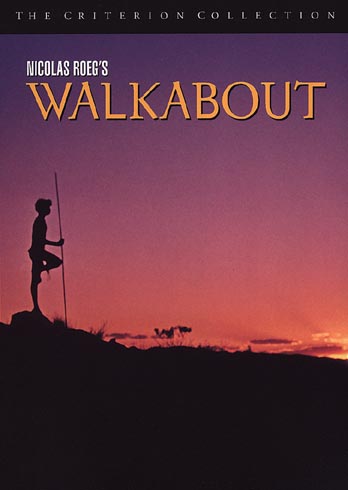

“In Australia when an Aborigine man-child reaches sixteen, he is sent out into the land. For months he must live from it. Sleep on it. Eat of its fruit and flesh. Stay alive. Even if means killing his fellow creatures. The Aborigines call it the Walkabout. This is the story of a Walkabout.” – Prologue

One of the ten best films ever made. Walkabout (1971) features two city children lost in the Outback, luckily saved by an Aborigine boy who is on his yearlong exodus to claim his manhood. It begins weirdly with abstract images of modern life that are brilliantly bookended in the conclusion. Stick around long enough and you will catch some of the most beautiful imagery ever captured. Here’s a film that was filmed and created in a particular time and place that will never be duplicated again. The current “Life of Pi” is the closest any film in ages that has truly been able to compare on a transcendent level, but they are more similar in theme than in texture. This 1971 film is its own singular touchstone.

The film is just barely inappropriate for young children, but then again, see for yourself first and then decide when you want to share it with your brood. Mostly, the first dramatic scene of the film in the desert is what will scare or bewilder younger viewers. Scene  description: The father has taken his two young children to the desert. It is suggested in a brief leering shot that the father is ashamedly attracted to his daughter. Misses his children with his revolver, sets his car ablaze, and uses the final bullet to do away with himself. The children, unscathed, run into the wilderness to be lost. All filmed in such a matter of fact way.

description: The father has taken his two young children to the desert. It is suggested in a brief leering shot that the father is ashamedly attracted to his daughter. Misses his children with his revolver, sets his car ablaze, and uses the final bullet to do away with himself. The children, unscathed, run into the wilderness to be lost. All filmed in such a matter of fact way.

They do what any city children would do. They pant for food, water and shelter in a petulantly impatient way. Over the course of time, lost indefinitely, they will require less and less. That is an interpretive meaning to the word “adaptation,” is it not?

Jenny Agutter is the nameless beautiful teen girl on the transition to womanhood, and Lucien John as her little brother who is innocent and has only a limited cognition of their predicament. The boy craves food and water, but once fulfilled, he yearns to kill boredom. The arrival of David Gumpilil (an indigenous member who became an unlikely movie actor for the next 30 years in Australia productions) as the Aborigine man-child dilutes the boredom. “I expect we’re the first white people he’s seen,” the young girl observes.

Jenny Agutter is the nameless beautiful teen girl on the transition to womanhood, and Lucien John as her little brother who is innocent and has only a limited cognition of their predicament. The boy craves food and water, but once fulfilled, he yearns to kill boredom. The arrival of David Gumpilil (an indigenous member who became an unlikely movie actor for the next 30 years in Australia productions) as the Aborigine man-child dilutes the boredom. “I expect we’re the first white people he’s seen,” the young girl observes.

The Aborigine boy is fascinated by her, beyond terms of conventional communication. Of course, without a shared language there will be dramatic miscommunication between them. The young girl wants the Aborigine boy to guide them back to the city, or an outpost with white people who can rescue them.

The Aborigine boy wants companionship, love, to share his adventures, to be a teacher and sage. Two white children consensually become his students. The Aborigine boy, smitten with the girl in particular, enacts a mating ritual which is unfamiliar to the girl. Heartbreak and rejection is devastating in all cultures universally, it’s no different in the Outback as it is at an inner city high school. The Aborigine boy is hard on himself because since his mating ritual is rejected, he sees himself as a failure. Not unlike most 17-year old boys who fail at first love (I will attest myself, too).

The return to civilization is emphasized less, the pleasures of the journey reveled. Of course the two protagonists have to eventually return home – the idea of returning home is part of many of our genetic instinct. They are from the city. They have family. But survival in nature becomes a game we subconsciously strive to master, perhaps it is a lifestyle for some inclined. A conduit to spiritual freedom. I haven’t always myself known who I am until I am stripped free from modern devices and conveniences to be given infinite space in the wilderness to think.

The return to civilization is emphasized less, the pleasures of the journey reveled. Of course the two protagonists have to eventually return home – the idea of returning home is part of many of our genetic instinct. They are from the city. They have family. But survival in nature becomes a game we subconsciously strive to master, perhaps it is a lifestyle for some inclined. A conduit to spiritual freedom. I haven’t always myself known who I am until I am stripped free from modern devices and conveniences to be given infinite space in the wilderness to think.

There are animals in the Outback (as well as limitless animals, insects and exotic organisms photographed in this film, and yes, kangaroos!). Hunted by the Aboriginals for food and survival. Hunted by white men selfishly for sport. We see those contrasts, as well as the contrasts of how food is prepared and served in wilderness, and how it is chopped and packaged back in modern society. The girl and boy will have advanced thought processes later in life built from this lost experience, because they have lived the pyramid from inside and out. They have embedded knowledge that is exclusive to them.

There are animals in the Outback (as well as limitless animals, insects and exotic organisms photographed in this film, and yes, kangaroos!). Hunted by the Aboriginals for food and survival. Hunted by white men selfishly for sport. We see those contrasts, as well as the contrasts of how food is prepared and served in wilderness, and how it is chopped and packaged back in modern society. The girl and boy will have advanced thought processes later in life built from this lost experience, because they have lived the pyramid from inside and out. They have embedded knowledge that is exclusive to them.

We are molded by our surroundings, conditioned and programmed. Force me to a few days in the Outback with no experience, I am impotent and desperate. Give me a guide to teach me and grant me the time to adapt over several weeks, I will persevere and become fond of my new lifestyle.

The girl is seen years later, grown up in a conventional city life, but one senses she currently feels spiritually trapped by conventional living and hungers for her past when she roughed it in nature with an adventurer as a guide. Are we all able to return to our past with the same purity as originally felt? Life’s greatest moments are lamentably unrepeatable.

The girl is seen years later, grown up in a conventional city life, but one senses she currently feels spiritually trapped by conventional living and hungers for her past when she roughed it in nature with an adventurer as a guide. Are we all able to return to our past with the same purity as originally felt? Life’s greatest moments are lamentably unrepeatable.

Extraordinary cinematography was done by director Nicolas Roeg himself. Roeg’s career has been criminally unrecognized. In brief, he made three masterpieces that defy orthodox genre description: “Walkabout” for its landscape imagery and human spiritual themes; the horror film set in Venice called “Don’t Look Now” (1973) which is for anybody who loved “The Sixth Sense;” and the stunningly weird alien on Earth saga “The Man Who Fell to Earth” (1976) which transforms into an allegory of sex addiction and alcoholism. The film most people have nonchalantly seen by him is the children’s film “The Witches” (1990), the drawing appeal however were fans of author Roald Dahl.

Spellbinding is not a word I’ve used a dozen times to describe a film, but I could watch “Walkabout” with no sound on and be spellbound.

100 Minutes. Rated G.

Film Cousins: “The Man Who Fell to Earth” (1976); “Spring Summer Fall Winter… And Spring” (2003, South Korea); “Into the Wild” (2007); “Life of Pi” (2012).