If you were going to ask me who were the Best Director winners of the past 50 years, I could name 48 of them. I could never name the best director winner of <em>The Artist</em> without looking up the correct spelling, which I need help with every time. Paging his name… Anyway, I also thought at the time—gut feeling—that Michel Hazanavicius was going to flame out quickly and never make another movie that would make a blip on the radar (I was right!). The other Best Director winner I’ll never be able to name are the co-directors pair for “Everything Everywhere All At Once” for I don’t care to ever remember their names, other than to have a cursory recall of their names so if they shall pop up on a marquee I can gladly avoid — like the plague — anything else they ever make.

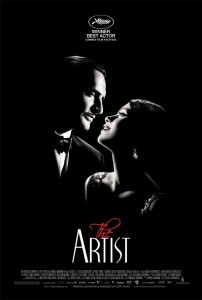

<em>The Artist</em>, in glistening black and white, is a tribute to a bygone era when actors relied on expressionism or good tap-dancing skills to scale their fame in Hollywood. Handsome lug and dashing star George Valentin (Jean Dujardin) is the reigning screen idol of 1927 who does action and can dance, and has the world at his feet. Or so it seems. He is warned by many, from the studio chief (John Goodman) to his own dour wife (Penelope Ann Miller), that he as to learn how to translate into a talkie movie star. The filmmaker’s bogged down message is that Valentin’s pride gets in the way of preserving his career.

In the movie within the movie that opens the picture (very meta), he has electrodes connected to his skull while some euro-trash villains command him to talk and give away his secrets. But it’s just another Valentin movie. When he exits the premiere to get his photo taken by paparazzi, a very forward ingénue named Peppy Miller (Bérénice Bejo) kisses him just to steal the spotlight. <em>“Who’s That Girl?!!”</em> Well, it’s the lady who rises to fame with rocketed fan-following, in contrast with Valenin’s descent once the rise of 1929 talkies takes hold of the public’s interest. But really, who is Bejo? She’s incredible! She winks at the camera with self-aware buoyancy, and says everything always with impeccable timing (through the aid of title cards, of course).

This novelty of an entertainment has fleeting gorgeousness. But the Valentin character hits the bricks too early, and the movie goes on for a damn while saying the same thing about him bottoming out; only Peppy Miller is a levity to the slump of the storytelling. Though it’s true that I really love how the Bernard Herrmann “Vertigo” theme is cribbed, it’s well used, even lusciously used.

Anyway, this picture is just fine, and nice for a low-key night. Though I’ll admit I couldn’t help but have some kind of resentment for it as I revisited it. Not just winning the Best Picture Oscar. But doing that feat in 2011, one of the greatest years in film history, where you had at least twenty greater pictures that year. Outstanding pictures. Extraordinary pictures. Everlasting pictures. <em>The Artist</em> is not one of them. Did the body of the Academy not see more than two pictures that year? Malick. Chang-dong. [Bennett] Miller. McQueen. Ramsay. Von Trier. Cronenberg. Payne. Those are goddamn names worth reckoning with.

I expected an awful movie, what I did not expect is that it would at least have visual panache. Maybe too much so, since it thrusts past coherence way too often just so it could have a romp of a way with itself.

How do you spell this thing? <em>Mortdecai</em> has maybe the worst title in movie history next to “Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Brussels” – that one is the worst, because even if you are beholden to its’ artistic statement, I dare you to remember the name of it full title without making mistakes. Hold on, though, I admit, how could you possibly want to see a Johnny Depp movie with this kind of title? This kind of Frenchy-name title is daring you not to see it.

Yet I saw it. Handlebar mustached Depp, like a well-groomed Austin Powers or Inspector Clouseau except kind of bad/naughty, is an art dealer who is in a whole of naughty trouble with authorities.

Instead of recounting the plot for you, I’d rather just tell you that the movie is too aggressively in a mad dog rush to go from one romp and complication to the next, in a way that is poorly told, and told in too much mess of a plot to get it down straight.

I was surprised, however, by how sexy and fetching Olivia Munn was as a naughty bad girl. Munn tries to get our hero to dance at a swank party, and I didn’t care if what’s his name danced, I just didn’t want her to stop dancing. And that white dress! Who knew Munn could look so good in white! I’m gonna go look up her other movies after I’m done writing this.

Gwenyth Paltrow looks flummoxed as what’s his name’s wife; Paul Bettany looks toasty as what’s his name’s right-hand man who shags babes a lot on the side; Ewan McGregor looks swaggering as an (Interpol?) agent.

Take note, I was laughing hysterically, for unconventional reasons, when I stepped back with bewonderment in how so many people – I’m talking the set dressers, the grips, the costume designers – worked so, so, so, so damn hard on this movie! And for what gain?! Really, a lot of people worked fiercely hard on this movie, um, called, <em>Mortd</em> – dammit, I can’t spell it unless I look it up again.

Taking a page from 1935’s “Bride of Frankenstein,” two incredibly unstylish geeks (Anthony Michael Hall as Gary, Ilan Mitchell-Smith as Wyatt) build a woman via a computer program and she comes out as the rockin’ and bitchin’ Kelly LeBrock. If you were alive in the 1980’s, you’d remember LeBrock as ethereal, statuesque, sensual, incomparable.

Irony is that once these boys have their dream woman of their own they are too shy to do anything with her. LeBrock has to insist on Wyatt to kiss her, because it’s really a lesson to him that he needs to loosen up. As for Gary, he uses this dream woman to make his school crush (Suzanne Snyder) jealous and maybe she will now want him. Same goes for Wyatt who likes another girl (Judie Aronson).

Part of the reason that <em>Weird Science</em> is as good as it is depended on John Hughes not treating it with textbook craft to make it look like any other high school movie. The funniest bits are when it is at its most surreal, at its most bonkers. This is an unpretentious work where Hughes the author says something compact about social acceptance and mature growth, and does it with briskness.

A big party, some outrageous adversaries of the “Road Warrior” and “Hills Have Eyes” variety, some brainwashing of parents, some freezing of grandparents, a tornado storm, are part of the lunacy. Hughes let go of the tidy moral messages of his previous work and just let his imagination run amok.

Robert Downey Jr. immediately impressive playing a jerk and bully who comes to envy Gary and Wyatt; Bill Paxton mercilessly obnoxious as Chet who gets zapped into becoming some kind of Jabba the Hut in what is a howlingly funny comeuppance.

Front and center, Hall and Mitchell-Smith are geek geniuses and they are given a suggested maturity arc. As welcome as everything is, the film would have nonetheless been better if they had transformed into cock of the walk ladykillers or taught to be worldly connoisseurs of travel, finance, sex, and the playboy life. I just still see them at the end as knuckleheads.

But LeBrock, oh my god, she is womanly, maybe even motherly, in her wisdom. Yet sophisticated and chic in that British empress way, a funny and sexy tease, and even a little mindbending the way she treats stupid parents.’

What could the most gruesome and tasteless low-budget horror flick of 1986 look like? It might look like <em>Crawlspace</em>, which has another outlandish performance by uber-weirdo Klaus Kinski—he’s a serial killer of women who rent his apartment house. Simple reason I could never get into it is that the duct spaces look like movie sets as does everything in the entire movie looks artificial. The women victims, uninteresting.

Yeah, I’m not falling for it.

In 1932 small-town Alabama, Jem and Scout are the two children who watch their dignified father Atticus Finch (Gregory Peck) get called forth to defend black man Tom Robinson (Brock Peters) who has been accused of rape. Nary a scene of the black man carrying on with his business before the incident, or a shot of him being arrested, or a clip of him being mistreated in jail, etc. When we meet Tom’s wife Helen (Kim Hamilton) late in the picture, she doesn’t even have a speaking line.

The movie fiddles about the first hour with the children playing like unfettered innocents, spying on their neighbors’ peculiarities, learning tidy moral lessons from their father, confronting bigotry at school, and being spooked by the outcast Boo Radley (Robert Duvall, first screen appearance, who is like the big stalky idiot from “Straw Dogs” or the main idiot from “Of Mice and Men”). Before the trial, Atticus has to guard the jailhouse from a mob of anti-black hicks but it is Scout whose innocent way with words whom is able to scare off the hicks and send ’em home… yeah, not sure about that one. We are nearly at the 70-minute mark until we reach the courtroom, the crux of the movie.

Come on, really, why are we waiting that long to arrive at this point?

Peck is universally remembered for being righteous and splendid in the courtroom with his upstanding saintliness and comely speeches. What I had forgotten is how easy his case is, where he just has to point out to the jury the dexterity of right hands versus left hands; i.e., the victim had been struck with a left hand, but Tom’s left hand is non-functional. Plus, there’s no medical evidence. Nada. Zero, Zilch.

Then we’re struck with a brutal truth: That an all-white jury in 1932 is too stupid (and too prejudicial) to pare the facts down to come up with a reasonable doubt.

It’s not like I’ve spent my life thinking about this movie to death, I’d have to go back to the 20th century to try to remember why I once respected this movie (before this rewatch I just didn’t have the remembrance for it). <em>To Kill a Mockingbird</em> certainly doesn’t go down in the way I thought it would. So, some plot surprises.

But I now agree with some influential critics, including Roger Ebert, that the black people in this movie are used as props so that it can serve as a portrait of the Noble White Savior. Per my addition, what we have here is an agitprop of Fine-Acting White Persons versus Slobbering Racist White Persons, with black people relegated as a plot device. Hence, big point coming: I think I was socially programmed to “like” and “revere” this movie at a young age rather than question it.

We get to the all-distracting boogeyman and fake boogeyman intrusion at the climax, with the reveal of who Boo Radley really is coming to surface. So there’s that. But… We don’t get a real final scene with Tom Robinson! It all boils down to discussion about Tom, with him off-screen.

I’m going to backpedal here: It’s funny, for an hour I was thinking to myself Tom Robinson has all the depth of a pork chop because he’s not really dealt with. But he talks on the stand, finally, and we get to know his vulnerability and his fear—for a bit. Tom has the posture of humility in the last shot we see of him. <em>But he don’t matter, he not quite a man but just a plot device</em>, I say. What matters is that Atticus Finch is older and wiser by the end, and that his children learn to be tolerant towards all God’s meek creatures.

I take another swipe at this movie: Director Robert Mulligan and screenwriter Horton Foote piously treat black people as meek creatures. I have no opinion on author Harper Lee because I read her book so long ago I can no longer form an impartial criticism of it. But I tell you the truth, this movie does not have me pining to re-read it.

I don’t see it as an honorable landmark but instead a cultural poison which took a big subject of injustice and continued to minimize black people, not exalt their voices (a novel like Richard Wright’s “Native Son,” on the contrary, is so enlightening that it is a masterpiece of a book). <em>To Kill a Mockingbird</em> is such a cloying disappointment to me that it has me thinking that something like “Mississippi Burning” (1988) is so way, way better than I last gave it credit for. And I always thought “Rosewood” (1997) was John Singleton’s best picture. As for movies like “The Help” (2011) or “Green Book” (2018), I happen to think they are 3-star pictures (this is against the grain of many, I know), because as rose-tinted as they are they still gave subjective POV to black people and at least circumvented what 60’s racism was really rooted in.

Last riddle: So what was a movie made in the 1960’s that was honestly and subjectively about black experience? That would be Michael Roemer’s “Nothing But a Man” (1964) which ought to be way more famous than this Atticus Finch fable.

This silent movie about the silent movie era is luscious. The Artist, in glistening black and white, is a tribute to a bygone era when actors relied on expressionism or good tap-dancing skills to scale fame in Hollywood. Handsome lug George Valentin (Jean Dujardin) is the reigning screen idol of 1927 who does action and can dance, and has the world at his feet. Or so it seems. He is warned by many, from the studio chief (John Goodman) to his own dour wife (Penelope Ann Miller), that he has to learn how to translate into a talkie movie star. The filmmaker’s bogged down message is that Valentin’s pride gets in the way of preserving his career.

In the movie within the movie that opens the picture (very meta), he has electrodes connected to his skull while some euro-trash villains command him to “talk” and give away his secrets. But it’s just another Valentin movie. When he exits the premiere to get his photo taken by paparazzi, a very forward ingénue named Peppy Miller (Bérénice Bejo) kisses him just to steal the spotlight. “Who’s that Girl?!” Well it’s the lady who rises to fame with rocketed fan-following, in contrast with Valentin’s career descent once the rise of 1929 talkies take hold of the public’s interest.

But really who is that girl, I mean, Bérénice Bejo? She’s incredible! She winks the camera with self-aware buoyancy, and she says everything always with impeccable timing (through title cards, of course). “The Artist” is picking up lots of hype during this awards-bait season, certainly riding on the Best Actor award for Jujardin at the Cannes Film Festival earlier this year. Why did he win? For charisma, mostly. Crossed-fired with depreciating self-pity that he injects into his character during the film’s second half.

His fame forgotten and money floundered after the stock market crash, Valentin sells and sells until he’s got nothing left but the old film canister of his favorite work. But one person has never forgotten him, and that’s Peppy. You won’t get a steamy love scene between them – the 1920’s had their entertainment limits – but the director, Michel Hazanavicius, has a dandy old time underlining the finer gestures that score their affection for each other.

“The Artist” wants to be greatly touching, and for moviegoer wet blankets, it will be. But I appreciated it most for its aesthetics. It has a similar look, as well as shared themes, with one of the last great silent films, “Pandora’s Box” (1928). Except it’s got a cleaner, less scratchy look, since film celluloid from that era could not be faultlessly preserved. And for the heck of it, Bernard Herrmann’s music score from “Vertigo” (1958) is cribbed to magnificent humming effect.

Co-stars include Malcolm McDowell, Miss Pyle, and James Cromwell as the driver. And it’s got a great mimicking dog that loves to play dead to hysterical effect. And at long last, the final words are priceless. Until then, “The Artist” coasts along with the assistance of sound effects, music and actors’ body language.

100 Minutes. Rated PG-13.

FOREIGN FILM / SILENT FILM / WINTER TALE

Film Cousins: “Sherlock Jr.” (1924); “Pandora’s Box” (1928, Germany); “Singin’ in the Rain” (1952); “Silent Movie” (1978).