“I will not allow violence against this house.” – David Sumner

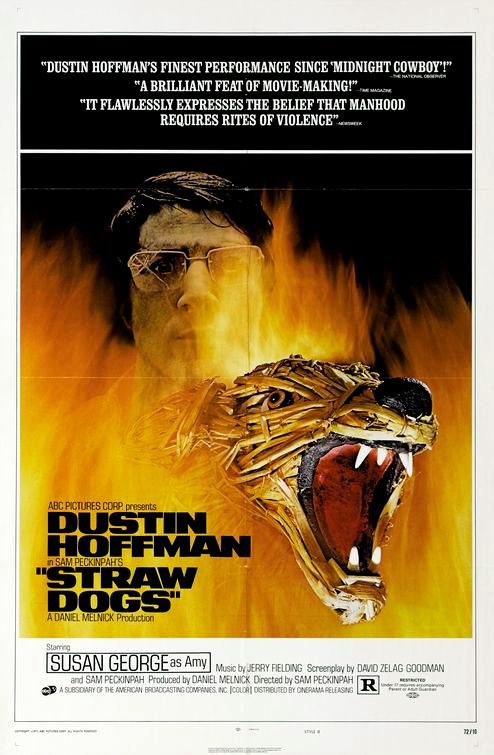

As the debate of violent rage in the psyches of the modern male continuously gets expounded year after year in movies, only one has ever seemed to nail it inside and out. Straw Dogs (1971) was originally rated X in its premiere for extreme violence and a sexual assault, and was banned in the United Kingdom for a number of years. It remains a rough, queasy and unpleasant film to watch and it is easy to imagine how some audiences might be turned off by the film. The film contains gratuitous violence, because it is about gratuitous violence – and how we’re sucked into participating in deplorable actions. It is rather brilliant in what it says about man’s capacity to commit violent acts when provoked by circumstance. By all means, if you’re hooked, see this Sam Peckinpah classic. This was the iconic director’s finest hour, although “The Wild Bunch” (1969) is most often mentioned alongside his name.

Dustin Hoffman plays weakling mathematician David Sumner who relocates with his wife Amy (Susan George) to the rural English countryside. The couple have hired four locals to build a garage and to assist in other renovations of their new home. One of the hired hands, Charlie Venner (Del Henney), had a brief relationship history with Amy and is still obsessed by her. In turn, he is contemptuous towards David, who in his eyes is unmasculine and unworthy.

The four hired hands, customary heavy drinkers, begin harassing the couple lightly by ridiculing David and ogling Amy (flaunting her body at them doesn’t help). The harassment becomes more and more blatant, and it builds to a scene where David’s and Amy’s cat is deliberately harmed. But no blame is directed verbally. Amy calls David a coward because of his inability to stand up and take action. Instead of making sour accusations, David makes feeble attempts to befriend the workers as a way to win favor. But it is simply another demonstration of his ineffectual, unmanly behavior. David’s way of countering the boys is to act smug in his intellectual superiority.

The drama leads to the hotly contested rape scene, one that might go too far for some viewers. David is out duck hunting with a few of the boys, and although this is supposed to be a day of camaraderie for him, he is made into a laughing stock. At home, Amy is overpowered by her ex, the beefy Charlie. Following Charlie, other men become Amy’s violators. The scene is about psychological terror mostly. How will she ever tell her husband? Or can she?

Amy has difficulty with the perpetrators’ presence at a church function later on. Without inquiring about the suddenness of her emotional duress, David agrees to take Amy home early. While driving through a dense fog, they accidentally strike down the town simpleton Henry Niles (David Warner) with their car. Unbeknownst to them, Henry Niles has just strangled a young girl named Janice (Sally Thomsett, who appeared to have a schoolgirl’s crush on Mr. Sumner).

A vigilante mob commences to hunt for Niles and his whereabouts are traced to David’s home. David deduces that the mob will beat and kill Henry Niles if they get to him. Janice’s father is a drunkard who leads the mob David’s home, and with the aid of the four handymen they take the house under siege. They are spurred by alcohol, by the fever of the mob mentality, by the debauchery of their recent experiences there. Different weather conditions might have steered them away, but the frigid cold and fog somehow keeps everyone there in joined participation. One would not trot off in the dark alone, he would rather remain amongst hostile company.

A vigilante mob commences to hunt for Niles and his whereabouts are traced to David’s home. David deduces that the mob will beat and kill Henry Niles if they get to him. Janice’s father is a drunkard who leads the mob David’s home, and with the aid of the four handymen they take the house under siege. They are spurred by alcohol, by the fever of the mob mentality, by the debauchery of their recent experiences there. Different weather conditions might have steered them away, but the frigid cold and fog somehow keeps everyone there in joined participation. One would not trot off in the dark alone, he would rather remain amongst hostile company.

The final half hour is as intense and relentless as any sequence of film as I have ever seen. The antagonists hurl rocks through the windows, toss rats into their house and set portions of the house on fire. As the invaders circle the house in a violent frenzy, David takes measure by jamming the doors, turning on the outdoor lights and, as part of pragmatic manhood, preps house-made weapons to use in his defense – including a bear trap.

Amy pleads with David to give up Henry Niles to the mob, and Hoffman’s anger escalates due to his wife’s uncompassionate stance. This is where he slaps her. But by the way he slaps her it has a different intonation – as if revealing that he doesn’t really love/respect her (this deepens the abyss of the film’s moral complexity). David, it could be interpreted, is fending off the home invaders because it is an insult to his manhood. A man’s home is his castle. But he has lost his wife’s everlasting love in exchange. If she had remained a “perfect” woman up until that moment, would David have just listened to Amy from the start? Or compromised with her?

After a first death, there is no turning back for the vigilantes – they must break in and kill David and the others he is harboring. The results are inexorable acts of carnage punctuated by one awkward moment – two members of the mob vie for David’s wife. In an off-kilter close-up, Hoffman is beguiled but clued into their likely motivations at the same time.

After a first death, there is no turning back for the vigilantes – they must break in and kill David and the others he is harboring. The results are inexorable acts of carnage punctuated by one awkward moment – two members of the mob vie for David’s wife. In an off-kilter close-up, Hoffman is beguiled but clued into their likely motivations at the same time.

Peckinpah’s editing in the final act is masterful, composing a series of rapidly increasing juxtaposition during the gruesome, no holds barred fighting. The action, the back-and-forth cutting and sliding camera movements of the house interior and exterior, seem to let the viewer know exactly how, and where, the characters are positioned and in what they are engaged in moment to moment. The moody and dense music score is by Jerry Fielding, the multi-layered screenplay is by David Zelag Goodman and Peckinpah, and the foggy scenery was captured by cinematographer John Coquillon.

Hoffman’s performance is among the best of his career – he’s timid but has a violent undercurrent simmering towards eruption. Like his opponents, he is using violence to prove his manhood. Hoffman’s character is more sensible than the brutes, since he is the most conscious in ability to weigh the costs of his actions. Only Hoffman though can make excuse of himself for killing in the name of self-defense. Blistering and incendiary, “Straw Dogs” is a vision that sears into your perspective of the whole world, and troubles you forever.

118 Minutes. Rated R.

Film Cousins: “The Wild Bunch” (1969); “Deliverance” (1972); “Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia” (1974); “A History of Violence” (2005).