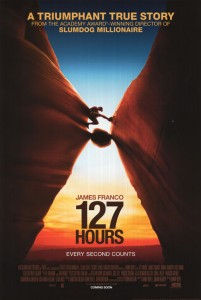

Riveting survival story is unflinchingly graphic. 127 Hours sounds like the most static of all film ideas, but it never is static and instead is relentlessly visually inventive. James Franco (“Pineapple Express”) is momentous as Aron Ralston, the 27-year old hiking and exploration jock who went out on his own in the Canyonlands National Park in Utah and literally got his arm stuck between a rock and a hard place, sandwiched in, with legs dangling. Until then, the endless miles of natural landscape splendor is awesome. After the crucial turning point, the film still has flights of imagination and dreamlike liberation. Pain enthusiasts and realist enthusiasts will be drawn in, and suckers for hardcore drama will be pinned to their seats. The story of how Aron dispensed resources and self-monitored his temper to transcend an impossible situation is an intellectual and emotional adrenaline fix.

Danny Boyle directed two of my favorite films in recent years, the brainy sci-fi “Sunshine” and the Oscar-winning “Slumdog Millionaire” about an Indian orphan’s rise to triumph. With “127 Hours” he uses various color stock and employs the best use of split-screen photography since, say, Brian DePalma’s “Carrie” (1976). While keeping an eye on Aron, the film utilizes split-screen in order to get the images inside his head, as if we were entering his sub-conscious. With this new film, Boyle proves he is really on a roll. Again, he has the proven ability to tackle drama with stylized action dynamics. Although it must be said that “127 Hours” might not be meant for everybody due to its explicitly realistic detail of body injury.

Opening with rapid-fire action, Aron showers and packs up and hits the road in the wee hours of the morning. Upon his arrival at dawn, he shoots out the back of his truck on his bicycle and soon takes a nasty spill, that, of course, doesn’t faze him one bit. While on his hike, he meets up with two attractive girls (Amber Tamblyn and Kate Mara) who are just doin’ fine, if a little lost. But Aron, within bounds of politeness, really begs to be their new tour guide. It’s his superstar time to show off.

The conventional route will show the girls the same gorge undertow and destination cove that every other hiker has ever seen. But Aron wants to show them a special way that is off the map. He leads them to a narrow crevasse that would be safer if they were all wearing suction-cups. He urges to girls to let go and fall at the end point, a drop that leads to an underground hot springs. Aron is so much a daredevil that he doesn’t realize that it just might be dangerous to the girls he has dragged along.

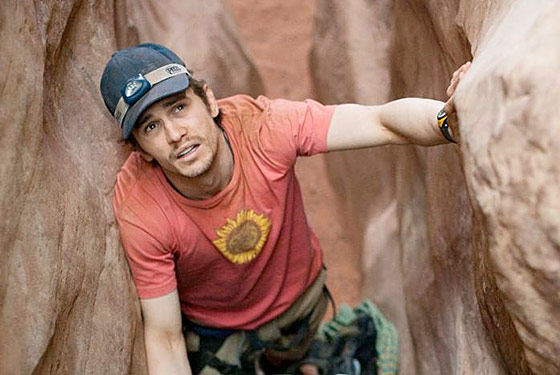

This is not the pivotal incident that leads to body trap, instead, it establishes the reckless nature of Aron. The girls invite him to a party to be held the following night in town (they still think he’s cute), and Aron graciously appreciates the invitation while not fully committing. Aron, now off on his own, like a primordial hunter, mad dashes across and through some jagged terrain with chasms under his feet below. Without caution, he steps on a rock that drops in a blink of an eye, his body falling over it, into a gorge with a descending boulder that pins his arm to the wall. His feet dangle, but can find foot support if he stretches them apart. His backpack is intact full of survival arsenal of descending uselessness, but when he puts the parts together he is able to manufacture an indefinite escape plan.

The food and water rations are low, and with only one free arm, he is prone to make mistakes by spilling precious crumbs and droplets. On his first night, he closes his eyes at 12:17 a.m. to get much needed sleep and jars awake after wearying agony to see that only a few minutes have passed. In the morning he gets his sight on thirty-minute sunshine that combs his body’s lower half. If he listens carefully, he can tell that there is absolutely no one to yell to for help. The more time he spends there, the more fated to hallucinations he undergoes. Persuasively, he tries to put a lid on his entrancing delusions. According to other nature survivors that have been isolated or stranded before him, Aron is bothered by songs that won’t leave his head.

The food and water rations are low, and with only one free arm, he is prone to make mistakes by spilling precious crumbs and droplets. On his first night, he closes his eyes at 12:17 a.m. to get much needed sleep and jars awake after wearying agony to see that only a few minutes have passed. In the morning he gets his sight on thirty-minute sunshine that combs his body’s lower half. If he listens carefully, he can tell that there is absolutely no one to yell to for help. The more time he spends there, the more fated to hallucinations he undergoes. Persuasively, he tries to put a lid on his entrancing delusions. According to other nature survivors that have been isolated or stranded before him, Aron is bothered by songs that won’t leave his head.

Aron’s tiring work on a conventional escape plan proves futile, but while in process, we come to see that while it is not working in freeing him, he is at least making the situation more bearable. Just like what really happened, Aron pours out his thoughts onto his mini- camcorder first as a diary and then as a testament. He makes apologies to his mother for not returning her calls and explains why it is a wrongful part of his “hero” nature to never tell anyone where he was going. He is the grandiose loner-adventurer who never needed assistance until now. As he continues to go through hunger and numbness, we finally arrive along with Aron the drastic measures he must choose if he wants to survive, and the option is far from pretty. The option is a salute to pragmatism over pride.

Some viewers might think that Aron made an arrogant mistake that is too painful to watch. Would it help for me to tell you that the misfortune makes Aron more cognizant to the meaning of personal attachments and teamwork? Perhaps it is worth saying, even in the face of mother nature’s traps, the world still needs guys like Aron to trek the world where no man has gone before, so he can leave caution to us behind. “127 Hours” is a detailed ordeal that can be riveting if you are one rapt by how the smallest tools, literal and figurative, can be orchestrated towards extending survival. Extending long enough to allow a person, in pain, to look deep within himself to know what earth, enlightenment and personal identity is all about.

Boyle drapes a fever over you that you can’t kick, and when it’s over, you might find yourself walking out swinging your arms and legs in appreciation of the gifts you have.

93 minutes. Rated R.

DARK DRAMA / SUSPENSE-THRILLER / WIDE AWAKE WEEKEND

Film Cousin: “K2” (1991); “Alive” 1993); “Touching the Void” (2003); “Gerry” (2003).