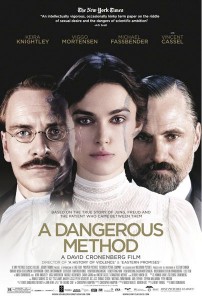

David Cronenberg is at the top of world class directors. You think you know him well enough through his previous work like “The Fly” (1986), “A History of Violence” (2005) or “Eastern Promises” (2007), but as I learned, you don’t. He is even far more intelligent and probing than I had charitably considered. He is as generous a speaking guest as I’ve found. At the recent press junket for his film he tackled every question thoroughly and respectfully, no matter how far off you were from your inherent assumptions. For his latest film “A Dangerous Method,” based on Christopher Hampton’s historical play, he has chosen some unusual yet scrupulous casting: Michael Fassbender as Carl Jung, Keira Knightley as the patient turned psychologist Sabina, and Viggo Mortensen as Sigmund Freud. Cronenberg has never done a period drama, yet this is a case of history that bears influence and impact on modern times today.

Reporting from Los Angeles:

How would you recount your discovery of the film’s source material and meeting with playwright Christopher Hampton?

Cronenberg: I worked very closely with him, but I didn’t see the play. It was playing in London. It never came to North America. But Christopher and I had known each other before.He’s been a director, he’s been on both sides of the camera and so we got along very well. We had the original script to work with, we had a couple of books, and we had all the letters. Then, we worked on a new screenplay, which is basically a combination of all of those things. I think ultimately my main contribution was to decide what should be in the movie and what shouldn’t. The number of people flowing in and out of Freud’s life at the time, there were hundreds of them, his distillation of all of that, down to basically five characters was fantastic.

What if anything was cut out that was close to being in there?

Cronenberg: In his original screenplay, he had Sabina’s mother and father as characters, because they did bring her to the institute, and they did talk to Freud and Jung. You get a bit of that, “my mother told me you said that.” But, I felt we didn’t have screen time to really develop them and I really didn’t want to have them be vestigial characters who then disappeared. It was just normal writer/director kind of stuff. Christopher was on the set quite a lot. He’s very happy with the movie.

Viggo Mortensen almost seems too handsome to play Freud but somehow he pulls it off with honorably? How did you come to the decision of casting him?

Cronenberg: I thought we really needed a not obvious casting for this Freud because this was not your grandfather’s Freud. Which is to say this isn’t the grandfatherly, sick, sternal Freud they think they know.This was a fifty year old, very dynamic, charismatic, leader of a sort of very intense group of people who were doing some revolutionary things… things that were considered very revolutionary and dangerous at the time, very subversive and volatile. This was also a guy who was described in literature of the time as masculine, handsome, charismatic, charming, witty, funny – all things we don’t think of as Freud.

So Viggo, I know his capabilities of course having worked with him and I felt confident he could do it. He didn’t feel confident that he could do it, but that’s very charming of him. And so I basically talked him into it.But when I discussed with him all the things I just talked to you about – what kind of Freud it was… of course he’s got very good taste and he’s very literate and he knew he could tell the writing of Christopher [Hampton] was terrific so eventually he came round and that’s where we were. He’s got a beard of course. We gave him a nose, a false nose. It’s very subtle. You can hardly notice it but that’s not his nose. We gave him brown eyes to make him just to make him a little more Freud like.

How would you say you’ve approached sexual dysfunction this time in comparison to your other past works that have dealt heavily with sexual voracity or aberrance?

Cronenberg: I have no thoughts about sexuality. Seriously, I don’t think about my other movies when I’m making a movie. It’s as though I’ve never made one. Other than I have the craft of having made them. I don’t really try to connect each project with other projects in the way that a critic does. I sometimes have to remind critics that my process and theirs is not the same. These connections. These analyses. They don’t give me anything creatively to help me make this movie – whatever it is that I’m working on.

Certainly sex is a subject. I’m hardly the first. I wish I could take credit but sex and death, the Greeks were doing it 3,000 years ago. These are enduring, continuing concerns of a dramatist. After all George Bernard Shaw said, “Conflict is the essence of drama,” and so we are looking for conflict. Whether it be psychological, it doesn’t have to be physical violence but you don’t have the drama without the conflict.

But as an artist, doesn’t a new project with such strong sexual themes at least remind you of your past films?

Cronenberg: I had friends who pointed out to me something that I had completely forgotten, that the first film I ever made was seven minute short called “Transfer,” and it was about a psychiatrist and a patient. And the patient is complaining that the only relationship that he has ever had that meant anything was his relationship with his psychiatrist, and so he is kind of stalking him and following him around. So, this is kind of coming full circle in that way.

When it comes to “A Dangerous Method,” do you find there are yet other issues about civilization that are besides from sexuality that are worth discussing?

Cronenberg: There are many, many things going on in this movie besides sexuality although they certainly talk about sex a lot, no question about it.But that was an issue for Freud and Jung – his basing a lot of his theory on sexuality. And that was very revolutionary for the time because it was what we would call a very Victorian era in the Austro-Hungarian Empire in middle Europe before the first World War. It was very stable, very controlled. They really felt everyone knew his place and that they achieved an incredible level of European sophistication and civilization. And they felt man had evolved very nicely from animal to super-sophisticated human. Here was Freud saying, ‘That’s all very well and good but underneath the surface – and not very far underneath the surface – are these forces which we have in us still. We have to acknowledge them. One of them is sex, but it’s not always sex. It’s tribal hostility, tribal violence.’ His words were not welcome. People didn’t want to think about that. They didn’t want to hear those things.

And of course, World War I proved he was completely correct. It is hard for us to realize now how shocking the first World War was to idealists at the time who thought that man had really achieved an incredible plateau of civilization. They couldn’t believe that in the center of Europe would be all this tribal barbarity, massacres, genocide, hideous atrocities.We’re a little more cynical about it now because there have been so many wars since then. But at the time it was a real crushing blow to idealists who really thought that there was a chance evolution meant getting better because Charles Darwin didn’t think of evolution as getting better. It meant being different to adapt to your environment. But he wasn’t thinking of it, didn’t conceive of it as something that we were evolving to something better. That we were becoming angelic as opposed to human or anything like that. So all of those things were very fascinating to me. It wasn’t really just sex, obviously.

But it is a large part. Stylistically you include a mirror in all your sex scenes, so Carl and Sabine observe themselves self-voyeuristically while in the act of sex. Can you discuss why you chose this technique?

Cronenberg: They felt they invented a new thing – this psychoanalysis. And the relationship between an analyst and his patient was a brand new relationship that had never existed between humans before. They were experimenting with it. They didn’t really know what the boundaries were.For example when Otto Gross [Vincent Cassell] says, “Well maybe it’s a good thing for us to have sex with our patients. Maybe therapeutically it’s ok?” At that point the ethical boundaries had not been established and the realities of that relationship was were not known. So they were very obsessive about observing themselves. When Freud talked about, wrote The Interpretation of Dreams, the dreams he was talking about were his own because he didn’t have subjects who were divulging to him yet, their own dreams. So he used his own dreams as his subject. Likewise with Sabina, she would – I felt – having plugged in totally to this obsessive psychoanalytic state of mind, would be observing herself. Even while she was having sex, she’d be observing herself – how she felt, what her reaction was, what Jung’s reaction was.Jung is not really enjoying those moments. He’s doing it for her. And he would be observing it to from a sort of clinical distance. So that was really the reason for that choreography. We have no proof that those things actually, specifically happened that way. But I felt, given all the things we know about them that it was reasonable.

Keira Knightley’s character of Sabina goes through a very noticeable change throughout the course of the picture that requires a shift in her facial composure and modification in nervous behavior. Would it be safe to say that you directed her to take chances in her performance?

Cronenberg: She is wonderful. I always thought she was an underrated actress, and that proved to be the case. She is incredibly well prepared, and we discussed, of course, particularly the hysteria. She comes to the clinic suffering from hysteria. She, as we know that she had already been kicked out of a couple of asylums, because she was uncontrollable. She was dysfunctional. She really couldn’t function, and we had to show that. And so it is a question of level: how far do you go with that?

In fact, we were being rather subdued compared with what those patients really went through, and we have records of that. And then in addition, I said to Keira, “You are a woman who is being asked to describe things which are unspeakable to you.” Because a woman—a young woman, she is eighteen—she comes from a wealthy family. To say that I masturbate, because I am sexually aroused by my father is beating me…. This is unspeakable. This is something that was not accepted, and here she is trying to speak it, because she is being asked for the first time. This is Freud’s talking cure. She is being asked for the first time to say these things, these unspeakable things.

It seems that the history of the first examples of the “talking cure” was intriguing to you as a filmmaker?

Cronenberg: You know, in the Burgholzli clinic, was very advanced for its time and it really was like the Garden of Eden for crazy people. They had gardens, they did have orchards. They had forest trails that the patients could walk through, and gazebos for them to look over Lake Zürich and so on. They played music. But the one thing that they did not have was people listening to them. You’re crazy, why would we listen to what you say? Here is Freud saying “No, listen to them, because they will tell you what is wrong with them, and they will tell you how to cure them.” So, here is Sabina for the first time being asked to talk about these fantasies and her sexual reality. And part of her desperately wants to speak it, and wants to confess it. And then part of her feels it is intolerable and vile and repulsive, and she should not say these things, and is trying to pull it back.

So, I said to Keira, ‘I think it really, as is with other cases with these patients, it should all be around your mouth and jaw. You are trying to deform the words so that they are not understandable, and so on. So that was the basis, and Keira – You know you can talk to her about those abstract things, and then she can find a way to embody it. That is her brilliance as an actress. You can see all the way through, that’s always there, even as she becomes a substantial, professional person, much more in control of her life… married, pregnant. There is still that volatility, that fragility underneath the surface.

While Sabina remains a supporting character, the story often makes Jung the protagonist. Would it have been possible to get this movie made had Sabina been the ultimate focus?

Cronenberg: Well, Christopher [Hampton]… his stage play started as a screenplay. It was commissioned by Julia Roberts about 17 years ago, and she was going to play the lead, and it was called “Sabina.”And, of course, for that project Sabina was the main character. Then, that movie did not happen, and he asked for permission to turn it into a play. He began to tell the whole story of everything surrounding Sabina and the context of her life, and it meant that Jung had to become more of a prominent figure in the drama. It is a sort of a ménage à trois, you know. It is true that Jung is really the leading character, certainly in terms of screen time he is. So, that was Christopher’s choice. And when I came to read the play that was really the structure. So, it wasn’t sort of me reshaping it. It was sort of in that mode at that point. Really, it is just a matter of dramatic balance, and structuring a drama. It wasn’t a political thing; you know it wasn’t meant to diminish Sabina’s importance. Obviously, she is still really important to the movie.

What do you think is Freud’s value on psychology in today’s society?

Cronenberg: It is a little bit like Einstein’s theories not being able you be proved until we could send spaceships out into outer space, to test his theories about time and space. It turns out that Freud – also with new technology – that some of his theories have been absolutely confirmed. Modern psychologists like to call it non-consciousness rather than unconscious, so that sort of is a different concept, but it is really sort of basically the same thing.

So, I think we are not done with Freud, or with Jung. As I say, it seems that it has splintered off into many different kinds of therapy. That great invention of Freud’s – the relationship between an analyst and a patient – seems to still have resonance for people. It is sort of a secular version of the confessional; you have someone not judging you – although I guess a priest is more judgmental really – but the idea that, well, as you see with Sabina, a man she doesn’t know is asking her to say these extremely intimate things, and he is not judging her. He is not saying you are wrong… this is bad, you are evil. He is just listening and allowing her to hear herself. So, that still seems to be a valuable thing. We have friends who do that for us sometimes now, but it’s because we all know this kind of analytical procedure, because it has been so much in the zeitgeist for all those years.

The studies of Jung and Freud have somewhat given way to taboo subjects covered on TV programs with Dr. Drew and Dr. Phil in the modern world. Do you think this is a step towards social progress?

Cronenberg: In a way, for better or worse because I hate those shows! I find them totally unbearable and vulgar and ridiculous and hideous– aside from that, in a way these three people – Freud, Jung and Sabina invited that aspect of the 20th century and invented modernity in terms of the relationships that people have.

When you read the letters between Freud and Jung, they feel totally modern. Why do they feel modern? Here were two professional men, highly respective in highly conservative professions writing to each other about bodily fluids and erotic dreams and things that men of that time would never speak those words, especially to other men. When Sabina, their intellectual equal, she spoke about woman’s erotic nature at the same time, the same level, it was also unheard of before. Now, any blogger, whatever, can put it all out there. It was really invented by those people, and how unprecedented it was.

Hollywood has given us a few versions of Freud. Any thoughts in particular about John Huston’s “Freud” (1962)?

Cronenberg: I saw when it came out, believe it or not. That was a long time ago [laughs]. I do remember reading that Huston was the absolute wrong guy to direct that movie because I think he didn’t believe in analysis. He didn’t believe in sex as the driving force of all that was the young Freud played by Montgomery Clift. So I think was very much a classic Hollywood blunder, let’s put it that way. They understood that [sex] was something intense and hot, but they didn’t really get it. Despite that Jean Paul Sartre worked on the script, who really understood Freud, but he wasn’t a screenwriter. Even that element was probably not helpful. At least it was a sort of serious attempt with Freud. There was a BBC miniseries with which was really quite good.