben Kingsley is Itzhak Stern, the Jewish accountant and Schindler’s right-hand man. Somehow we feel like we meet the 1,100 people too that were saved at the end of the film within its 3 hours and 15 minutes. The black & white is not only essential in establishing an authentic mood, it is a definitive example of what high contrast lighting can do in forcing us to scrutinize the frame for details. Seeing “List” is to understand the darkest hours of human history of the twentieth century and to be empathetically wiser.

10. Schindler’s List (1993) – I considered choosing a more offbeat and obscure title to gather attention, but Steven Spielberg’s film is too overpowering too ignore. Spielberg transformed public perception of the Holocaust – certainly it was the first big budget film to depict the bloody horrors, the mass genocide, and the hows of the few lucky to get out. Liam Neeson is the enterprising businessman who came to Nazi-occupied Poland to exploit Jews as free labor but then became a humanitarian when he witnessed genocide in Krakow. Ralph Fiennes is the Nazi prison camp commandant Amon Goeth, unblinking in his evil and alliance to National Socialism. Ben Kingsley is Itzhak Stern, the Jewish accountant and Schindler’s right-hand man. Somehow we feel like we meet the 1,100 people too that were saved at the end of the film within its 3 hours and 15 minutes. The black & white is not only essential in establishing an authentic mood, it is a definitive example of what high contrast lighting can do in forcing us to scrutinize the frame for details. Seeing “List” is to understand the darkest hours of human history of the twentieth century and to be empathetically wiser.