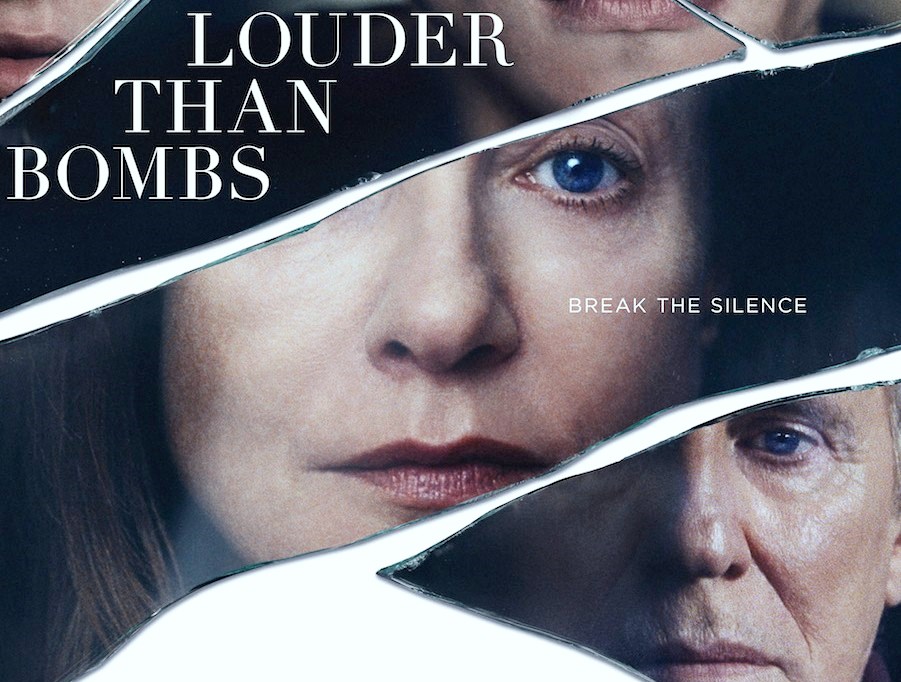

This American character study and meditation on a family’s grief is by a skilled and thoughtful Norwegian filmmaker, but it doesn’t work. Louder Than Bombs opens on false notes, with Jesse Eisenberg fetching food for his wife who has just given birth. Doesn’t this movie know that in real life a nurse would be checking in at least every hour to offer (or deny) food or hydration based on the mother’s condition? Doesn’t it appear obvious, to anyone but the makers of this movie, that full color in her face actress Megan Ketch looks nothing like a woman who has just given birth? But more than any of that, it’s missing the vicarious euphoria a father shares with the woman who has just pushed out a baby. He’s unmoved, but really it’s Eisenberg playing yet another one of his colder than colder characters that couldn’t possibly be bothered by a new addition to his life. When he is down the hospital corridors looking for a cafe or vending machine to grab food for his wife, he runs into an ex-flame. This is the movie’s strained idea for character conflict, you see, the bogus notion that he’s using this exact moment to realize he’d prefer to back away from fatherhood and marital commitment for the promise of something else.

There’s a lot of false notes that stymie this movie even when it gets onto its’ real subject of a family in quiet turmoil and suburban malaise. Everyone here is trying, but I’m not sure it’s to avail. Gabriel Byrne is the sincere if clammed up father trying to fiddle back into his distant sons’ lives, portrayed by Eisenberg and Devin Druid. The iciness is laid on so thick, you’d think Eisenberg had more Asperger’s affliction than his famous turn as Mark Zuckerberg, and Druid is playing one of those withdrawn violent videogame addicts who is so inactive that you just want to toss him into a track and field scene at his high school. Things are a little seamy, for potentially good dramatic measure, when we learn Byrne is having an affair with Amy Ryan, who is Druid’s school teacher. But not enough is made of that.

It’s been a few years, but these three males are still torn up, in their quiet and bottled up way, by the death of their mother (Isabelle Huppert) who was a contemporary war photographer. The flashback scenes on her war photography, especially with montages that comment on the potency of professionally hewn images versus the average novice’s snapshots, are compelling. And Huppert herself, the most steely intelligent of French-origin actresses, comes alive in her flashback scenes.

The hitch is we learn she didn’t die on assignment in Afghanistan, rather she had a fatal car crash stateside that might have been a deliberate suicide. Her work is now going to be given a retrospective exhibit at an upscale art gallery, as put on by a colleague (David Strathairn) who is one of those smug types who assumes he is more important than members of the surviving family. Who better to cast for the part than Strathairn, doing one of his variations of the big-headed educated man who thinks he knows better than anybody else? I have an issue with this subplot, though, in that we only come to see Strathairn and Huppert together in flashbacks that are seen, just like any other of the Afghanistan footage, in the most fleeting and cursory way. We have nothing left but to turn back to the Eisenberg and Druid characters, to give the viewer something to latch onto, and hope they open up. They do open up, to each other and Eisenberg with that ex-flame of his in a later encounter, but even the revelations turn out to be all grey layers.

The film’s director is Joachim Trier, a distant relative to the famed Lars von Trier, and he makes his English language film debut. It’s been a peculiarly downtrodden time in recent years for foreign films (here’s a sidetracked lament: when did art films from the international scene begin to perish in quality?), but Joachim’s “Oslo, August 31st” (2012) now so clearly stands as one of the best foreign films of the decade. That film too was a morose character study (morose, only by deceptive instant impression), of a former junkie given one day of reprieve from rehab to attend a job interview that he too easily bungles, only to slip into his old self-destructive routines. Yet that film had immediate tension, and more importantly, it felt like a story that needed to be told.

In contrast, “Louder than Bombs” is a laborious exercise in grief. Say what you will about its sentimentality, but “Ordinary People” stands up today because it compellingly dissected the grief, it used explosive but repentant words shot right from the heart, achieving a psychological cleansing that’s preferable to Joachim’s wallowing in misanthropy.

I am teeming with disappointment yet I have an odd appreciation here. Twenty years ago we got movies that were about actual human beings on a regular basis, and not superheroes. We are immersed in a movie culture currently that is only rarely concerned with portraying actual people. Here are some titles from 1996: “Fargo,” “Breaking the Waves,” “Welcome to the Dollhouse,” “Ridicule,” “Basquiat,” “I Shot Andy Warhol,” “Carried Away.” There are more titles I could mention, and they are all about human beings. Indeed, I recognized human beings in “Louder than Bombs” too. I only wish the film had some real insight with its material.

108 Minutes. Rated R.

DRAMA / ADULT ORIENTATION / WINTER DESPAIR

Film Cousins: “Ordinary People” (1980); “The Ice Storm” (1997); “Snow Angels” (2007); “Oslo, August 31” (2012, Norway).