As our hearts go out to the people of Japan in the tsunami aftermath, perhaps some of you wish that you had a deeper understanding of Japanese culture. You realize there has been an unintended neglect by you of the peoples’ way of tradition and history, and now you want to turn that around and know more. As a sobering amends you want to see a Japanese film but you don’t know which one. I have chosen twelve essential films that I list in order of descending preference.

Woman in the Dunes (1964) – One of the greatest of all films, too. “Lawrence of Arabia” is ubiquitously considered the ultimate sand dunes film but it doesn’t hold a candle to this Hiroshi Teshigahara film. Why isn’t as known? Obvious, it is ethnocentric favoritism towards American film. Imagine “The Truman Show” without cameras but observers perched atop sand dunes, with people lodged in the dunes like inhabitants of an ant colony. The woman needs a companion so the sovereign rulers who reside atop in the village trick a man (Eiji Okada) into the pit for a hospice night and then permanently remove the ladder. The man,  desperate for freedom, attempts to climb and scale the wall of sand. The black & white sandstorm cinematography with cascading soil is unforgettable imagery. The man cannot get out, at least not until he devises an ingenious escape plan, and so he has the choice to argue and battle with a woman a little cuckoo from long term isolation or give in to a woman who offers her body and her companionship. During the day they have to constantly dig dirt in daylight so the dunes don’t bury the house at the bottom of the pit. The message is learning to live content in an impossible situation. There’s a word for this film not commonly applied: Mesmerizing.

desperate for freedom, attempts to climb and scale the wall of sand. The black & white sandstorm cinematography with cascading soil is unforgettable imagery. The man cannot get out, at least not until he devises an ingenious escape plan, and so he has the choice to argue and battle with a woman a little cuckoo from long term isolation or give in to a woman who offers her body and her companionship. During the day they have to constantly dig dirt in daylight so the dunes don’t bury the house at the bottom of the pit. The message is learning to live content in an impossible situation. There’s a word for this film not commonly applied: Mesmerizing.

Tokyo Story (1953) – I know what some of you will think, “Why would Sean Chavel recommend a film that’s so goddamn slow-moving?” Because you will end up needing this film more than it seems in the beginning. This is a film that everyone should see once in their lifetime and while the exoticism of its time period will appear daunting, eventually it strikes a universal cord and will become 100% felt. Occupying the center is an elderly couple from a remote village who come to the big city to visit their various children who treat them to a few hours here and there to excursions, but largely  dismiss them because of occupational and community duties. What the children fail to see is that this could be the last time their parents ever visit Tokyo and could be the last time they see both parents together. Anybody with a degree of sensitivity and yet a history with parents you have taken for granted should see this and become aware of the need to keep closer connections with those who raised you. Peripherally you see the everyday life of Tokyo in a looking glass into the middle 20th century.

dismiss them because of occupational and community duties. What the children fail to see is that this could be the last time their parents ever visit Tokyo and could be the last time they see both parents together. Anybody with a degree of sensitivity and yet a history with parents you have taken for granted should see this and become aware of the need to keep closer connections with those who raised you. Peripherally you see the everyday life of Tokyo in a looking glass into the middle 20th century.

Spirited Away(2002) – Just about the most enchanting of all animated films, and people often forget that it actually won the Oscar for Best Animated film – remarkable for an import. Please note it has been dubbed into English by Walt Disney Studios, and by doing so, it has won many hearts in America. After entering a gateway that leads into a fantastical new world, a bratty girl loses her parents when they turn into pigs after an episode of gluttony. Encircling the land are the strangest creatures ever to blow up from an animator’s imagination. A sorceress governs a towering palace and with prid e operates a magnificent bathhouse. Our girl Chihiro is without a doubt a helpless twit, but her journey requires her to adapt to her environment and grow up. To do this she must find a job and a place in the tower, do service, and trade to have her parents back. Portions of the film explore the connection between the spirit world and reincarnation, as well the physiological myth on the link between corporeal body and the soul. As miracles go, this out-wonders “Alice in Wonderland.”

e operates a magnificent bathhouse. Our girl Chihiro is without a doubt a helpless twit, but her journey requires her to adapt to her environment and grow up. To do this she must find a job and a place in the tower, do service, and trade to have her parents back. Portions of the film explore the connection between the spirit world and reincarnation, as well the physiological myth on the link between corporeal body and the soul. As miracles go, this out-wonders “Alice in Wonderland.”

Rashomon(1950) – Intellectually stimulating without being a mind-sore. Akira Kurosawa’s film of 19th century feudal Japan unfolds in four perspectives: In the woods, a bandit rapes a woman in front of her husband, and soon after, he is killed and the bandit  is caught. In flashbacks, we get radically different perspectives from the perpetrator, the husband, the wife, and those that witnessed. What is learned is that one is willing to lie in order to maintain the appearance of dignity. Anybody can be a coward to the truth in order to spin the story their self-serving way. In cynical circumstances, men with noble intentions do what they can to act with kindness not because it will resolve everything but because a reminder is needed that the world sometimes needs relief just when hardships are at their most unbearable. 88 scant but efficient minutes, this becomes one of the supreme morality films.

is caught. In flashbacks, we get radically different perspectives from the perpetrator, the husband, the wife, and those that witnessed. What is learned is that one is willing to lie in order to maintain the appearance of dignity. Anybody can be a coward to the truth in order to spin the story their self-serving way. In cynical circumstances, men with noble intentions do what they can to act with kindness not because it will resolve everything but because a reminder is needed that the world sometimes needs relief just when hardships are at their most unbearable. 88 scant but efficient minutes, this becomes one of the supreme morality films.

Departures (2009) – One of the key films that changed my life. Putting aside traditional film criticism, I will tell you I grew up with a mother into emotional grieving – a mother that would carry on without dignity when dealing with the passing of a loved one. Ever witnessed how high-strung, overly pious American women can wail and cry their eyes out? Peace and resolve is something that the Japanese possess in this film, so instead of them selfishly calling attention to overbearing grieving they honor the memory of the dead. Isn’t it true in due fair contemplation that your loved ones flourish as much in your heart as well as in your mind? Despondent over his failed career as a cellist, Daigo moves himself and his wife Mika (Ryoko Hirosue) back to small town of Yamagata where he grew up and takes over his late mother’s house. With a shortage of available jobs, Daigo jumps at an opening at an unnamed company offering few hours, lots of money. Daigo agreeably accepts the job as encoffiner before he knows what it actually means. Then with grace, at the expense of losing friends and losing respect from his wife, he pursues a full nokanshi title whose purpose is to perform ceremonial washing of corpses before their burial. Despite the “death” theme, everything is deep and everything is soothing.

well as in your mind? Despondent over his failed career as a cellist, Daigo moves himself and his wife Mika (Ryoko Hirosue) back to small town of Yamagata where he grew up and takes over his late mother’s house. With a shortage of available jobs, Daigo jumps at an opening at an unnamed company offering few hours, lots of money. Daigo agreeably accepts the job as encoffiner before he knows what it actually means. Then with grace, at the expense of losing friends and losing respect from his wife, he pursues a full nokanshi title whose purpose is to perform ceremonial washing of corpses before their burial. Despite the “death” theme, everything is deep and everything is soothing.

Audition (1999) –The only film to truly give me nightmares in my adult life and they lasted for months. The obvious question is why would any night terrors be worth it, but the truth is I am so psychologically fascinated by it. The first hour has some lithe and jaunty tones to it that lead you to think it is a comedy or a bittersweet middle-aged romance drama, not the horror film it is, except there are subtle clues that you’re in for some transgression. Shigeharu Aoyama (Ryo Ishibashi), a middle-aged widower who lost his wife to an illness seven years  prior, is urged by his 17-year-old son Shigehiko (Tetsu Sawaki) to search for a new wife. Colleague Yoshikawa (Jun Kunimara) suggests to him to hold a mock audition so he can meet an actress not to hire but to string along, butter up, and romance her into becoming his wife. This is a classically legitimate-looking audition of thirty women. Shigeharu has time to brief the applications beforehand and is instantly smitten by 24-year old Asami (Eihi Shiina). The scrupulous Yoshikawa, a real power player, immediately senses there is something strange and off-putting about Asami. But nothing can convince Shigeharu that this girl is anything less than perfect and following the audition they begin dating. The key climactic flashback of the film intersperses memories, dreams and hallucinations, a message from his dead wife, not to mention intermixed projections of who Asami is and who he thinks she is. Shigeharu ignores crucial information that should have driven him to follow-up questions. “When I was little, my parents got a divorce. I was sent to my uncle’s house. That was a terrible place. I only remember being abused. I have many scars… I did nothing in a dark room every day,” Asami reveals. The revolting aspects are hinted scantily throughout but it is not until the last twenty minutes where the tingles turn to extreme repulsiveness. The tables are turned on viewer’s expectations. Is this a male or female victim horror show? Gradually Takashi Miike’s genre-bending horror film gathers power by making the implausible look plausible. This isn’t a selection that reflects the pride of Japanese people, but I can’t lie, I admire it too much. An exception that I wouldn’t call essential for all of you.

prior, is urged by his 17-year-old son Shigehiko (Tetsu Sawaki) to search for a new wife. Colleague Yoshikawa (Jun Kunimara) suggests to him to hold a mock audition so he can meet an actress not to hire but to string along, butter up, and romance her into becoming his wife. This is a classically legitimate-looking audition of thirty women. Shigeharu has time to brief the applications beforehand and is instantly smitten by 24-year old Asami (Eihi Shiina). The scrupulous Yoshikawa, a real power player, immediately senses there is something strange and off-putting about Asami. But nothing can convince Shigeharu that this girl is anything less than perfect and following the audition they begin dating. The key climactic flashback of the film intersperses memories, dreams and hallucinations, a message from his dead wife, not to mention intermixed projections of who Asami is and who he thinks she is. Shigeharu ignores crucial information that should have driven him to follow-up questions. “When I was little, my parents got a divorce. I was sent to my uncle’s house. That was a terrible place. I only remember being abused. I have many scars… I did nothing in a dark room every day,” Asami reveals. The revolting aspects are hinted scantily throughout but it is not until the last twenty minutes where the tingles turn to extreme repulsiveness. The tables are turned on viewer’s expectations. Is this a male or female victim horror show? Gradually Takashi Miike’s genre-bending horror film gathers power by making the implausible look plausible. This isn’t a selection that reflects the pride of Japanese people, but I can’t lie, I admire it too much. An exception that I wouldn’t call essential for all of you.

Ikiru (1952) – For thirty years Mr. Watanabe (Takashi Shimura) toils as a bureaucrat at Tokyo City Hall without ever having really contributed to mankind or, on a smaller scale, his community. He is not one of importance within his own community. He has been an undistinguished government cog – not much of a humanitarian – just a man defined by endless filing cabinets and documents that pile up on top of each other. But now he has learned he is dying of cancer, and while he is conjecturing the meaning of life, he meets a stranger that takes him out for a wild night out in the red light district.  This mid-section of the movie might put you in a pausing state of grace, as you might go, “Wow, the night life looks really alive and vivacious for its time.” As the flight of excitement wears down, Mr. Watanabe reflects on the idea that he wants to leave some kind of imprint on the world before he expires. The good deed becomes… a park. The need for a park as a social utility in the one particular neighborhood surmounts to a great significance. The old man does everything he can, even through sickness, to try to pull this off. You can hardly anticipate that a shot of snow falling on an old man could be so powerful. Damn worth the patience.

This mid-section of the movie might put you in a pausing state of grace, as you might go, “Wow, the night life looks really alive and vivacious for its time.” As the flight of excitement wears down, Mr. Watanabe reflects on the idea that he wants to leave some kind of imprint on the world before he expires. The good deed becomes… a park. The need for a park as a social utility in the one particular neighborhood surmounts to a great significance. The old man does everything he can, even through sickness, to try to pull this off. You can hardly anticipate that a shot of snow falling on an old man could be so powerful. Damn worth the patience.

Late Spring (1949) – Just as slow and meditative as Ozu’s “Tokyo Story,” although he moves his camera around more often than usual. The central characters are domesticated in traditional Japanese houses with adherence to old-fashioned values, with maybe a few westernized flourishes. Noriko (Setsuko Hara) is 27 years old and unmarried because she  feels her duty is to stay home and care for her widowed father Professor Shukichi Somiya (Chishu Ryu). But her father and her aunt want her to marry because it is the expected life stage to go onto. It’s very possible, if you look back after the film is over, that Noriko’s craziest feelings of desire for a man was likely for Hattori (Jun Usami) but such feelings were immediately brushed aside because it was no surprise he was already engaged to somebody else. Noriko’s idea of perfect happiness is with her father. An early scene has the father bark “Make tea” without any cordial etiquette is his voice. Later on, the father makes tea for his daughter and her guest – we sense this is unlikely of him yet somehow we see that he cares about his daughter’s social prospects when they do matter. The father is not afraid of being alone, and as respected as he is, doesn’t fear he will be isolated by seeing his daughter off. But Noriko sees that if she’s gone there will be nobody to wipe down his desk, make him rice, wash his clothes and all the other domestic necessities. The father will be lost without her, at least Noriko sees this. The aunt proposes an arranged marriage for Noriko to a prosperous businessman who looks like American actor Gary Cooper. Noriko concedes that the Gary Cooper lookalike is a handsome man. A concluding decision is made surrounding the father’s one big lie, or just a fib, you decide. Every decisive act Noriko makes owes to her commitment to family loyalty. This is a long-ago former generation but ultimately you very much understand these characters and relate to what family means to them.

feels her duty is to stay home and care for her widowed father Professor Shukichi Somiya (Chishu Ryu). But her father and her aunt want her to marry because it is the expected life stage to go onto. It’s very possible, if you look back after the film is over, that Noriko’s craziest feelings of desire for a man was likely for Hattori (Jun Usami) but such feelings were immediately brushed aside because it was no surprise he was already engaged to somebody else. Noriko’s idea of perfect happiness is with her father. An early scene has the father bark “Make tea” without any cordial etiquette is his voice. Later on, the father makes tea for his daughter and her guest – we sense this is unlikely of him yet somehow we see that he cares about his daughter’s social prospects when they do matter. The father is not afraid of being alone, and as respected as he is, doesn’t fear he will be isolated by seeing his daughter off. But Noriko sees that if she’s gone there will be nobody to wipe down his desk, make him rice, wash his clothes and all the other domestic necessities. The father will be lost without her, at least Noriko sees this. The aunt proposes an arranged marriage for Noriko to a prosperous businessman who looks like American actor Gary Cooper. Noriko concedes that the Gary Cooper lookalike is a handsome man. A concluding decision is made surrounding the father’s one big lie, or just a fib, you decide. Every decisive act Noriko makes owes to her commitment to family loyalty. This is a long-ago former generation but ultimately you very much understand these characters and relate to what family means to them.

Nobody Knows (2005) – It’s like the realistic version of “Home Alone,” in fact, it’s based on a true story. In contemporary Japan, four kids ranging from four to twelve years old, are abandoned by their mother as she chases after another man. 12-year old Akira (Yagira Yuya, the youngest actor to win Best Actor at the Cannes Film Festival) is  delegated into the paternal role, rationalizing remaining funds and bartering with whatever items of value that have an estimate. His apartment neighbors are ignorant of the children’s situation, and since these are confused children, they think it’s best to hide from them their predicament. Akira appoints himself hunter, gatherer, scavenger while leaving the other three at home with a rule to be quiet. Akira meets outside friends, tries to fit in with pick-up park baseball, and develops his first crush for a neighborhood girl. But the saga of neglect goes down in just the way as you would honestly think it would go down. These autonomous children are no cry babies though.

delegated into the paternal role, rationalizing remaining funds and bartering with whatever items of value that have an estimate. His apartment neighbors are ignorant of the children’s situation, and since these are confused children, they think it’s best to hide from them their predicament. Akira appoints himself hunter, gatherer, scavenger while leaving the other three at home with a rule to be quiet. Akira meets outside friends, tries to fit in with pick-up park baseball, and develops his first crush for a neighborhood girl. But the saga of neglect goes down in just the way as you would honestly think it would go down. These autonomous children are no cry babies though.

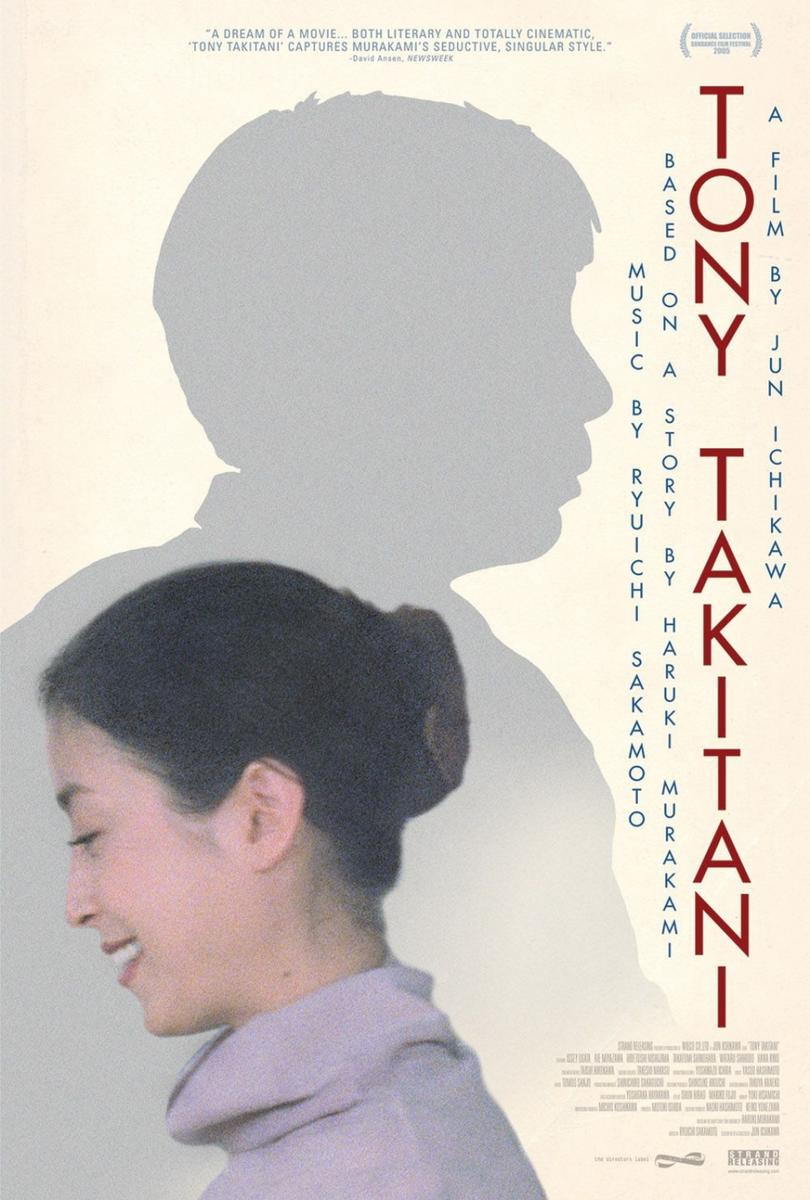

Tony Takitani (2004) – 75 minutes long, told entirely in “ballad poem.” It begins with Tony being born, his mother dying. Thus it unfolds: We see his entire life before him, in objective pan shots, told thru music and narration, told in terse scenes of quiet dialogue, told occasionally in still and steady shots during the most important moments. Tony is a  very lonely person that got used to be alone at a very early age – he was designed that way, like God’s intended hermit. It’s sad, but you want to see Tony be better socially, and happy. It’s not that he himself wants to be alone. He excels at art and architectural design throughout his whole life. He makes himself rich, and in doing so, he can provide a comfortable life for a woman to be his wife. Yet he is the not the kind of man that will ever be lucky enough to fall in love. He is too squared for that. But he does meet a woman, and by relative standards, she is very attractive. He gets used to not being alone, in having her by his side. For the first time, he fears being alone and gets anxious when she’s not around. The new wife has one bad habit: She loves shopping for designer clothes. She says it fills up the emptiness inside. She loves Tony, and it’s not like she does it out of boredom, but it’s compulsive behavior. Like karma, the complaint to “Stop Shopping!” unravels everything that Tony has ever done to acquire his long-awaited happiness.

very lonely person that got used to be alone at a very early age – he was designed that way, like God’s intended hermit. It’s sad, but you want to see Tony be better socially, and happy. It’s not that he himself wants to be alone. He excels at art and architectural design throughout his whole life. He makes himself rich, and in doing so, he can provide a comfortable life for a woman to be his wife. Yet he is the not the kind of man that will ever be lucky enough to fall in love. He is too squared for that. But he does meet a woman, and by relative standards, she is very attractive. He gets used to not being alone, in having her by his side. For the first time, he fears being alone and gets anxious when she’s not around. The new wife has one bad habit: She loves shopping for designer clothes. She says it fills up the emptiness inside. She loves Tony, and it’s not like she does it out of boredom, but it’s compulsive behavior. Like karma, the complaint to “Stop Shopping!” unravels everything that Tony has ever done to acquire his long-awaited happiness.

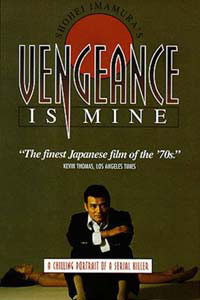

Vengeance is Mine (1979) – It’s a crime story entailing the long pursuit of cops on the trail of a killer (Ken Ogata), and the movie is from the killer’s POV, and what a socially maladjusted brute he is. Yet long after you’ve turned it off what you reflect upon is the portrait of low-class trash in Japan. It’s natural to always uphold fine Japanese traditions  in the cinema but you can’t appreciate that fully until you understand that, just like nearly anywhere, there will exist in society a subculture of outcasts and rejects. Fascinating yet demanding because it has a sliding-scale time narrative which requires you to create your own continuity. On this 78-day spree in 1964 there were murders, impersonations, deceptions and swindles. It’s a skank he meets that lets him hide out, and together, they’re like scampering mice huddling together. Shocking? The first murders are most explicit in the film. But the other aspects of the film (sex, nudity, bad hygiene) gets more explicit as it goes on.

in the cinema but you can’t appreciate that fully until you understand that, just like nearly anywhere, there will exist in society a subculture of outcasts and rejects. Fascinating yet demanding because it has a sliding-scale time narrative which requires you to create your own continuity. On this 78-day spree in 1964 there were murders, impersonations, deceptions and swindles. It’s a skank he meets that lets him hide out, and together, they’re like scampering mice huddling together. Shocking? The first murders are most explicit in the film. But the other aspects of the film (sex, nudity, bad hygiene) gets more explicit as it goes on.

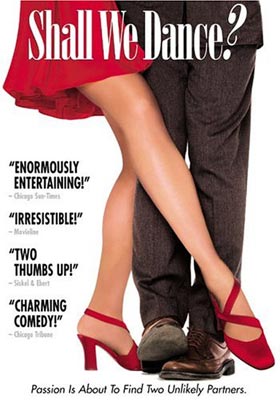

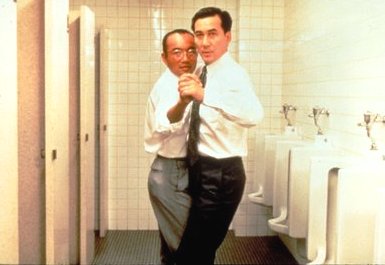

Shall We Dance? (1996) – “It’s a British sport after all,” one laments after being disqualified in a dance tournament. Dance is an embarrassment for most Japanese men but there is a commentary that there can be a secret wonderful joy found in ballroom dance. The middle-aged man Shohei (Koji Yakusyo) is a salary-man with a well-behaved  family at home, but despite the coziness, he feels bland and unhappy. While commuting home on the train he peers up night after night at a dance studio with his eyes locked on an instructor. He gets off the train one night and decides to sign up for lessons which will require him to lie to his wife about working late evenings. Unexpectedly, there are other uncoordinated men that are all two left feet that will take the class. Shohei gets dared by the instructor he was smitten with and so proceeds to take the classes to their fullest extent so he can enter a dance tournament. This isn’t a mistress, but dance becomes a second love. Ultimately, it’s a feel-good life-embracing tale.

family at home, but despite the coziness, he feels bland and unhappy. While commuting home on the train he peers up night after night at a dance studio with his eyes locked on an instructor. He gets off the train one night and decides to sign up for lessons which will require him to lie to his wife about working late evenings. Unexpectedly, there are other uncoordinated men that are all two left feet that will take the class. Shohei gets dared by the instructor he was smitten with and so proceeds to take the classes to their fullest extent so he can enter a dance tournament. This isn’t a mistress, but dance becomes a second love. Ultimately, it’s a feel-good life-embracing tale.