“Our lives are not our own. From womb to tomb, we are bound to others. Past and present. And by each crime and every kindness, we birth our future.”

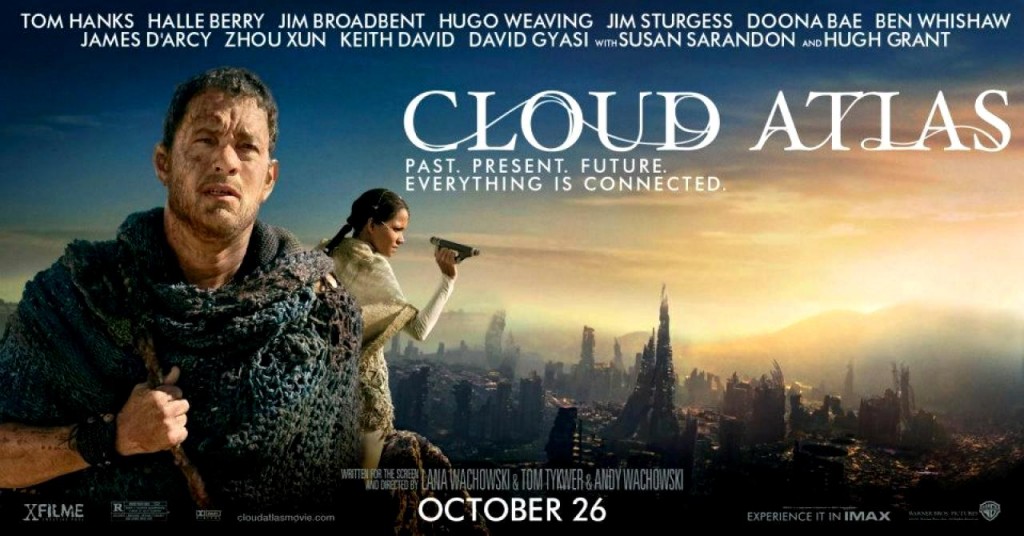

I have never been so wrong about a film in my entire life. Viewing Cloud Atlas again I can see why I had some early initial problems that stemmed doubts. There are six stories that range from 1849 to 2346, and God help me that I couldn’t find instant connections and validity between the cross-cutting of them during the first half hour. What co-directors Andy and Lana Wachowski, and Tom Tykwer do, is plant ideas and let them germinate as the episodes develop. Actors Tom Hanks, Halle Berry, Jim Sturges, Hugo Weaving, Hugh Grant and Doona Bae inhabit multiple characters from different strands of time. The more you see the film, and look deeply, the more touching the performances are. Especially of Hanks, who plays weasels, conflicted geniuses, and a wise old man in the far away future who is the embodiment of inner peace.

Yes, and the more you view “Cloud Atlas,” the more you can see the Hanks of 1849, the Hanks of 2012, and the Hanks of 2346 are all the same person. The thematic idea of reincarnation was always there, but it becomes more fitted once you philosophically link the connections. Hanks is an angry soul over time who finds difficulty in finding inner goodness. Sturges is always destined for privilege but campaigns against intolerance time after time, and in frustration of his fragile intellectual soul, he decides to transform into a great physical fighter for his cause. Weaving is evil in every incarnation, and because he loses, he becomes not another human in the far away future scenes, but an evil specter to do his worst harm.

The 2144 scenes in Neo Seoul, Korea are intended to be the most disturbing. This is a portrait of society degenerated to its worst impulses. It is a world of concrete, lit up by artificial colorful holograms. Bae is a clone whose purpose is of a work around the clock server at a vulgar commercial eatery, and she as well as her contemporary clones are given to shortened lifespans. This is a form of slavery that is linked up with other demonstrations of slavery throughout the film, most obviously the 1849 scenes of white masters and slaves. Most comically, Jim Broadbent is a nebbish book publisher named Timothy Cavendish who ends up captive against his will at an old folks’ home. His predicament inspires a comic movie on his life, which is seen by two clones in the future, who begin – to think more expansively about their existence.

I have seen “Cloud Atlas” at least three times now and I still find certain things confusing or baffling. The feral dialect of the far future is not entirely decipherable. But it has not kept me from trying to follow it a little better with each time I see it. I am only vaguely knowing as to why Berry needs to climb a mountain to reset certain power, but I have found other purpose in those scenes, like, the importance is not so much the turn-on of the generator as much as how necessary her appearance is to change Hanks’ destiny. The episode also takes place “106 Years After the Fall,” and is significant for portraying disparate societies rebuilding on Earth following in an unspecific catastrophe that has cut down on most of the world’s population. It’s inevitable. Every few centuries it’s likely the Earth will undergo vast evolution. This is a film with the ambition to imagine such changes.

I have seen “Cloud Atlas” at least three times now and I still find certain things confusing or baffling. The feral dialect of the far future is not entirely decipherable. But it has not kept me from trying to follow it a little better with each time I see it. I am only vaguely knowing as to why Berry needs to climb a mountain to reset certain power, but I have found other purpose in those scenes, like, the importance is not so much the turn-on of the generator as much as how necessary her appearance is to change Hanks’ destiny. The episode also takes place “106 Years After the Fall,” and is significant for portraying disparate societies rebuilding on Earth following in an unspecific catastrophe that has cut down on most of the world’s population. It’s inevitable. Every few centuries it’s likely the Earth will undergo vast evolution. This is a film with the ambition to imagine such changes.

There is too much action in the film as if to try to meet “Star Wars” type of commercial appeal, or as I first thought, but the film never lingers on gratuitous action. I now find it sensational but in the best way. The action compliments the noble idealizations of its best characters and underlines the inexhaustible evil of its worst characters. The film never puts action “extravaganza” ahead of its ideas.

When the film hits its stride, and it starts making its more significant connections between time, that’s when the film really impacts. More than the action, the renewed spiritual quests are the most sensational aspects of all. I love the music of “Cloud Atlas,” its glorious and triumphant theme by Tykwer, Johnny Klimek and Reinhold Heil. But the film as whole is a symphony of itself. You respond emotionally to things that cannot be described by words.

The still missing lack of description is why “Cloud Atlas” wasn’t hailed as an instant masterpiece, and maybe explains why I was still in a ponderous mode when I first saw it. I had to see it twice. Then three times. Then four. I will see it many more times than that. There is not a boring scene nor a boring shot in the film. The camerawork itself is more expertise than any contemporary Hollywood film today.

I hope the film represents the best of what film can do in the future. Films that are not bound by conventions, by single time periods, by simple themes. Here is one film too vast and beyond the simplistic. “Cloud Atlas” has an unrivaled grandeur and new kind of epic form. Only “The Tree of Life” has reached higher with ambition in recent years. Malick’s film held me faithfully for a couple years. However, I’m currently obsessed with “Cloud Atlas.”

The original novel is by David Mitchell.

172 Minutes. Rated R.

SCI-FI & FANTASY / THINKING MAN’S THRILLER / MASTERPIECE VIEWING

Film Cousins: “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968); “Orlando” (1993); “A.I.” (2001); “The Tree of Life” (2011).