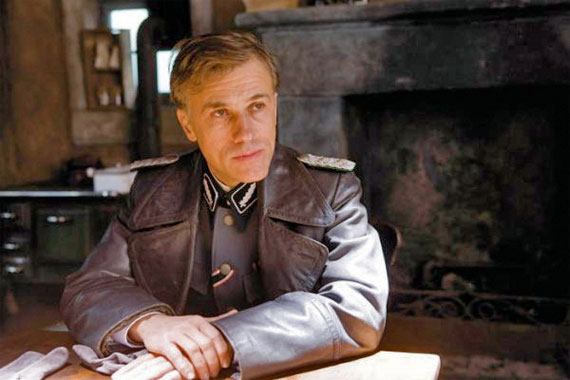

Austrian actor Christoph Waltz as Colonel Hans Landa should go down as one of Quentin Tarantino’s most memorable villains in Inglorious Basterds. The Cannes Film Festival winner for Best Actor, Waltz has dozens and dozens of credits in his filmography yet he is not someone well-known in America at this point. You may recognize him in a small part as a German spy in the James Bond flick “Goldeneye.”

Waltz was recently in Los Angeles to promote the film with the rest of the cast. Carefully observe that the interview is divided into two sections. The second part goes very in-depth into the movie’s mysteries revealing spoilers. Yet the actor’s take on it is so interesting it is not something to cut or leave out. You will definitely want to read it but only after you have seen the movie.

Q: You stole the show.

Waltz: I’m not in the show stealing business.

[LAUGHS]

Q: You got to be a little bit of everything. You got to speak many different languages. You got to be funny. You got to be scary. You got to be romantic. What is it taking on absolutely everything all at once?

Waltz: I disagree entirely. It’s not a little bit of everything. It’s all of that character, and I insist on the unity. That’s what makes it interesting. A little bit of this, a little bit of that sounds very post-modern. Zzzzzzz [SNORING SOUND]. No, no, no, it’s very definitely one line down the road. This character is very, very integrated. That he has many interesting little strands and fibers, sort of mental, intellectual kind of varieties that are really rare in its multitude, that’s a different story. But it’s still one character.

Q: Before casting, what did Quentin Tarantino know about you? Or, how did he discover you?

Waltz: I don’t think he knew anything about me. It was through a casting agent in Berlin.

Q: What was your first meeting with him like?

Waltz: It was very traditional casting with the casting agent in Berlin. I was one of the lucky ones. It was kind of late in the casting process. First of all, they sent me the script. That is not something that’s usually done anymore, unfortunately, to my regret. Because usually you get like a page and a half with a few lines, and then what? You have a page and a half with a few lines, but you don’t have a part! Anyway, Quentin sends you the whole script, so you know what the story is when you go to meet him. And, that’s a different meeting when you’re talking about the film. And, [it’s] not about me as a person, what can I do, or how can I sell myself. That’s boring! So, it was really terribly interesting, to be able to talk with the author of this fantastic script about this fantastic script. We didn’t have to waste our time with [whether] I could do it.

Q: How long did you spend cultivating this character? Is it over a period of months?

Waltz: I had two months to study the script. I don’t think in terms of cultivating. Basically, that’s what it is. You can’t avoid it. You read it, and the thing starts to ferment in a way, subconsciously, consciously, whatever. So actually, in the literal sense of the word, that is a cultivation. But, I don’t aim at cultivation. I just try to find out what is in front of me on the page.

Q: Was it entirely organic, or were there any exterior references or influences that helped you access this character?

Waltz: Actually, [when] I want him [Quentin] to suggest references, because this man has an encyclopedic knowledge of film, you can say, yeah, can you show me like an analog character in a Hong Kong movie, and he would have it like that! So, he asked me, “Do you want me to suggest anything?” And, I said, “No, the script is enough! It’s plenty, and it’s probably more than I can digest, because there is so much in it!” I had about two months because I was cast about two months before we started. Two and one-half months. So, I was busy reading the script. That’s what I did.

Q: The rest of the cast is talking about how much the set inspired them. How Quentin just loved making the movie. Did you draw any inspiration from that, and, if so, what was it? Or did it help you as an actor and did it inspire you?

Waltz: Of course it helps you to be in a beautiful room. It always helps. That’s the profession of the production designer to actually make this room perfect for the situation. But, it’s all in the interest of what the director intends to do. Or, what the author intends to say. And, even the director works in the interest of the story. So, in this case, the lucky circumstances were that the author and the director are the same person. So, you could really 100 percent rely on the vision. In the course of the years, you get accustomed to the fact that it’s going to be very impressive, and costumes can be good or bad, but still it feels good. It’s nice. But, I don’t over-emphasize these things. I don’t attribute value [to them]. That is bordering on the esoteric. I don’t do that.

Q: How was working with Quentin and Brad Pitt? What did you learn from it?

Waltz: Well, they are, you know, master craftsmen. And, you know what? I consider myself a master craftsman too. That doesn’t say anything about the level of the mastership, you know, but like a black belt. It’s more fun to work with masters. I don’t consider myself a seventh dan [pronounced “dawn,” a degree of martial arts belt]. I consider Quentin a seventh dan. And, Brad certainly has high ranking in that respect. So, no, in all seriousness, these people know exactly what they’re doing. They’re true artists, masters at what they do. There’s no greater joy for me. I love working, but I love working properly. I don’t like showing off, or pretending. It’s fantastic work, but you have to do it.

Q: Can you just talk a little bit about the rehearsal process, what it was like to be manipulated by Quentin?

Waltz: You’re not being manipulated, not at all, and that’s one of Quentin’s great qualities. He does not manipulate, he inspires. He operates on a level of energy that has no comparison. And, he inspires. He establishes this stream, this flow of awareness for his vision and his story. And, all you really need to do is bury self-interest.

Q: He inspires something? He gives you an image or something that. . .?

Waltz: He does not instruct. He does not teach. There’s nothing didactic about his approach whatsoever. He inspires you. In a way, it seems to be a little like magic. He inspires you to the degree where you end up doing, with full conviction, exactly what he needs for his movie.

Q: What kind of impact has the Cannes Film Festival meant for you personally and professionally?

Waltz: It turned everything on its head. Not so much personally, because personally I’ve been doing this for quite some time. I would recommend for every actor to wait 30 years until something like that happens. Because, I think as a 25-year-old, I could not handle it. You have to fly off the handle somehow sooner or later. Not Brad [Pitt], for example. He really stuck to his guns. You know, you have all these stories about new shooting stars who end up in rehab. There are psychological consequences, absolutely. So, I’m lucky that I’m 50 [when this acclaim happened].

Q: How are you adjusting to all the international interest in you? Because I know you were huge in Europe, but now I hear everyone is interested in you.

Waltz: I said this after Cannes. 10 flashbulbs bother you; 10,000 are fantastic!

PART II:

[SPOILER ALERT from this point forward…]

Q: What was your first response when you read the script and saw how it takes liberties with history? Was it surprising, disturbing, fun?

Waltz: Explain to me how he’s taking liberties with history? How do you do that? How do you actually go about “taking liberties with history?” Are we worried because Quentin offers a new perspective on how to view it? Are we worried that certain things then would miraculously disappear? No, we’re not! He doesn’t take liberties. He takes artistic liberties in his narrative. That’s his duty as an artist. I’m not shocked about this. . . . I’m not even irritated. I’m not even sure if I’d be irritated if I was an historian, because historians know history even better. I’ve been asked before, are you worried about the reaction in Germany or in Austria about this rather unusual outcome of the story. And, I said, Why would I be worried about, what reason is there to worry? Do you think Germans or Austrians want their ‘dear Adolph’…

This is our fourth generation after the war. These people don’t have a feeling of guilt. That doesn’t mean they don’t have a feeling of responsibility. And, that’s the interesting aspect. So everybody in Germany today has had this fantasy about this outcome. And, you know what? In Berlin, at the screening, as this moment approached [when the spies were trying to kill Hitler and the German high command], everybody was relaxed. We’ll see in a second. A sigh of relief went through the room [when Hitler was killed]! And, they were cheering. Of course, in Germany, the desire to see this is infinitely greater than anywhere else. This reaction really materialized. And, so there! Am I worried? No.

Q: As an Austrian, what was it like when you found out that you were the one who was going to participate in Hitler’s downfall?

Waltz: To tell you the truth, I didn’t find that out as an Austrian, I found that out as an actor who just needs to find out what he’s supposed to do. There’s no way of finding stuff like that out as an Austrian. The connotations kind of go over the top there a little bit. It’s along the same lines. It’s great. I’m part of this whole big, fantastic story. And, my idea about what I do is to get out of the way of the story. Get out of the way of the character. That’s not that easy to do, you know, because of course one has the ambition to excel, one has the ambition to impress. The job is to open the way for what’s on the page, especially if you have such a fantastic script.

Q: Do you find that, over the course of your career, do you find personally that you learn a lot from the characters you play?

Waltz: Absolutely. And, that’s what you do as an audience too. That’s why you go and see it. Because you can actually participate in [these] experiences, the consequences of which you do not have to bear. It is proxy experience in a way, but it doesn’t mean the experience isn’t real. So, that’s where actually the responsibility of filmmakers comes in. And, that responsibility is sometimes neglected. People, audiences identify, and they identify for this reason. They want to have the experience without actually having to stick it through in real life. As an actor playing a part, you’re even one step closer to that, because you kind of get to do it, you know, without really going through, or having to, as I said, bear the consequences that you would have to bear with having it in real life, so to say. So, it’s a very interesting subject, these layers of reality, because viewing a movie is a reality. The movie is a reality. For me as an actor, playing a part is a reality. That doesn’t mean that it’s the same reality as if it happened in the so-called real life or real world. In that respect, we can come back to the historical question. Historically, he’s taking liberties [but] no he’s taking liberty with his cinematic reality, but that’s his job. If you remember that one shot in the movie where the light beam from the projection booth is shot from an angle. You see the projection booth with the two windows and the projection beam is going out to the screen from the left window, and all of a sudden, it changes to the right window. I find that a beautiful metaphor for this whole process. It changes the light that’s being shed. It changes places. And, the story continues, but now you see it from a different angle. That’s what the historic process is.

Q: Were you surprised by your character’s arrival at that negotiation scene at the end as an actor? I mean, it wowed me that he would just dissolve everything and say, I’m going to create a union with your people. . . . When you read that what was your response and the actual realization of it on film? How did you justify that for your character?

Waltz: You could view that as a treaty. He was just an opportunist who switches sides. But, you could also view it as a shift of the light beam, you know. I take it seriously what he says when he says, “I’m a detective, a very good detective. Finding people is my specialty.” Sure, you know, the employer in this case was dubious, but then he doesn’t apply judgment. He doesn’t apply moral categories. He could, but he chooses not to.

Q: So his rat theory [when Col. Landa compares Germans to hawks and Jews to rats] is just a means of negotiation?

Waltz: Yes, in a way. But, I was quite offended when a German journalist wrote that this is a man who likens Jews to rats without the blink of an eye. But, I thought, poor idiot, he didn’t get it. Because [Col. Landa] says yeah the German could be a hawk and the Jew could be a rat, and the Nazi propaganda says the same thing. “But,” Col. Landa says, “where our conclusions differ, I do not consider the comparison to be an insult.” That really is a clue for the whole part [of Landa]. Others apply moral connotations, and derogatory and racist and dangerous [connotations], but he, Landa, says, “I look at the rat. The rat has fantastic qualities, and the Jews have fantastic qualities.” He’s in full appreciation of what this whole layer of reality entails. That makes it infinitely more interesting than saying, “Well, he calls Jews rats and Germans hawks.” This is fantastic playwriting, on the highest level.

Q: They’re hiding, they’re burrowing, they’re nesting underneath the house [referring to the Jewish family hiding under floorboards in the movie’s opening scene].

Waltz: Yes, they understand how to survive under terrible circumstances. They still know to survive. [Col. Landa] says that, because he appreciates what immense feats human beings are capable of.

Q: Do you mean Shosanna [the family member who gets away]?

Waltz: Maybe. What would have happened if he had shot her [when she ran away in the opening scene of the movie]?

Q: Yeah, I was wondering what his motivation was. If it was actually physical because she was out of range? Or if it was a decision? It definitely seems like a decision.

Waltz: That’s a good guess. What would have happened had he shot her?

Q: There wouldn’t have been a movie.

Waltz: Yeah, absolutely! Why not?

Q: Because there’s no drama for him [Landa] in it.

Waltz: There you go! Exactly.

Q: He’s not doing it for intrigue.

Waltz: For testing, if you want.

Q: Is there a certain level of respect for her, because she got out that far?

Waltz: Yes, possibly. Absolutely, absolutely. And, admiration for [her] guts, and to prove his theory.