“It’s insured, so it’s a victimless crime.” – Andy

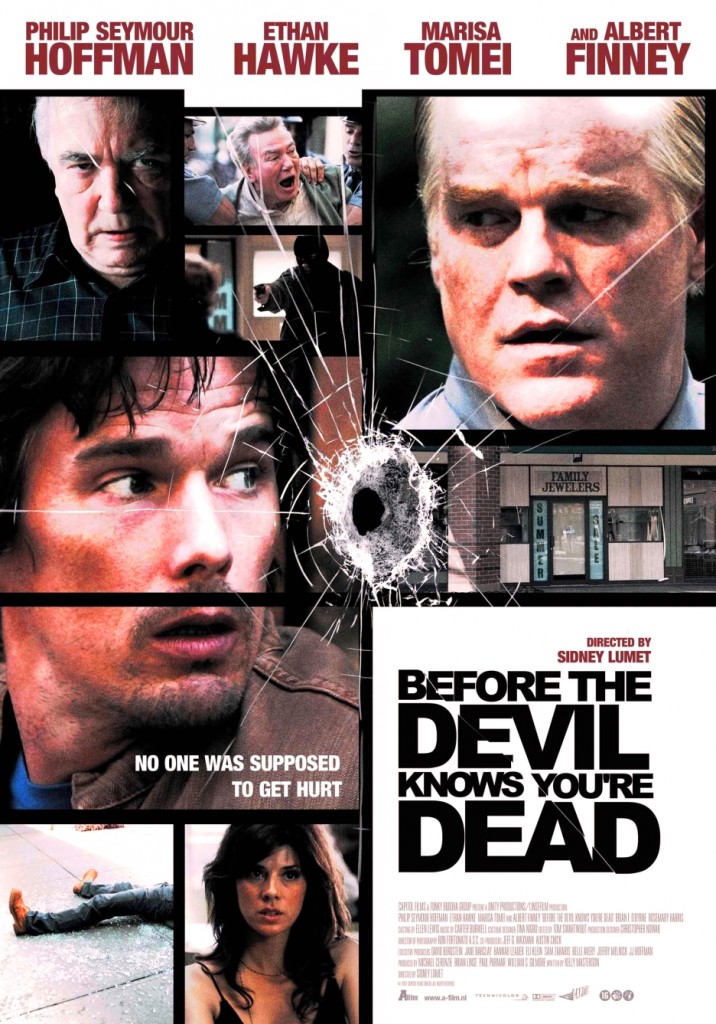

The most anguished, tortured, complex, brilliant performance of Philip Seymour Hoffman’s career. Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead (2007) is the staggering crime drama where two hard luck brothers decide to knock off a mom and pop jewelry store – their own mom and pop’s. Andy Hanson (Hoffman) proclaims, “We don’t want Tiffany’s. We want a Mom and Pop operation, in a busy place, on a Saturday when the week’s takes go in the safe. We both worked there. We know the safe combinations.” Mom is not supposed to be working that Saturday morning. A third outside criminal-for-hire is not supposed to be complicit in the crime. Alas, it does not go according to plan. Bloodshed goes down.

The crime, the prelude and the aftermath get multiple jigsaw-cutting episodes, to see things from each character’s point-of-view. Hank Hanson (Ethan Hawke) is the brother who is supposed to raid his own parent’s store, but with his lack of criminal experience, he has a hot-headed acquaintance (Bryan F. O’Byrne) do the raid. We learn Hank is hard up on paying child support to his ex-wife (Amy Ryan). We learn Hank has trouble paying $130 for his daughter’s field trip. And the obvious: he has a very fragile ego.

Back to Andy. He has a superhot wife (Marisa Tomei), but as cocky as he is, hints tell us that he does not feel deserving of her. The movie opens up with explicit and risqué fornication in Rio, only to be followed by confessions later that they can’t seem to summon that kind of great sex back home. The bulls*** of life can’t compete with a vacation in Rio, is what is said. Regularly back home, Andy embezzles money from his accounting branch at his Manhattan real estate office. Andy pays big money to shoot up heroin in a posh penthouse where privacy and comfort is fundamental. His life is fractured in such secrets.

Hold on, let me observe Hoffman’s acting here. He has the “my life doesn’t add up” monologue at the penthouse. Most actors would look foolish and unconvincing talking to themselves. Hoffman’s snaky businessman shrivels down, he is yearning to be heard, he has bottled anger and shame up for years. You can’t help but go, “Wow, Hoffman knows this character, how does he know him this well?” Hoffman turns purple in several scenes in the film in suppressed rage, compensating his ego by controlling others. When he places his hand on his brother Hank, we might think he is going to squeeze the life out of him. But it’s only to sternly lecture him, and to let him know, You’re not getting up. You’re in my control.

As a result of the robbery, mom (Rosemary Harris) makes it to the hospital but in a catatonic state but will likely not recover from the brain trauma. Charles Hanson (Albert Finney), the father of the clan, makes it his mission to understand why his wife fell victim to this crime. The plot will urgently require from here on out for smart-conniving Andy and bungling-gullible Hank to clean up their tracks and cut off any loose ends. And money, what money? They still need it. When all else has failed, Andy is capable of transitioning from smooth operator to perpetrator of extreme retribution. The only way out is stealing more money.

Of course, Hoffman is the major attraction here, demonstrating that he could take a crime drama character and twist out the tragedy in him. His Andy is cobra-like and calculating, but has feelings of inadequacy. He dreams of starting over, but needs cold hard cash to do it. He has a beautiful wife, but does not know her. He has a brother that looks up to him, but really envies him. Now they have participated in a crime together. Hank is the one that has made lots of mistakes, but is Andy not the one who has ensnared everybody in this plot? Andy tries to not be a ticking time bomb, he does everything in his self-composure not to be that, even the trashing of his own house comes with understatement. But Hoffman, turning purple, is bound to explode.

Hawke, conversely as the nice guy not cut out to be bad, is very good in the movie, too, even if he wears desperation on his sleeve too obviously. Tomei, a pillar of desire as wife Nanette, is a junkie for sexual attention because she’s not good at anything else. Leonardo Cimino as a shady jeweler and Michael Shannon as a blackmailer have crucial scenes that turn the plot as well as show-off their aptitude for character acting.

“Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead” was the final film of Sidney Lumet, who directed with vigorous and merciless mastery at age 83. He was famous for films such as “12 Angry Men” (1957), “Fail-Safe” (1964), “Dog Day Afternoon” (1975), “Network” (1976), “The Verdict” (1982). And he was never properly hailed for such films as “The Hill” (1965) and “Running on Empty” (1988). Lumet believed in extensive script rehearsal during pre-production, so his actors would know the lines inside and out, and so he could also adjust his visual style to suit the actors when it came time to shoot on location. He also had the guile to gut the script: Andy and Hank were friends, not brothers, in the original draft. And he jettisoned Andy’s child from the script. Kelly Masterson’s debut screenplay is not only brilliant, but tightly wound now.

This was the second best film I saw in 2007, only amiss to “No Country for Old Men.” Hoffman was not nominated at the Oscars, nor was the film for anything else, another example proving the Academy has a penchant for incompetently overlooking at least one masterpiece per year. Of course, Hoffman’s Andy is a portrait of shameful human nature spiraling out of control into the vortex of self-destruction, and that kind of heavy stuff – and the gorge of family dysfunction – has some [Academy] viewers steering their eyes away. Anybody who wants a Masterpiece in Modern Dramatic Tragedy, though, which culminates in every last person marred in hurt, needs not to look elsewhere.

117 Minutes. Rated R.

CRIME DRAMA / ADULT ORIENTATION / MASTERPIECE VIEWING

Film Cousins: “Blood Simple” (1985); “Family Business” (1989); “Fargo” (1996); “A Simple Plan” (1998).